Current methods of limiting the spread of COVID-19 infection in schools are unsuited for controlling outbreaks, with research indicating that regular monitoring measures may be better suited.

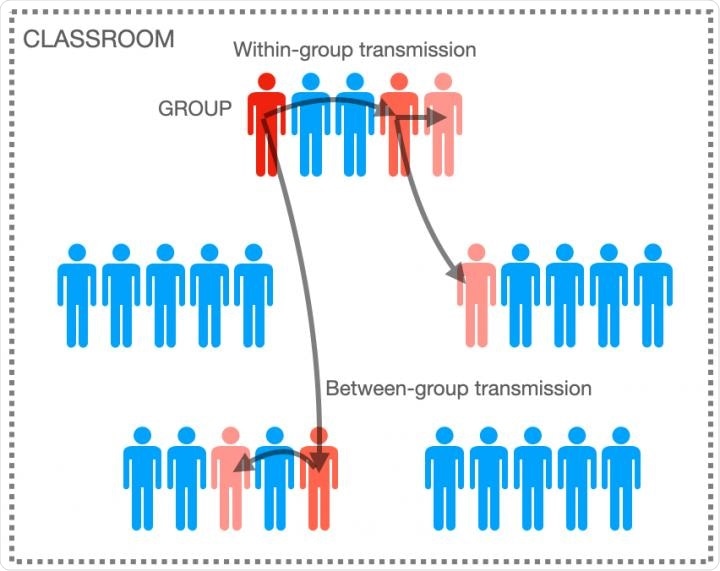

Classroom Transmission. Image Credit: Paul Tupper

Simulations of classroom dynamics show current preventative measures are inadequate to control COVID-19 outbreaks

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the closure of schools occurred frequently and was a common measure to avoid larger outbreaks. Such closures are costly for the students and teachers, and many countries have recently reopened schools whilst using a suite of potential control measures.

Moreover, an important area of uncertainty relating to the study of COVID-19 infection is just how transmissible the virus is between people occupying public areas. Classrooms are characteristically spaces of frequent interactions between people, with limited opportunities to implement social distancing, preventative hygiene, and largescale testing. As a result, many schools have experienced rapid and severe outbreaks, and have implemented control measures in response.

Preventative measures vary between countries, but typically involve body temperature measurements, PCR tests for COVID-19 infection if students have traveled, as well as classroom closures if a student has tested positive.

However, a new study by Paul Tupper, from Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada, and Caroline Colijn from the Department of Mathematics at Imperial College London, London, UK, has shown that current methods may be inadequate.

The study published in PLOS Computational Biology uses mathematical models to simulate classrooms and examines the factors that underlie COVID-19 outbreaks in schools. Simulations included differences between infected individuals in how easily they can transmit the disease to others, and differences in transmission rates for different environments and activities to determine how these two qualitative factors may affect outbreak control.

Infection rates vary across scenarios but are only mitigated using regular monitoring

The simulations showed that in a classroom with 25 students, anywhere from 0 to 20 students might be infected after initial exposure, depending on even small adjustments to transmission rates for infected individuals or environments.

Then, researchers simulated the effects of different protocols to prevent large clusters of infection across classrooms and found that in scenarios with high transmission rates, preventive actions (such as closing down a whole class) that only took effect after a student developed symptoms and tested positive were too slow to prevent large outbreaks.

Simulations clearly showed that large outbreaks could only be prevented with regular monitoring of everyone in the setting, for example with pooled rapid testing on site.

We found that waiting until a student develops symptoms and tests positive is too slow a response, even though this was the method used in many jurisdictions to prevent COVID-19 transmission. Screening students without symptoms works quite well in our model and could also be applied in workplaces or shared living accommodations."

Tupper

The findings, therefore, show that a large outbreak can only be prevented with regular monitoring of everyone in the school setting. From these results, the researchers are planning to include more data and expand models to explore further preventative strategies once a positive infection is detected. These models can be used to examine these factors under a classroom environment, but will also be extended to other settings at risk, including public spaces, shared accommodation, or offices.