Researchers studying tigers and lions at the Wildlife Conservation Society’s (WCS) Bronx Zoo in New York City have studied the first known cases in the United States of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) being naturally transmitted from humans to animals.

The report is the first to document SARS-CoV-2 infection among non-domestic felids, say SusanBartlett (Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx) and colleagues.

The team recommends that personal protective equipment (PPE) should be used to reduce the risk of coronaviruses being transmitted to Felidae and other vulnerable species.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

Siberian "Amur" tiger in the Bronx Zoo. Image Credit: Vladimir Korostyshevskiy / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 pandemic

Following the first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China, late last year, the causative agent, SARS-CoV-2, rapidly spread across the globe and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.

In the United States, the first cases of infection were reported in late January in Washington State, and in New York City, the first case was reported on February 29. In March, New York City became the epicenter for the disease in the United States, with approximately 425,000 cases reported as of August 17.

Tigers and lions at Bronx Zoo in the city became infected

On March 27, a Malayan tiger (T1) at Bronx Zoo became ill, with symptoms including a cough, wheezing, and loss of appetite. Over the following week, another Malayan tiger (T2), two Amur tigers (T3 and T4) and three African lions (L1, L2, and L3) were also presumed to be infected, based on respiratory symptoms that were similar to those seen in T1, evidence of fecal viral RNA shedding and isolation of SARS-CoV-2 from the feces of T3 and L3.

After immobilizing the index case (T1) and examining the animal’s tracheal wash fluid, necrotic cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 RNA were identified, confirming that the virus had caused tissue damage.

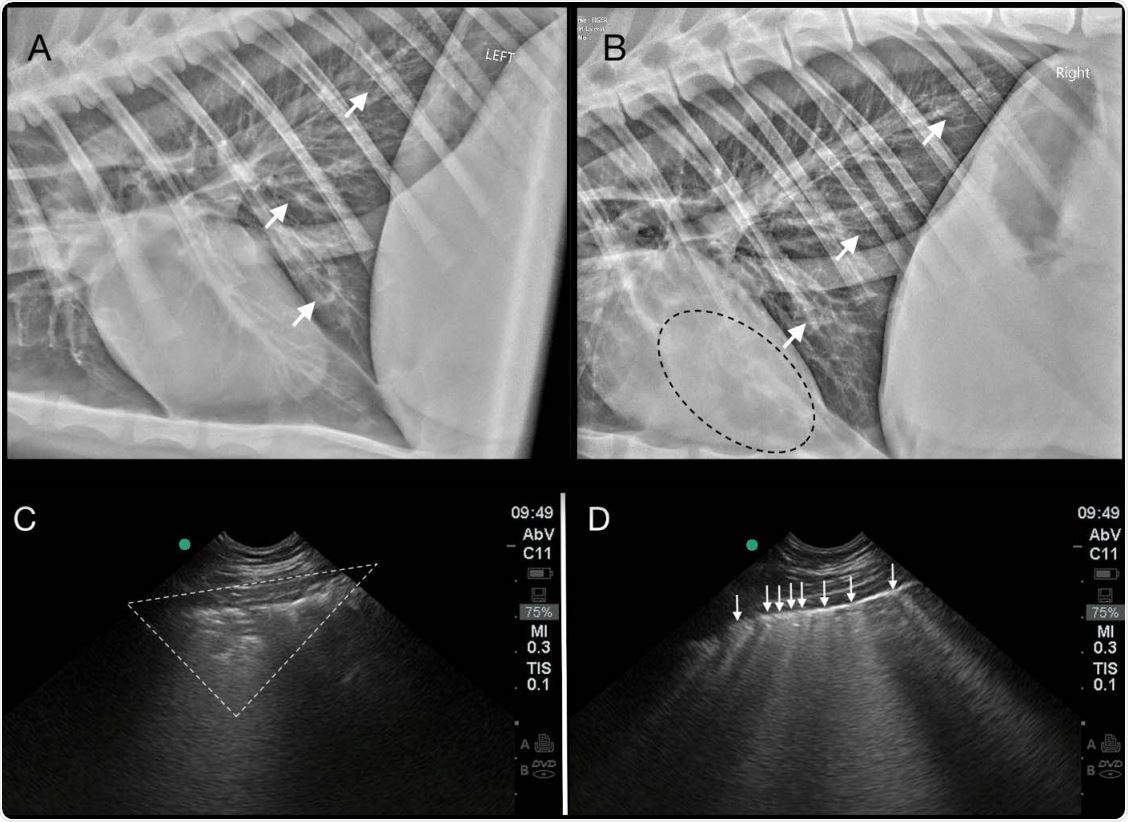

This tissue damage, along with signs of respiratory disease and a “white lung” appearance, is consistent with the imaging results reported for infected humans, say Bartlett and colleagues.

