Researchers in the United States and Canada have conducted a study showing that the vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna to protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) generate local antibody responses in the salivary gland that are independent of the systemic immune response.

The team found that just one dose of Pfizer-BioNTech’s BNT162b2 vaccine or Moderna’s mRNA-1273 product induced salivary immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies against the COVID-19 causative agent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Interestingly, these antibodies were associated with the secretory component in the salivary gland rather than being derived from blood and entering via the gingival crevicular fluid.

Jen Gommerman from the University of Toronto and colleagues suggest that these secretory IgA antibodies in the saliva may contribute to reducing the person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the medRxiv* server while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

More about the significance of antibodies in saliva

The initial stage of the SARS-CoV-2 infection process begins when the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the viral spike protein interacts with the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the surface of epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract.

Therefore, the immune response in the oral and nasal mucosa represents an important first line of defense. Saliva can provide information about the antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 at these mucosal sites.

Blood-derived antibodies can enter saliva via the gingival crevicular fluid, but local antibody responses, including secretory IgA (sIgA) can also be generated in the salivary glands.

“SIgA exist as IgA dimers that are associated with the secretory component, a proteolytic cleavage product which remains associated with IgA after it is transported across epithelial cells,” explains Gommerman and colleagues.

Salivary viral load positively correlates with COVID-19 symptoms

Studies have recently shown that the saliva of individuals exposed to SARS-CoV-2 contains infectious viral particles and that salivary viral load is positively correlated with COVID-19 symptoms, thereby highlighting the importance of saliva as a proxy for studying the early mucosal immune response.

“The salivary glands themselves express ACE2 and harbor a significant population of IgA-producing plasma cells,” says the team.

The researchers recently showed that IgG, IgA and IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and its RBD are readily detected in the saliva of COVID-19 acute and convalescent patients.

.jpg)

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2—also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19. Virus particles are shown emerging from the surface of a cell cultured in the lab. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, crown-like. Image captured and colorized at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana. Credit: NIAID

However, very little is known regarding whether the current COVID-19 vaccines, which are all administered via the parenteral intramuscular (i.m.) route, can induce immunity in the saliva.

“While these i.m. vaccinations induce a robust systemic IgG response capable of neutralizing SARS-CoV-2, whether they can induce antibodies in the saliva is unclear,” writes Gommerman and colleagues.

What did the researchers do?

The team used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay- (ELISA) based method to analyze salivary antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the RBD among 150 long-term care home residents (LTCH) who received two i.m. injections of either the Pfizer BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine or Moderna’s mRNA-1273 product.

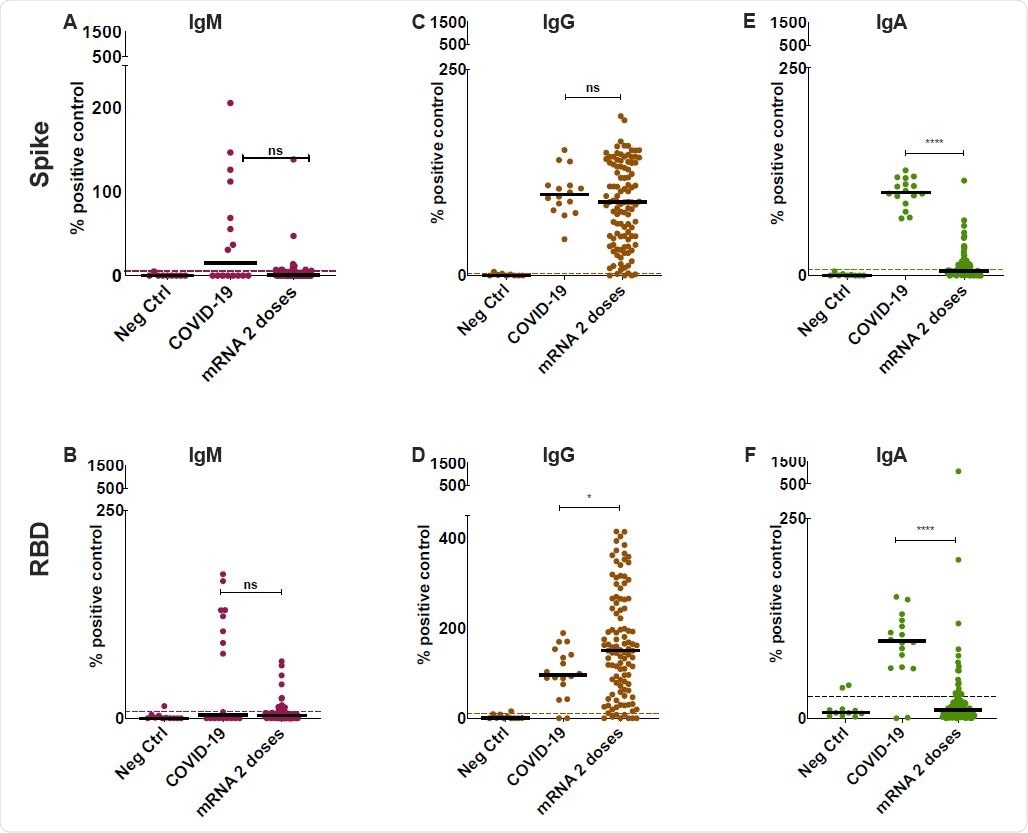

Among participants with no previous history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (n=107), 94% and 41% were positive for anti-spike IgG and IgA, respectively, and 93% and 20% were positive for anti-RBD IgG and IgA.

These anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG and IgA levels correlated well with corresponding levels in the blood, suggesting that the salivary antibodies were at least in part derived from the systemic immune response.

Investing the effects of single vaccine dose

In some countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom, vaccine dose sparing has resulted in delayed delivery of a second vaccine dose.

“As of June 2021, although most LTCH workers had been fully vaccinated, significant sectors of the Canadian population had only been administered a single dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, and the interval between dose 1 vs. dose 2 was extended,” writes the team.

The researchers, therefore, tested whether salivary antibodies could be detected after a single vaccine dose and how long these antibody titers persisted.

The team measured anti-SARS-CoV-2 salivary antibodies over time in samples from a second cohort of 101 healthy adults who received an initial dose of BNT162b2 and a second dose approximately 3 months later.

Detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike and RBD specific antibodies in the saliva of mRNA vaccinated participants. Anti-Spike (A,C,E) and anti-RBD (B,D,F) antibodies were detected using an ELISA-based assay in the saliva of vaccinated participants after two-doses of either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 (n=107 for both combined). COVID-19 controls consisted of saliva collected from acute and convalescent patients (n = 18). These were compared to n=9 individually run negative controls. The positive cutoff (dotted line) was calculated as 2 standard deviations above the mean of a pool of negative control samples (n=51) for each individual assay. Y-axis was set at 1500% for all plots as this was the highest value for measurements in Fig. 2D, allowing for cross-isotype comparison in all cohorts. All data is expressed as a percentage of the pooled positive plate control, calculated using the AUC for each sample normalized to the AUC of the positive control (see Methods). Solid black bars denote the median for each cohort. Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate significance, where ns=not significant, *=p<0.05 and ****=p<0.0001.

The study revealed that 97% and 93% of participants were positive for anti-spike IgG and IgA, respectively, two weeks following the first dose, and that 52% and 41% were positive for anti-RBD IgG and IgA antibodies.

Three months following the first dose, the median levels of salivary anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG had diminished, but two weeks following the second dose, the median IgG levels were either recovered (anti-RBD) or were elevated (anti-spike).

“Thus, two doses are required to maintain anti-Spike/RBD IgG levels in the saliva,” writes Gommerman and colleagues.

The team suspected that vaccination triggered a localized IgA response in the oral cavity

Interestingly, while the levels of anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG in saliva correlated with those observed in serum, this was not the case for anti-spike and anti-RBD IgA.

The team, therefore, hypothesized that the spike and RBD-specific IgA response induced by BNT162b2 vaccination triggered a localized IgA response in the oral cavity.

To test this, the researchers designed an ELISA that would measure secretory component-associated anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the saliva of the vaccinated LTCH participants.

They found that secretory component-associated anti-spike and anti-RBD antibodies could be detected in 30% and 58% of participants, respectively.

When the researchers divided the cohort into those who were positive versus negative for anti-spike or RBD IgA, the secretory component signal was only detected in those who were IgA-positive.

“We conclude that secretory component is associating with anti-Spike/RBD IgA (sIgA),” writes Gommerman and colleagues. “Therefore, a local sIgA response to Spike/RBD is produced in response to vaccination with BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273.”

What might this mean in terms of transmission?

The researchers point out that just a single dose of BNT162b2 has been shown to blunt the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

“Among other mechanisms, protection against transmission could involve an antibody response that engages effector mechanisms (i.e., blocking viral entry and/or engagement of antibody-dependent or complement-dependent cytotoxicity) at the site of infection,” they write.

“We provide evidence of anti-Spike/RBD IgG and sIgA antibodies in the saliva of vaccinated participants that may have the capacity to contribute to reducing person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Gommerman J, et al. A mucosal antibody response is induced by intra-muscular SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.01.21261297, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.01.21261297v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Sheikh-Mohamed, Salma, Baweleta Isho, Gary Y. C. Chao, Michelle Zuo, Carmit Cohen, Yaniv Lustig, George R. Nahass, et al. 2022. “Systemic and Mucosal IgA Responses Are Variably Induced in Response to SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccination and Are Associated with Protection against Subsequent Infection.” Mucosal Immunology, April. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-022-00511-0. https://www.mucosalimmunology.org/article/S1933-0219(22)00001-0/fulltext.