SARS-CoV-2 is the agent responsible for the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) pandemic that continues to pose a significant threat to public health and the economy globally.

However, according to the modeling estimates, adherence to isolation measures and the implementation of effective testing and contact tracing would curb transmission of the virus in the university setting. This adherence would also reduce the risk of asymptomatic individuals unknowingly transmitting the virus to family and community members once they return home at the end of the term.

"These results show the possible impact of SARS-CoV-2 transmission intervention measures that may be enacted within a university population during the forthcoming academic year," said Edward Hill and colleagues.

A pre-print version of the paper is available in the server medRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

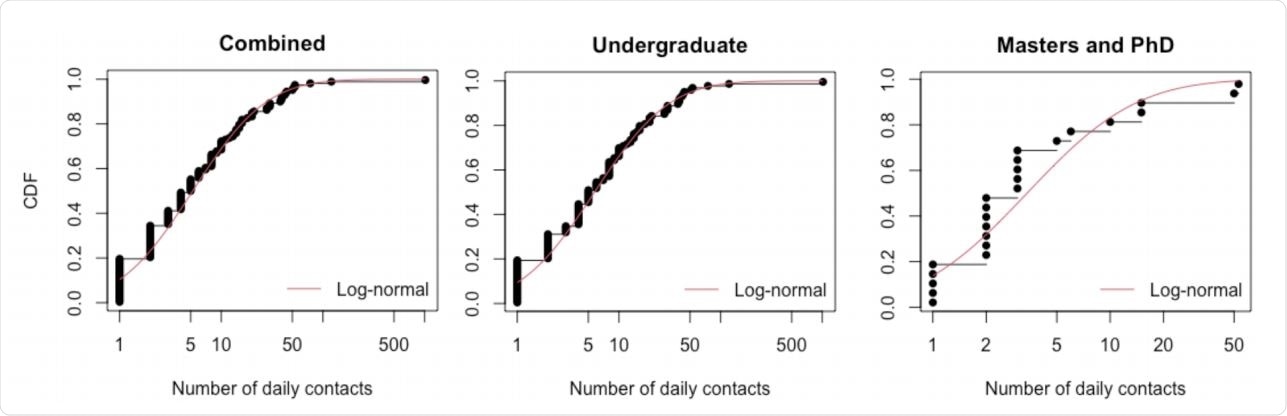

Cumulative distribution functions for number of daily cohort contacts for all students, undergraduates and postgraduates. Black dots and lines depict the empirical data. The red solid line corresponds to the best-fit lognormal distribution.

Efforts to curb transmission so far

Since the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 were identified in Wuhan, China, late last year, the unprecedented spread of the virus has led many countries to implement control measures in efforts to curb transmission.

In the UK, the introduction of lockdown on March 23rd, 2020, saw the closures of workplaces, restaurants, pubs, entertainment centers, and educational establishments such as schools and universities.

Once the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths began to fall, many sectors of society started to re-open, including the education sector, with control measures put in place to reduce the risk of transmission.

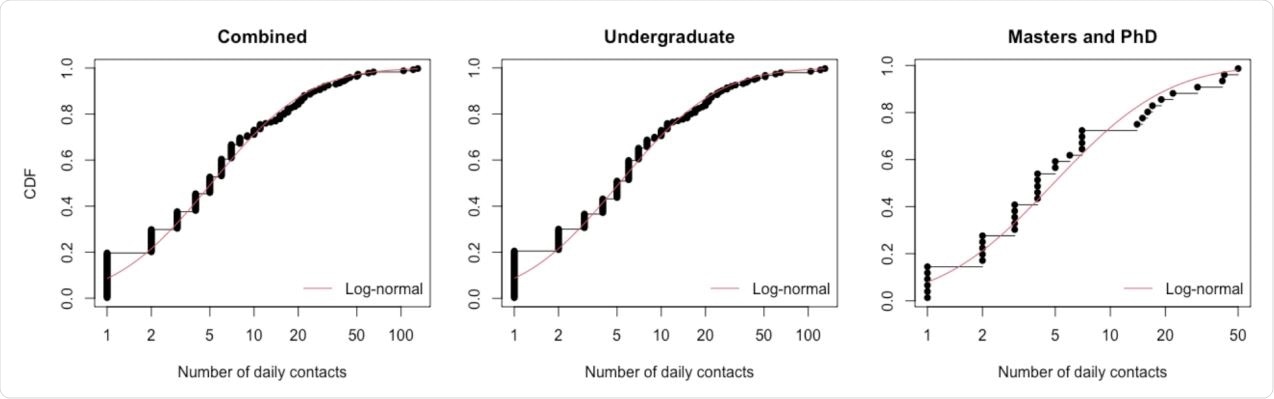

Cumulative distribution functions for number of daily social contacts (outside of society and sports clubs) for all students, undergraduates and postgraduates. Black dots and lines depict the empirical data. The red solid line corresponds to the best-fit lognormal distribution.

Contact patterns among students could increase spread

Around 40% of school leavers go on to university in the UK, with each university accommodating thousands of students every academic year.

The typical contact patterns among students could mean the virus is easily spread within their social group, thereby increasing the risk of transmission to staff members and people in the local community.

Furthermore, since students are of an age where the asymptomatic infection is more likely, they could unwittingly transmit the virus to family members once they return home at the end of the term.

"Bringing together these student communities during the COVID-19 pandemic may require strong interventions to control transmission," said Hill and team.

Previous modeling studies of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within the university setting have suggested that outbreaks are almost inevitable.

However, many of these analyses have adopted compartmental modeling approaches, which do not readily capture individual behaviors and contact tracing interventions.

What did the researchers do?

Now, Hill and the team have used an individual-level network-based model they developed to capture the interactions within a UK campus-based student population. They assessed transmission in the household, study, and social settings over a single academic term and investigated the impact of adhering to isolation, test and trace measures, single-room isolation, and supplementary mass testing.

The team reports that in the absence of interventions, the model estimated that around 16% of the student population could become infected with SARS-CoV-2 over the course of the autumn term.

However, with full adherence to isolation guidance and engagement in testing and contact tracing, the model estimated a significantly lower cumulative infection rate of just 1.4%.

The team says adherence to these measures could both reduce infection throughout the academic term and limit the prevalence of the virus at the beginning of the winter break when students return home.

"The importance of monitoring the situation in halls of residence"

The model also predicted that a higher proportion of the on-campus population would become infected irrespective of adherence to isolation than the off-campus population.

The researchers say that household sizes within on-campus halls of residence are typically larger than the off-campus households. A higher level of mixing and an associated increased risk of infection is therefore expected.

"This outcome reinforces the importance of monitoring the situation in halls of residence, in agreement with prior studies," said Hill and colleagues.

Mass testing on a regular basis was most effective

The use of room isolation and a single instance of mass testing offered marginal benefits. However, mass testing on a regular weekly or fortnightly basis could reduce the term-long caseload or end-of-term prevalence by more than half, say the researchers.

"Our findings demonstrate the efficacy of isolation and tracing measures in controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2 if they are broadly adhered to," writes Hill and colleagues.

"This model suggests that encouraging student adherence with test-trace-and-isolate rules (as well as good social-distancing, mask-use, and hygiene practices) is likely to lead to the greatest reduction in cases both during and at the end of term," concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources