Researchers modeled the health benefits and economic loss caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the UK and compared them to four other western European countries. Their results suggest the British Government’s response may outweigh the economic loss incurred.

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in significant damage to public health and economic wellbeing.

There have been more than 74.28 million confirmed cases and over 1.65 million deaths worldwide.

The economic damage has also been severe, with the gross domestic product (GDP) around the globe forecast to decrease dramatically. For the United Kingdom (UK), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has reduced its GDP growth from 1.4% in January 2020 to -9.8% in October 2020.

The COVID-19 prevention strategy of social distancing has been questioned because of its adverse impact on the economy and employment. Previous studies have tried to compare the benefit of social distancing and economic loss. One found lives saved by lockdown would outweigh GDP losses, while others found the cost of quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) to be £50,000 or £220,000 in another case. These suggested the response in the UK was not cost-effective. However, none of these studies made any international comparisons.

Comparing net health benefit and economic loss

In a new study published on the medRxiv* preprint server, researchers from the University of Bristol compared the net health benefit and associated GDP loss in the UK, Ireland, Germany, Spain, and Sweden during the first wave of COVID-19 between 1 January 2020 and 20 July 2020.

The researchers used a new model that assessed cost and QALYs of COVID-19 hospitalization, and deaths and QALYs lost per death. They reviewed different governments' responses, including lockdowns, mask-wearing orders, international travel regulations, and school and workplace closures.

They used the numbers available for each country for the number of cases, hospitalization, and deaths for determining outcomes under ‘mitigation.’ They modeled outcomes if there was no mitigation using the CMMID COVID-19 model. They calculated the QALYs lost and healthcare costs for the ‘mitigation’ and ‘no mitigation’ case.

Other than Sweden, response measures and their timings were similar in all the countries. Hospitalizations and deaths per capita were lower in Ireland and Germany than those in Sweden, Spain, and the UK.

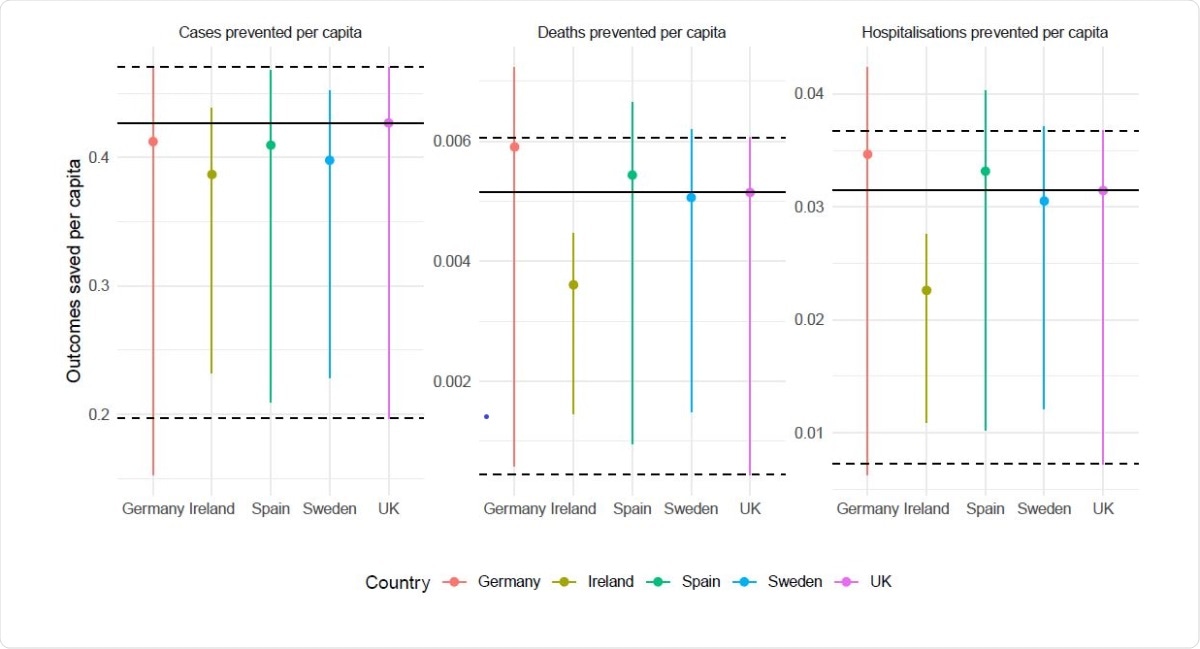

In a base case scenario where the reproduction number (R0) was 2.7, Spain and Germany had lower deaths per capita than the UK; Sweden was similar to the UK, and Ireland prevented fewer deaths and hospitalization than all countries. The health-related net benefits (HRNB) per capita are highest for Germany, then Spain, UK, Sweden, and a distant last was Ireland in this case.

In another scenario with an R0 of 1.6, Sweden and Ireland have the most significant health-related benefit while the UK and Germany have the lowest.

In a third scenario with an R0 of 3.9, the trend is similar to that of the base scenario. Across all scenarios, the UK response is estimated to have saved around 3.17 million QALYs, £33 billion in healthcare costs, and gained about £1416 per capita health-related net benefit. This is similar to the £1455 GDP loss per capita for Sweden, which had minimal mitigation strategies.

Outcomes saved per capita (PP). Central estimate is scenario A while lower and upper limits correspond to scenarios B and C, respectively. Horizontal solid lines indicate UK estimates for ease of comparison. Values above these lines indicate greater benefit per capita. Comparison of cases is affected by levels of testing so focus should be on deaths and hospitalisations.

GDP loss may not be only because of government restrictions

Comparing the economic loss, the authors found that the UK and Spain had the worst GDP loss and Sweden the least. In the base case scenario, all countries suffered GDP loss, with the loss ‘offset’ by net health benefits ranging from 30% in Ireland to 71% in Germany. In the UK, about 46% of GDP loss was offset by the health-related net benefit.

Germany's best performance is likely due to higher testing, early mask-wearing, and higher median age. The reason for Ireland’s worst performance could be the low probability of COVID-19 hospitalization and death likely due to a younger population.

However, using Sweden as comparator and comparing across countries, we argue that GDP loss is not purely due to government restrictions and that restrictions may be outweighed by HRNB,” write the authors.

It is not realistic to only attribute this to the government response or argue that any other European country could have prevented GDP loss or implemented no mitigation strategies. Rather than imposing strict restrictions, countries that did well on offsetting GDP loss with health-related benefits had a higher at-risk population, higher testing, and mask-wearing.

The authors suggest decision-makers use cost and the associated QALYs rather than only total numbers. Higher testing and mask-wearing seem to be more beneficial than a strict response. Considering the demographics and interpersonal contact, policies applied on a regional rather than a national level could be more useful.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources