The United States, particularly the western region, is experiencing havoc as wildfires are raging across multiple states. As a result, residents experience plummeting air quality.

Now, health experts worry that the lowered air quality and the smoke produced by the wildfires may increase the risk of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spread, especially among firefighters who are working to stop the fire.

The smoke the firefighters are breathing is heightening their risk of contracting the new coronavirus, with potentially life-threatening effects. Further, fighting the huge fires may make infection control measures such as hand washing and social distancing, challenging to perform.

San Francisco, Ca. 09/09/2020 during the natural disaster of the wild fires. Image Credit: Photo_Time / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Air pollution and health

An environmental toxicologist and an assistant professor of Community and Environmental Health, Boise State University, Luke Montrose, explained the detrimental effects of air pollution, particularly the smoke from wildfires, on health amid the coronavirus pandemic in an article published on the website The Conversation.

He noted that the combination of high temperatures and increased levels of particles from a fire could negatively impact lung health. If a person has lung damage or respiratory illness, even moderate levels of smoke particulate can worsen respiratory problems.

“That’s only the start of the story of how wildfire smoke affects humans who breathe it. The rest, and how to stay healthy, is important to understand as the western wildfire season picks up,” he explained.

Wildfire smoke contents depend on some factors such as what material is burning and the distance between the smoke and the person breathing it. The more distance the smoke travels, the more it ages and becomes toxic. The sun and other chemicals may affect the smoke contents as it travels.

Smoke from wildfires contains thousands of compounds, including toxic chemicals such as carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and carbon dioxide. However, the particulate matter that is less than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) in diameter, which is about 50 times smaller than the grain of sand, is more dangerous since it can enter the lungs and penetrate the alveoli, which are responsible for gas exchange.

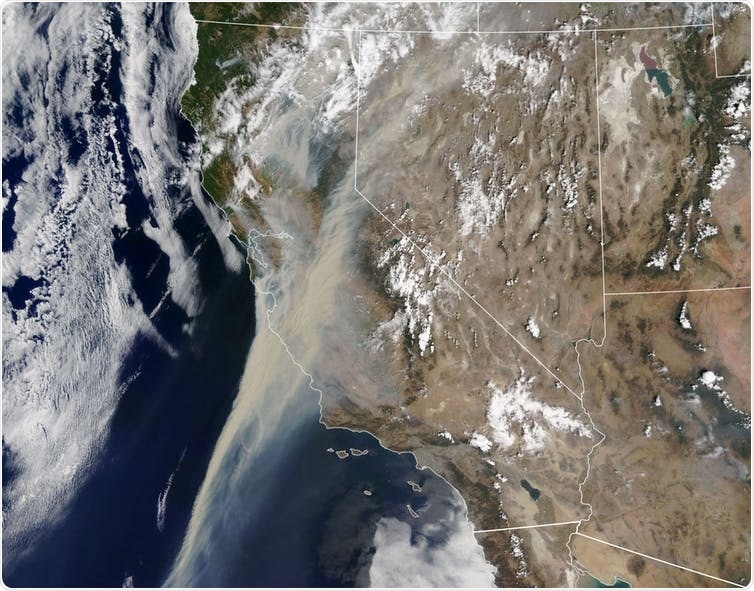

Smoke from wildfires obscures the California sky on Aug. 19, 2020. Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory

What does smoke do to the body?

According to Montrose, the human body has its defense mechanisms against particles that are bigger than PM2.5. The body coughs it out or sneeze when these particles attempt to enter the airways. However, particles smaller than 2.5 can bypass these defense mechanisms and travel deep in the lungs.

When foreign particles enter the lungs, the immune system sends out macrophages in an attempt to remove them. Previous studies have shown that persistent and repeated exposure to increased levels of wood smoke can suppress the function of macrophages, increasing the risk of lung inflammation.

Lung inflammation may predispose people to infections, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The virus causes coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which has now infected more than 29 million people worldwide.

Montrose added that prolonged exposure to wildfire smoke can increase the risk of lung damage, potentially leading to cardiovascular problems. Past evidence reveals that prolonged exposure to PM2.5 may make the coronavirus more severe and deadly.

In a study in the United States, published in the preprint server, medRxiv* in April 2020, scientists have found that long term exposure to PM2.5 may make COVID-19 more deadly.

“A small increase in long-term exposure to PM2.5 leads to a large increase in the COVID-19 death rate,” the researchers concluded.

What can be done?

Avoiding going out can help reduce the risk of smoke exposure, which can affect the air quality outdoors. Also, Montrose recommends that people should be well-informed about air quality and which parts are affected at a given time.

Further, he said that not all face masks may protect against PM2.5 and other smoke particles. In the coronavirus pandemic, health agencies say that cloth masks are enough to protect against the virus. However, cloth masks cannot filter wood smoke particles. In cases of wildfires, using N95 masks is recommended.

He added that proper training on how to use N95 masks is essential since if it is not worn correctly, it will not work well.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Wu, X., Nethery, R., Sabath, B. et al. (2020). Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: A nationwide cross-sectional study. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20054502v2

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Wu, X., R. C. Nethery, M. B. Sabath, D. Braun, and F. Dominici. 2020. “Air Pollution and COVID-19 Mortality in the United States: Strengths and Limitations of an Ecological Regression Analysis.” Science Advances 6 (45): eabd4049. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abd4049. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abd4049.