Researchers investigating attitudes towards vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) among the UK population have found that, overall, most people were willing to accept a vaccine.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is the agent responsible for the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that continues to pose a significant threat to global public health and the worldwide economy.

The study also found that certain subgroups of the population were unlikely to accept a vaccine (vaccine-hesitant), which has important implications for public health policy, says the team.

The analysis of nationally representative survey data found that 82% of participants were likely to accept a vaccine. However, women, younger individuals, and those with lower education levels were more likely to be vaccine-hesitant.

Certain ethnic groups, particularly Black, Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals, were also more likely to be vaccine-hesitant.

The team – from the University of Glasgow, University of Essex, Public Health Scotland, and Ipsos MORI UK Ltd – says the main reason for vaccine hesitancy was concerns over unknown future effects.

Given that the UK is now rolling out a vaccination program, these findings have important implications regarding the steps that need to be taken to increase uptake, say the researchers.

“Herd immunity may be achievable through vaccination in the UK, but a focus on specific ethnic minority and socioeconomic groups is needed to ensure an equitable vaccination program,” writes Michaela Benzeval (University of Essex) and colleagues.

A pre-print version of the paper is available on the medRxiv* server while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

A safe and effective vaccine is crucial to controlling COVID-19

The wide-scale administration of an effective and safe vaccine against SARS-COV-2 is crucial to bringing the COVID-19 pandemic under control, but vaccine hesitancy could undermine such efforts.

Ideally, the proportion of the population vaccinated would be large enough for those who remain unvaccinated to also be protected (referred to as herd immunity).

Understanding whether some subgroups may be more likely to accept or refuse a vaccine is critical to designing successful vaccination strategies for achieving herd immunity.

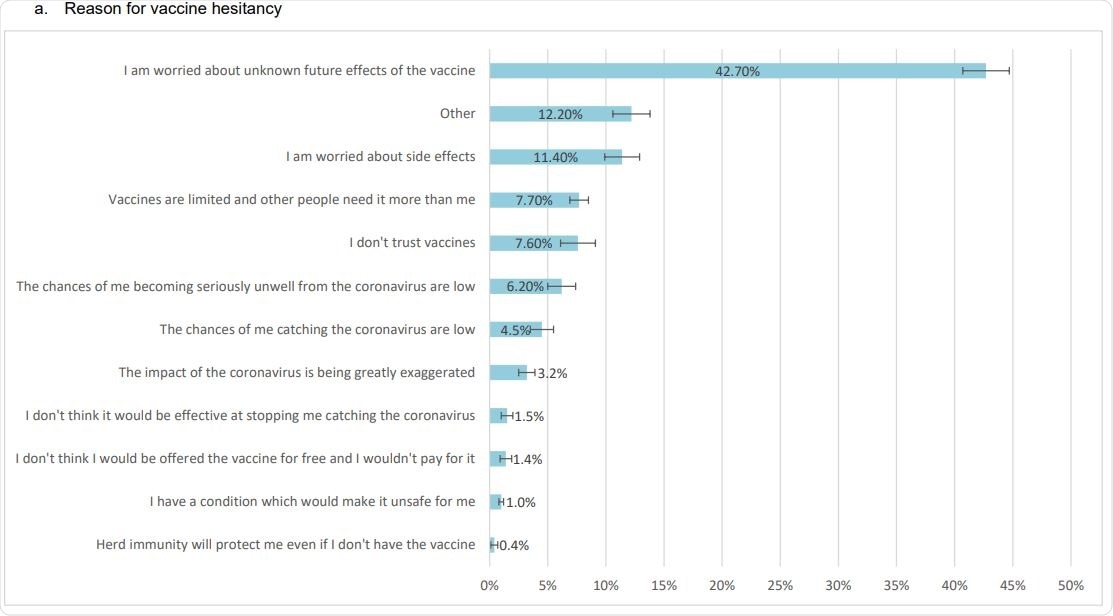

Reasons for vaccine hesitancy, willingness to take vaccines and factors that would persuade people to take a vaccine (weighted proportions with 95% CI bars)

What did the researchers do?

Nationally representative data available for 12,035 individuals participating in wave 6 of the “Understanding Society” COVID-19 web survey were collected from 24th November to 1st December 2020.

Participants were asked how likely or unlikely they would be to receive a vaccine and the reasons why.

“The four countries of the UK are now rolling out a vaccination program commencing with those most at risk of mortality from COVID-19,” writes the team. “The findings reported here provide evidence on the groups who need targeting and arguments that may be most persuasive for them.”

Hesitancy varied significantly between subgroups

Overall, the intention to be vaccinated was high, with 82% of respondents reporting that they were likely (28.5%) or very likely (53.5%) to have a vaccine. However, 18% reported that they were unlikely or very unlikely to have the vaccine.

The intention to be vaccinated varied significantly between population subgroups.

A higher proportion of women indicated vaccine hesitancy than men, at 21.0% versus 14.7%, and a higher proportion of younger age groups indicated vaccine hesitancy, compared with older age groups.

Among those aged 16 to 24 years and those aged 25 to 24 years, vaccine hesitancy was 26.5% and 28.3%, respectively. This compared with 14.3% among those aged 55 to 64 years, 8.1% among those aged 65 to 74 years and just 4.5% in those aged 75 years or older.

“Older age and being male are strongest drivers of the risk of COVID-19 death, they are less likely to be vaccine-hesitant, suggesting the vaccination program could yield large health benefits within the UK,” says Benzeval and the team.

Vaccine hesitancy also significantly varied by ethnicity, with Black (71.8%) and Pakistani/Bangladeshi (42.3%) groups being the most hesitant, followed by those of mixed ethnicity (32.4%) and non-UK/Irish White individuals (26.4%).

People with lower education levels were also more likely to be vaccine-hesitant. Among degree-qualified individuals, 13.2% reported being vaccine-hesitant, compared with 24.6% of those with GCSEs and 18% of those with no qualifications.

Overall, the main reason reported for hesitancy was concerns over unknown future adverse effects of a vaccine, with 42.7% citing this as the reason.

The main reasons for being willing to have a vaccine were to avoid catching the virus or becoming very ill (54.6%) and to allow social and family life to return to normal (12.5%).

The study also found that knowing a vaccine is effective and safe were the main factors that would encourage vaccine uptake.

What are the implications of the study?

“Our study has important practical implications for public health policy,” writes the team.

The risk of vaccine hesitancy varies significantly across minority ethnic groups in the UK, with Black, Pakistan and Bangladeshi groups particularly likely to be vaccine-hesitant, say the researchers.

“People with lower education levels were also more likely to be vaccine-hesitant,” they add.

Benzeval and colleagues say vaccine hesitancy is a complex problem and that a range of practical steps need to be taken to increase uptake.

“The subgroups we have identified as being vaccine-hesitant should be included in the planning and development of any engagement programs,” they conclude.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Benzeval M, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK Household Longitudinal Study. medRxiv, 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.27.20248899, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.27.20248899v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Elaine Robertson, Kelly S. Reeve, Claire L. Niedzwiedz, Jamie Moore, Margaret Blake, Michael Green, Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi, Michaela J. Benzeval. 2021 “Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the UK Household Longitudinal Study.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, March. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889159121001100.