When the pandemic hit Israel, every aspect of our lives has changed, and therefore like many other laboratories we had to put on hold some ongoing projects and focus on the new virus.

In fact, we have been developing tools and platforms for antibody discovery and isolation for a very long time, while focusing on other infectious diseases such as HIV-1 and Tuberculosis, and we were as prepared as one can be to apply our tools to the new COVID-19 problem.

So, at the beginning of March, we started collaborating with two hospitals in Israel, Ichilov Center and Kaplan Centers where COVID-19 patients were enlisted and started investigating the natural antibody responses in people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 while addressing questions such as what antibodies are produced in infected individuals, what is the interaction between disease severity and the immune response, and what is the level of immunity that will prevent re-infection.

SARS-CoV-2. Image Credit: Cristian Moga/Shutterstock.com

What are neutralizing antibodies and how do these differ from other types of antibodies?

Antibodies are proteins made by cells of our immune system called B cells. They are produced upon infection or vaccination, and they are very specific to the disease they are produced against.

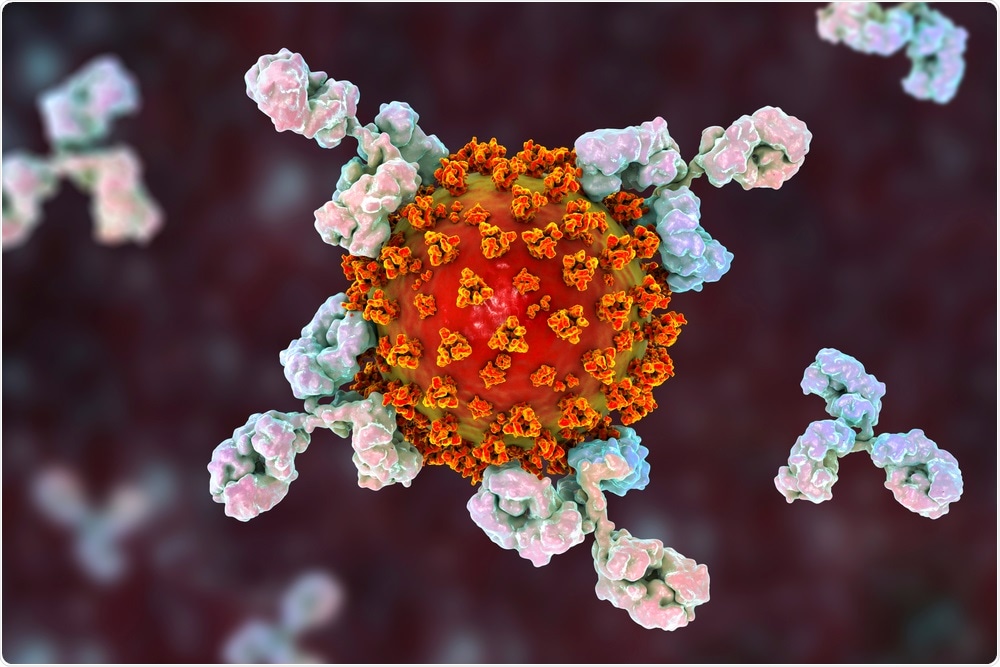

Neutralizing antibodies are a specific subtype of antibodies that can physically block the virus from entering the cell and replicating. This is done by antibody binding to “weak spots” within the virus, and it is the binding itself that stops the virus from further going on with its life cycle.

The levels of these antibodies vary from one person to another, but once produced, even when their levels decay, there is immunological memory that is retained and these antibodies can be easily re-produced upon second exposure.

Can you describe how you carried out your latest research? What did you discover?

Our main goal was to understand whether people who got infected with SARS CoV-2 develop neutralizing antibodies and against what targets on the virus. Additionally, we asked what is the correlation between the antibody responses and disease severity.

At first, we thought that higher levels of neutralizing antibodies are related to lack of severe disease, but we actually found out the opposite: it turns out that people with very mild disease have fewer neutralizing antibodies compared to those who had severe symptoms.

Now we understand that during severe disease, the patient has a lot of viruses and this stimulates his immune response to produce more neutralizing antibodies, compared to asymptomatic infection where the infection can be somewhat “invisible” to the immune system.

Antibodies attacking SARS-CoV-2 virus. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

What is combination antibody therapy and how do your results also support the use of this for preventing and treating COVID-19?

