The observed increase in COVID-19 cases coinciding with the reopening of college campuses all over the US has drawn intense scientific attention. A recent paper, by Washington State University researchers, published on the preprint server medRxiv* in September 2020 reports that this threat is directly linked to the holding of in-person sporting events on these campuses.

The current COVID-19-related situation has inevitably ignited a debate as to the role played by college reopening, with the main focus being on whether in-person instruction is safe or necessary during this period. An integral part of such a controversy relates to the sporting events organized by these colleges, notably college football.

Fall is marked by the start of the regular college football season, which means enormous profits to the colleges that host the games – to the tune of many millions of dollars. These games attract crowds, and the lead-up involves many players who are coached daily for many months beforehand.

As of now, many of the leading college football leagues, including the Ivy League and Big Ten, have canceled their seasons, or at least delayed the start. However, these are economically painful decisions, and many institutions will attempt to organize at least a trimmed version of their football season.

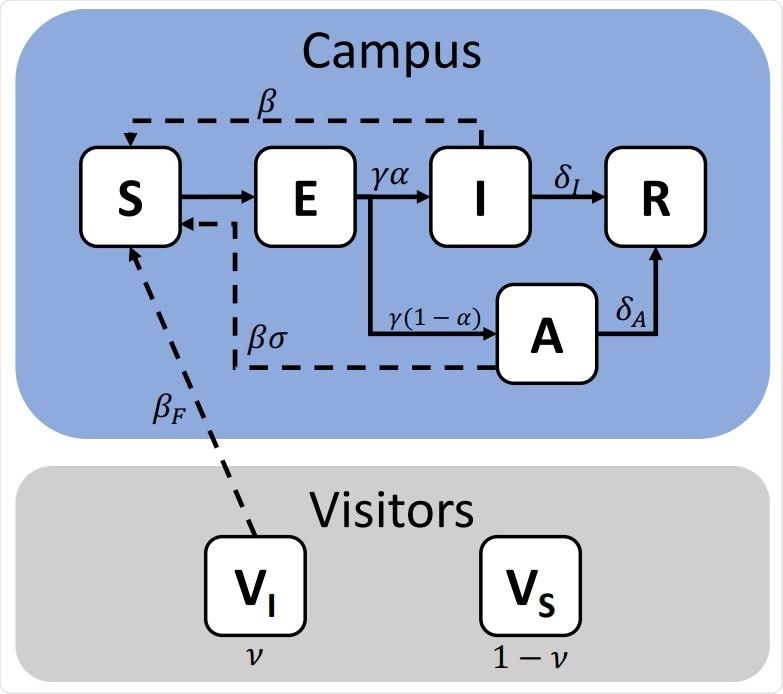

Schematic representation of a model of COVID-19 transmission due to in-person sporting events. The campus population is shown within the blue field, while visitors are shown within the grey field. The campus population can take four health states – Susceptible (S), Exposed (E), Infectious (I), Asymptomatic (A) or Recovered (R), while visitors are represented as two states, Susceptible (VS) or Infectious (VI). Solid arrows denote transition terms, while dashed arrows denote potential transmission pathways. The relevant parameters for each are also shown.

Safe Sporting Events?

A leading aspect of such decisions is the safety of such events, which includes the ability to restrict severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission between players during the game, how to organize spectators such that social distancing is observed, and how to maintain safety norms for the team players, coaches and other staff during routine practices and during the trips to and from the various far-flung venues of the games.

Such decisions will require the input of much knowledge, “ranging from the epidemiology of COVID-19 to the built environment of locker rooms,” said the organizers. The current study, therefore, limits itself to the single question of whether and how the abrupt and transient convergence of large numbers of visitors on a college for the purpose of such a sporting event, along with other associated activities like visiting bars and restaurants, eating meals around a parked vehicle and other forms of interaction with the local student and town communities.

Using a mathematical model to understand how such regular large-scale mixing of outsiders with local residents and college students would affect the COVID-19-related health risk, the researchers examined two baseline scenarios first. In one, the campus had a transmission number R0 of just below, with a median ~216 cases among students on campus. In the other, R0 was just above 1, and the number of local cases was >1,100 cases. The first was a small outbreak, while the other was an uncontrolled situation.

Campus R0 < 1

When the campus had a small outbreak, the median case number was 216 in the absence of any in-person sporting event. When visitors from another community with a low case prevalence were included in the model, there was an increase to a median of 330 cases, representing a 52% increase, even if the rate of interactions between the students and the visitors is assumed to be low. If there is extensive mixing, the increase in cases is above 100%, with a median of 437 cases.

If the visitors are from a high prevalence population, the median number of cases rose to well above 1,100 and ~2,000, in the low- and high-mixing simulations. This corresponds to a rise in cases by 452% and 822%, respectively.

Campus R0 > 1

The second control scenario envisaged by the researchers has to do with a campus in which the R0 is still over 1, indicating an uncontrolled outbreak is occurring. Here, the baseline case incidence is at ~1,100, but with an influx of visitors from a low-prevalence setting, and with restricted interactions, this increases by 25% to a median of 1,400 cases.

With unrestricted mixing between visitors and college students, the number of cases is shown to rise by 43% to a median of 1596 cases.

If the visitors are from a high-prevalence community, the increase in scenarios involving low and high levels of interaction results in a median of ~3,100 and ~4,500 cases for an increase of 177% and +304%, respectively.

The researchers also found that the first scenario, with R0 less than 1, but with sporting event visitors from a high-prevalence area and with free interactions between local students and visitors, was likely to result in an 11-fold hike in the number of COVID-19 cases compared to the same campus without in-person sporting activity.

Implications

In four different simulations centering around the occurrence of in-sporting events during a period when COVID-19 is not yet contained, the number of cases on the campus is found to register a significant increase.

The proportion of increase, though not the absolute case burden, is especially striking in campuses where the R0 had dropped below 1. This indicates that allowing periodic exposure to infectious cases from outside had the effect of either triggering a fresh outbreak or disrupting the natural extinction of the ongoing outbreak.

When the outbreak was not yet controlled, the case number, already large, surged to much higher levels, which could overwhelm the healthcare system’s local capacity. This could mean that more people succumb to the disease because of the local shortage of medical care facilities in the face of a steep surge in requirement.

While visitors from low- and high-prevalence areas affected the median number of cases differently, even as few as 10 infectious visitors out of a total of 10,000 produce outbreaks of substantial size.

The study concludes that “in-person sporting events represent a considerable health risk to the campus community,” and that “risk-free in-person sporting events are not necessarily possible for the foreseeable future.”

It is important to note that all these simulations dealt only with cases arising from interactions between visitors and students on the campus, ignoring transmission between players, within the community, and between visitors. Even such optimistic projections indicate the potential for hundreds of new cases to arise from in-person sporting events.

The researchers say that given numerous uncertainties about the disease and its seasonal dynamics, “it seems prudent from a public health perspective to seriously consider the cancelation of in-person sporting events on college campuses for the duration of the pandemic, or at least until a widespread and effective vaccine is available.”

Source

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources