The earliest evidence of a close connection between the lung and the gut in humans described severe lung disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Microbes are fundamental to this cross-talk since they are key to normal and pathological immune responses in both organ systems.

Changes in one system affect the other, which has led to the concept of the "gut-lung axis." In the current pandemic, patients with COVID-19 often have both gut symptoms and respiratory symptoms at the same time. The present study looks into the role of this axis in COVID-19, especially to examine whether this link might be responsible for the severity of the disease in some patients.

Diabetes is a risk factor for severe and fatal COVID-19, and it is related to abnormalities of the gut flora. Such evidence has led to the investigation of the role of the gut-lung axis in predicting the risk of, treating, and preventing severe disease.

The gut-lung axis

The respiratory and gut tissues are formed from the same embryonic tissue and have a similar structure. While they have different functions, both present a physical barrier against external pathogens. Both harbor their own array of commensal microbes that offer a layer of resistance to the active spread of pathogens. They have a mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) which is key to the immune function of the respective tissues. This can provide a basis for the lung-gut interactions in health and disease.

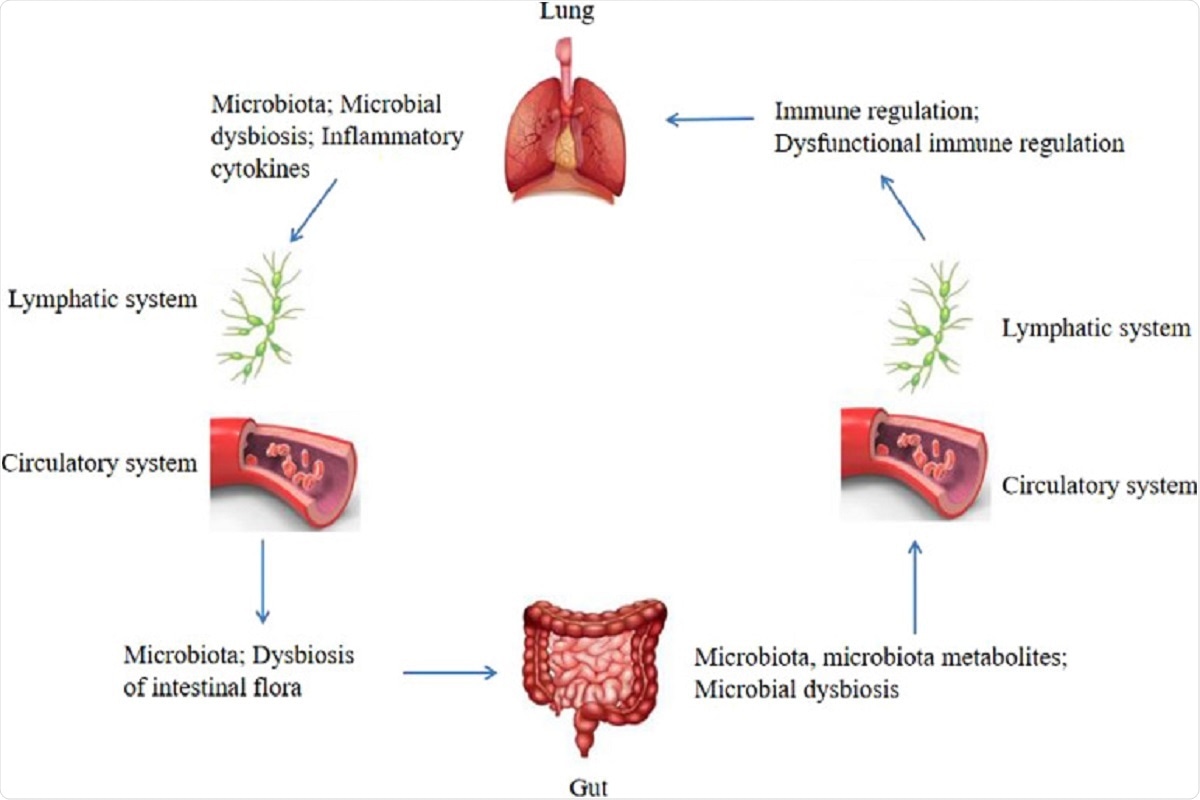

Figure 1: Bidirectional gut-lung axis. The gut microbiota and microbiota metabolites can regulate the lung immune through the lymphatic or circulatory systems, when the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota are changed, which termed microbial dysbiosis, can affect the lung immune through the lymphatic or circulatory systems. Similarly, the lung microbiota may also affect the gut microbiota through the lymphatic or circulatory systems, the dysbiosis of the intestinal flora can be caused by the lung microbial dysbiosis and inflammatory cytokines through the lymphatic or circulatory systems.

Microbiota and the gut-lung axis

The gut microbiota and the gut form a symbiotic whole, with the microbial metabolites benefiting the host in several ways and forming parts of multiple signaling and feedback loops.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate and propionate produced by certain bacteria such as Bacteroidetes or Clostridium have positive anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory functions on the host. Similarly, desaminotyrosine, also produced by some microbes, stimulates a type I interferon response that prevents influenza in mice.

An imbalance in the gut microbiome (gut dysbiosis) can promote the growth of opportunistic pathogens, causing altered metabolism and immune responses, leading to inflammation. Gut dysbiosis has been linked to asthma and cystic fibrosis. In mice, influenza was associated with changes in gut microbial species. Again, after administering lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in mice, with a resulting disturbance in lung microbiota, the gut flora also showed a corresponding disruption as bacteria moved from the lungs into the systemic circulation. This underlines how microbes mediate in part the gut-lung interactions and how dysbiosis in one arm of this axis affects the other.

Dysbiosis in COVID-19

Dysbiosis has been identified in individuals with COVID-19, including many bacterial pathogens. Some scientists suggest that certain Clostridium species are more abundant in severe COVID-19, while conversely, Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii is reduced.

The increased severity of COVID-19 in the elderly may be related to the reduction in gut flora diversity, with lower levels of 'good' bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, which has a protective role. These findings suggest that dysbiosis correction using prebiotics and probiotics is essential in severe COVID-19.

Common mucosal immunity

Scientists have highlighted a mouse experiment where the distribution of transferred donor B cells from the gut lymph nodes extended to almost every mucosal tissue. Conversely, B cells from peripheral lymph nodes remained peripheral in their distribution. This is explained as the activity of all mucosal surfaces in the body as one organ protecting against foreign pathogens. It may be the mechanism by which vaccination at one mucosal site protects other mucosal interfaces from infection.

The gut and lung appear to be one such interlinked mucosal immunity system because of their gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). The former contains an abundance of innate and adaptive immune cells. Its rich vascular supply carries both immune cells and immune factors to the BALT to promote resistance to respiratory infections. Again, a mouse experiment has shown that injected lymphoid cells in the gut were later found in the lung after activation, demonstrating that both lymph and blood connect these sites when one is activated.

The question of the hyperinflammatory reaction characteristic of severe COVID-19 is also addressed in these terms by the researchers. The intense inflammation may damage the protective intestinal mucus layer and increase the permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier. This causes immune cells to be recruited from outside the gut, enhancing tissue inflammation and damage. These cells may travel to the BALT next, triggering lung inflammation. This may be one reason for the observed link between gut symptoms and increased severity of COVID-19. This hypothesis suggests that the role of such symptoms in predicting the risk of serious respiratory distress in COVID-19 needs to be examined.

ACE2 and the gut-lung axis

Angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) modulates the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) fundamental to cardiovascular, renal, and pulmonary blood flow in health and disease. It is also the receptor through which SARS-CoV-2 gains entry to the host cell, present on lung cells and in the heart, blood vessels, brain, kidney, and gut.

ACE2 is related to the transport of amino acids in the gut and immune homeostasis. With SARS-CoV-2 infection, ACE2 is downregulated, which could cause gut dysbiosis and thereby lead to lung inflammation.

What are the implications?

The role of gut dysbiosis in lung and gut homeostasis indicates the need to explore prebiotics and probiotics, including fecal transplants, as a mode of mitigating the severity of COVID-19. Secondly, the need to treat the whole body in severe COVID-19 is revealed, as the common mucosal immune system concept shows the intimate relationship between the body's mucosal sites.

Journal reference:

- Zhou, D., Wang, Q. and Liu, H. (2021) "Coronavirus disease-19 and the gut-lung axis", International Journal of Infectious Diseases. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.013.