Combination antibody therapy is mixing monoclonal antibodies that bind different “weak spots” on the virus and therefore can simultaneously block the virus in several places. The idea of a drug cocktail was first used in HIV-1 therapy when clinicians realized that using only one drug resulted in a quick viral escape when the virus made mutations in the specific place the drug was targeting.

On the other hand, attacking several sites at once reduces the chances of such “escape mutants” to almost zero, making therapy very effective. Antibody combination therapy relies on a similar concept; using only one antibody allows the virus to escape by sometimes making only one mutation, while when using two or even three monoclonal antibodies together requires the virus to simultaneously mutate two or three different sites at once, which is practically not possible. However, to use such combinations of neutralizing antibodies one has to discover antibodies targeting different sites on the virus.

Luckily, using our tools and with the help of our collaborators in Israel and the US who tested the antibodies we isolated for neutralization, we were able to find many different neutralizing antibodies’ types in our patients. Eventually, we focused on three main families of neutralizing antibodies. When we mixed these antibodies together we got extremely effective blocking of the virus in culture over several days.

As well as vaccinations, why is it important for clinicians to have specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics?

An antibody cocktail is what we call a passive vaccine. Whereas an active vaccine is given to healthy people and its purpose is to induce the body to produce neutralizing antibodies and immune memory to protect from future exposures, a passive vaccine is when we are providing the protective immune response from the outside, as a drug.

Even now with the incredible vaccination efforts around the world, we still have infections and hospitalizations due to severe COVID-19. Also, some people have immunodeficiencies or immune suppression and it is unclear whether they can make specific antibodies following vaccination.

Therefore, it is important to arm clinicians with weapons against this virus. Monoclonal antibodies have proven extremely efficacious biological drugs with minimal side effects, and they can be used to treat a person with high viral loads to prevent severe disease manifestations.

How was bioinformatics used within your research?

Our laboratory is what is called a “wet laboratory,” so we were very lucky to have strong computational partners to do this part. Once we identified neutralizing antibodies in our cohort of convalescent donors, and we were able to recognize their genetic footprints, we went to search for these footprints in healthy, uninfected donors’ samples that were collected before COVID-19 broke into our consciousness.

Using bioinformatics tools we were able to identify the precursors for anti-COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies in almost every healthy donor. This is very good news since it means that upon vaccination or infection almost everyone can produce these neutralizing antibodies, that will protect the vaccinated/ infected person in the future.

Bioinformatics Concept. Image Credit: CI Photos/Shutterstock.com

Do you believe that your research will help us further understand SARS-CoV-2 and our body’s immune responses to this virus?

I must admit that during the past year I was feeling ambivalent about SARS-CoV-2; on one hand this year has posed enormous economic, personal, and social challenges. On the other hand, we all witnessed outstanding science in all its glory.

A year ago, we knew so little about this virus, and look, now we have already four approved vaccines that are given to millions, and several tens of drugs in clinical testing. Many laboratories around the globe, including my former mentor Michel Nussenzweig, did incredible work on antibodies and vaccines.

In this context, I feel that our work fits nicely into this general trend of discoveries that can help end this pandemic and prepare better for future ones.

What are the next steps for your research?

Well, first we are still looking for pharma partners to take our antibodies to the next clinical-stage, to be tested in people. We also keep collaborating with vaccine centers in Israel to try to understand the longevity of antibody responses following infection and vaccination, and we try to understand how the neutralizing antibodies elicited in vaccinees and infected people perform against the new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

We must remember that this is an ongoing race, and while we make progress in COVID-19 prevention and therapy, the virus evolves trying to overcome our efforts. To win this race we have to keep an open eye on the new variants while continuing to develop new anti-viral strategies.

Where can readers find more information?

Labs website: http://www3.tau.ac.il/nfreund/

About Dr. Natalia Freund

Dr. Natalia Freund is specializing in antibody responses towards infectious diseases. Natalia has completed for Ph.D. from Life Sciences Faculty at the Cell Research and Immunology Department of Tel Aviv University focusing on the first SARS Coronavirus. She then moved to The Rockefeller University in New York City as part of her postdoc, where she investigated the antibody responses to HIV-1 in infected individuals.

In 2017, she joined the Sackler School of Medicine of Tel Aviv University as an Assistant Professor and a faculty member. In TAU she is continuing to apply single-cell methods to investigate the human antibody response during disease. She is the awardee of several grants and prizes, such as the doctoral Clore fellowship, TAU Breakthrough Prize, and Israeli Science Foundation grants.