With tens of millions of people worldwide having been infected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), long-term monitoring efforts have been ongoing to pick up symptoms of long COVID-19. With the onset of vaccination campaigns in many countries, the need to detect adverse effects of COVID-19 has emphasized the need for such surveillance.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

These vaccines were rolled out in late 2020/early 2021. Local reactions to the vaccines include tenderness with the O-AZ and pain with the PB vaccine in 76% and 83% of younger recipients, respectively. Other common side effects were fatigue, headache, and fever. More serious was the vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) seen in rare cases following either the O-AZ or Janssen vaccines.

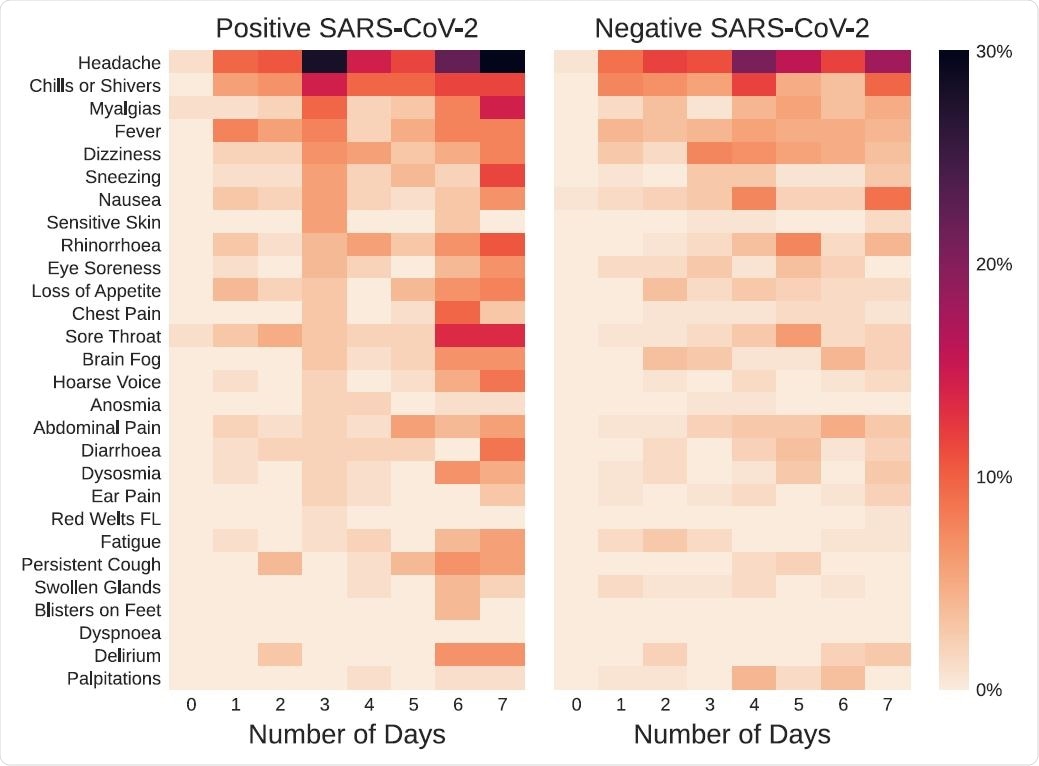

Symptom prevalence and distribution during the first week after the first dose of vaccination, in symptomatic individuals testing positive or negative for SARS-CoV-2. The color bar represents the percentage of symptomatic individuals reporting each symptom.

Numerically, the UK has seen 70 deaths among 395 cases of VITT, out of over 69 million vaccinations, with over 45 million of these being O-AZ. While severe COVID-19 is more common with age, side effects of the vaccine are more common in younger individuals.

There is a need to differentiate symptoms of early infection from those due to vaccination since the former mandates patient quarantine to limit transmission. This may be done by testing every individual with COVID-19-like illness (CLI), but it is cumbersome due to the cost and effort involved.

The current paper aims to differentiate those who have systemic side-effects of vaccination from those who also have breakthrough infections.

What were the findings?