Among most animals, respiratory symptoms resolved within one to five days, although for the index case, coughing persisted intermittently for as long as 16 days. Fecal viral RNA shedding was observed for as long as 35 days after respiratory symptoms had resolved.

Thoracic imaging abnormalities in the index Tiger (T1) with SARS-CoV-2 infection. A generalized bronchial pattern with peribronchial cuffing and bronchiectasis (white arrows) is present in the caudal lung on left lateral (2A) and right lateral (2B) radiographs. Anesthesiaassociated atelectasis is seen as an alveolar pattern superimposed over the heart (black dotted line) (2B). Pulmonary ultrasonography reveals peripheral consolidation (white dotted triangle) (2C), and coalescence of vertical B-lines (white arrows) (2D) indicating AIS (alveolar-interstitial 580 syndrome).

Differences between domestic and non-domestic felids

The authors say that two domestic cats in New York state were found to have SARS-CoV-2 suspected to have been acquired from humans about two weeks following the identification of the tiger infection. Those cats only developed mild respiratory symptoms. The researchers also report that domestic cats experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2 stopped shedding the virus within one week.

“The duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding in feces in these non-domestic felids, with T3, L1 and L2 shedding for more than 3 weeks, was noteworthy, considering that domestic cats experimentally inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 ceased shedding within a week,” writes the team.

“In humans infected with SARS-CoV-2, RNA fecal shedding frequently persists beyond 3 weeks, and shedding persists after cessation of clinical signs or viral RNA detection in sputum, similar to that seen in these non-domestic felids.”

Zookeepers were shedding the virus

Bartlett and colleagues say the tigers and lions appeared to have acquired the infection from zookeepers who were shedding the virus either while having an asymptomatic disease or infection where symptoms had not yet developed.

Prior to T1 becoming ill, zoo staff were never in shared spaces with the animals but were in close contact with them during training and management procedures. Tigers T1 and T2 were also hand raised, meaning they were highly interactive with staff members, which could have made them more susceptible to infection.

At that time, the risk of disease transmission between humans and felids was thought to be low and standard practice did not include wearing face masks while interacting with the animals.

No more cases of felids being infected following new PPE protocols

The researchers report that once new PPE protocols were introduced at all WCS zoos, there were no further cases of infection among tigers, lions, or any other type of non-domestic felid, even though rates of human infection and community spread remained high in New York City throughout June.

“Personal protective equipment should, therefore, be used as a means to minimize the chance of anthropozoonotic transmission of coronaviruses to Felidae and other susceptible taxa,” concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Sources:

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Bartlett S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection And Longitudinal Fecal Screening In Malayan Tigers (Panthera tigris jacksoni), Amur Tigers (Panthera tigris altaica), And African Lions (Panthera leo krugeri) At The Bronx Zoo, New York, USA. bioRxiv 2020. doi: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.14.250928v

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Bartlett, Susan L., Diego G. Diel, Leyi Wang, Stephanie Zec, Melissa Laverack, Mathias Martins, Leonardo Cardia Caserta, et al. 2021. “SARS-COV-2 INFECTION and LONGITUDINAL FECAL SCREENING in MALAYAN TIGERS (PANTHERA TIGRIS JACKSONI), AMUR TIGERS (PANTHERA TIGRIS ALTAICA ), and AFRICAN LIONS (PANTHERA LEO KRUGERI) at the BRONX ZOO, NEW YORK, USA.” Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 51 (4). https://doi.org/10.1638/2020-0171. https://bioone.org/journals/journal-of-zoo-and-wildlife-medicine/volume-51/issue-4/2020-0171/SARS-COV-2-INFECTION-AND-LONGITUDINAL-FECAL-SCREENING-IN-MALAYAN/10.1638/2020-0171.short.