The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has highlighted humanity's vulnerability to novel viruses.

Modern human genomes contain evolutionary information tracing back tens of thousands of years. This genetic information helps us identify viruses that had affected ancient people.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

A new study by researchers at the University of Adelaide and Australian National University in Australia and the University of Arizona in the US shows that an ancient coronavirus-like epidemic drove the adaptation of East Asian peoples from 25,000 to 5,000 years ago. The findings of their study were made available on the preprint server bioRxiv* in November 2020.

Study background

Over the past two decades, strains of coronaviruses created three major outbreaks with significant human impacts. The first outbreak, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), occurred in China in 2002. The epidemic infected over 8,000 people and claimed nearly 800 lives.

A couple of years later, the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) affected about 2,400 people and caused over 850 deaths in Saudi Arabia.

The most recent outbreak started in December 2019 in Wuhan City in China. Though less virulent and deadly, the coronavirus disease is far more contagious. The outbreak has caused over 55.76 million people and at least 1.34 million deaths.

With the magnitude of the current pandemic, research efforts have been mounted to develop new vaccines and therapies to curb its impact. Some scientists have focused on determining the factors that underlie the infection's epidemiology.

Past evidence suggests that ancient viral epidemics have occurred regularly in the history of the humanity. However, it remains unclear if this has made a marked contribution to population-level differences in SARS-CoV-2 responses today.

The study

The researchers investigated whether ancient coronavirus epidemics have generated genetic differences within and across modern human populations.

The team investigated if selection signals are enhanced within a set of VIPs specific to the coronavirus. They scanned 26 diverse human populations from five continents to prove strong selection acting on proteins that interact with coronavirus strains (CoV-VIPs).

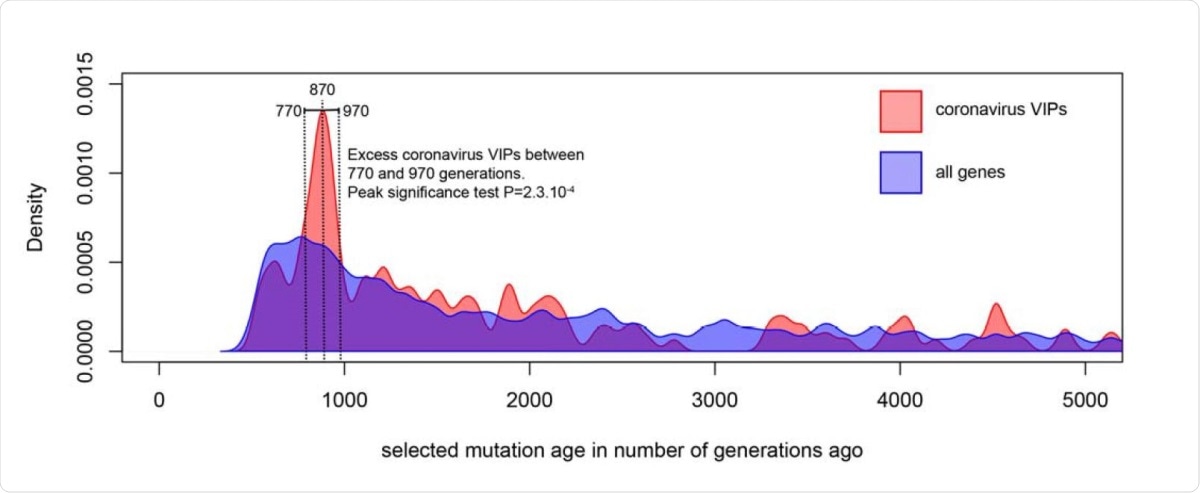

The team identified 42 CoV-VIPs manifesting a coordinated adaptive response that emerged way back (around 25,000 years ago), equating to 900 generations.

Accordingly, the pattern seen was unique to the ancestors of East Asians. The team also noted that the selection pressure created a robust response across the 42 CoV-VIPs genes.

The researchers explained that the adaptive response is probably the result of a multigenerational coronavirus epidemic.

Timing of selection at CoV-VIPs: The figure shows the distribution of selection start times at CoV-VIPs (pink distribution) compared to the distribution of selection start times at all loci in the genome (blue distribution). Details on how the two distributions are compared by the peak significance test, and how the selection start times are estimated with Relate, are provided in STAR Methods.

One feature of the adaptive response seen is that selection appears to be continuously happening over 20,000 years. This means that coronavirus pandemics have been occurring throughout history. For instance, in recent years, coronavirus epidemics occurred approximately every decade, suggesting that the pattern may have occurred throughout history in East Asian peoples.

The team concluded that they could infer ancient viral epidemics affecting the ancestors of East Asian populations. This resulted in coordinated adaptive chances across at least 42 genes.

"Our findings highlight the utility of incorporating evolutionary genomic approaches into standard medical research protocols. Indeed, by revealing the identity of our ancient pathogenic foes, evolutionary genomic methods may ultimately improve our ability to predict – and thus prevent – the epidemics of the future," the researchers explained.

Continuously spreading

Understanding how populations respond to the current pandemic can help scientists develop new therapies and vaccines to curb its spread.

So far, there is still no treatment and vaccine available for COVID-19.

In the United States, the total number of cases has topped 11.36 million, with more than 248,00 deaths. Countries such as India and Brazil report over 8.91 million and 5.91 million cases, respectively.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Lauterber, E., Tobler, R., Huber, C., Johar, A., and Enard, D. (2020). An ancient coronavirus-like epidemic drove adaptation in East Asians from 25,000 to 5,000 years ago. bioRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.16.385401, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.16.385401v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Souilmi, Yassine, M. Elise Lauterbur, Ray Tobler, Christian D. Huber, Angad S. Johar, Shayli Varasteh Moradi, Wayne A. Johnston, Nevan J. Krogan, Kirill Alexandrov, and David Enard. 2021. “An Ancient Viral Epidemic Involving Host Coronavirus Interacting Genes More than 20,000 Years Ago in East Asia.” Current Biology 31 (16): 3504-3514.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.067. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)00794-6.