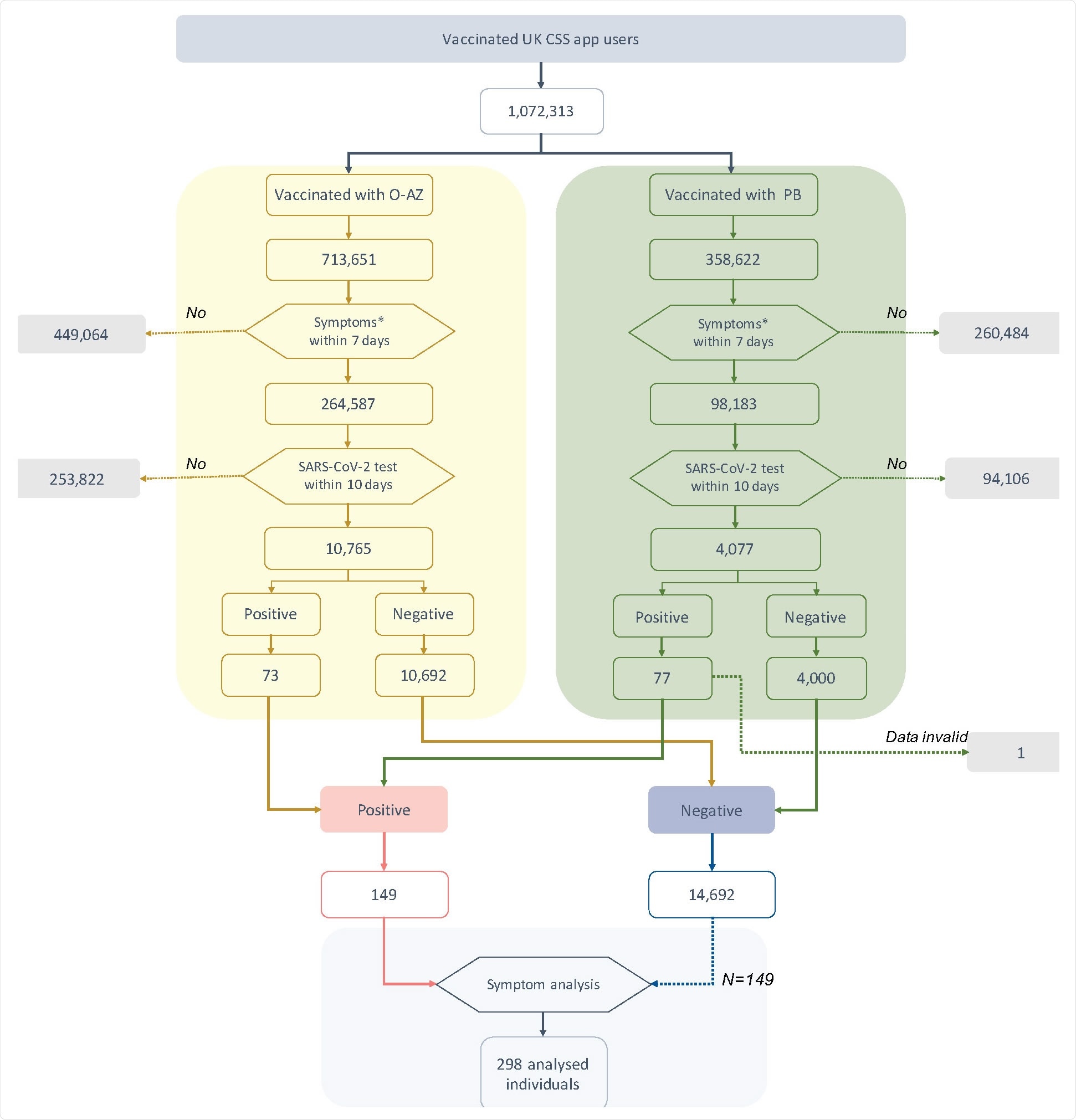

The researchers found that over one million UK CSS app users who had taken either the O-AZ or PB vaccine, one in three, had one or more symptoms soon thereafter. The SARS-CoV-2 test was carried out in 4% of them, with 1% (n=150) eventually being confirmed to have an infection.

This accounted for ~0.7% and 1.9% of the tested groups who had received the O-AZ and PB vaccines, respectively.

Of the tested individuals, numbering ~15,000, a quarter had CLI, of whom less than 2% were positive. In contrast, of the >11,000 who had no symptoms of CLI, 0.8% tested positive, indicating that these symptoms indicate a higher risk of test positivity. In absolute terms, however, the opposite is true since 88 of 150 test positives were missed by the use of symptoms alone.

Some symptoms such as headache and muscle pain increased in prevalence over time irrespective of test positivity. Sneezing and hoarseness increased only in those who tested positive, however. Fever and sore throat were, conversely, increased in the test negatives.

The most prolonged duration of symptoms in the latter category was for alterations in smell and for delirium. However, no formal difference was observed for the duration in positive vs. negative individuals.

Flowchart of individuals included in this study. Symptoms* within 7 days excluded local symptoms related to injection site. SARS-CoV-2 test included both rtPCR and LFAT. Positive and negative refers to self-logged test results.

What are the implications?

The study aimed to develop a workflow that would sort symptoms to predict the risk of infection in symptomatic cases in the early post-vaccination period. This could help direct testing towards the high-risk segment, saving limited resources in low- and middle-income countries.

The scientists admitted that they could not find a reliable distinction between symptoms due to the vaccination and those due to superimposed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The analysis also showed minimal testing among symptomatic vaccine recipients. Even when their symptoms fulfilled the criteria for CLI, only 40% were tested. The reason for the low rate of testing in the face of readily available facilities in the UK is unclear.

Similarly, of the 150 people who had a positive test result, only 40% had CLI, and the rest were tested for reasons other than the presence of such symptoms.

The use of core symptoms as an indicator of testing may miss out on many test positives, suggesting the need to refine the policy in the UK, and widen the testing net.

The fact that symptoms could not clearly demarcate test positives from negatives early in the illness means that this cannot be developed into an algorithm to identify those who should be tested and isolated.

The time of infection in these cases is unknown, though the study criteria ensured that only recent infections were included. However, the infection may have occurred before vaccination since many infections are asymptomatic – and in this case, the study required that all vaccine recipients included be asymptomatic.

The infection may also have occurred during vaccination. However, the severity of the illness is much lower after vaccination than in unvaccinated individuals. Thirdly, vaccination may have induced a sense of false security, which led to riskier behavior and a greater likelihood of infection. This corroborates the findings of some earlier studies.

“In conclusion, post-vaccination symptoms cannot be distinguished with clinical confidence from early SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our study highlights the critical importance of testing symptomatic individuals - even if recently vaccinated – to ensure early detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection and help prevent future waves of COVID-19.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources