The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has baffled scientists with its apparently random pattern of severe disease. Caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), COVID-19 has a mortality rate of 1% in most developed nations, thereby suggesting that most infections are asymptomatic or mild.

The occurrence of persistent disability after SARS-CoV-2 infection has disturbed many researchers. A recent study published on the preprint server medRxiv* discusses the rate of changes in peripheral blood white cells (WBCs) in individuals who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection, and how these differed from alterations seen with other mild respiratory infections. The investigators found short-lived changes in various cell subsets in circulation that differentiated mild COVID-19 from other conditions.

Background

SARS-CoV-2 infection is known to cause atypical WBC changes. Rather than the expected acceleration of neutrophil-monocyte release from the bone marrow, without much impact on lymphocyte function or numbers, SARS-CoV-2 is associated with a frequent occurrence of early and severe lymphopenia. In fact, this finding is a mortality marker with COVID-19.

T-cell loss during COVID-19 is attributable to the death of these cells within the secondary lymphoid organs. Alternatively, this loss of T-cells could be attributed to their influx into the lungs or other organs following their recruitment. It is noteworthy that this recruitment is unnecessary and potentially harmful.

Other changes in severe COVID-19 include hypergranularity and nuclear changes in monocytes and neutrophils. These changes have been linked to the premature release of these cells from the bone marrow, thus affecting their maturation.

The many reports of long COVID-19, which refers to persistent health issues following recovery from the acute infection, indicate a broad spectrum of symptoms including easy and severe fatigability, pain, breathlessness, and increased risk of re-admission to the hospital for respiratory problems. The effect of the infection on immunity in mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 is the focus of the current paper.

Study findings

The current study included people with mild respiratory symptoms who had a prior positive reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for COVID-19, or were seropositive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, as well as those who did not – either seronegative or a negative test.

The researchers found that activated CD4 and CD8 T-cells were increased after stimulation with one or more of the viral antigens; namely, the membrane glycoprotein (M), the nucleocapsid (N) or the spike (S), at 1-9 months after mild COVID-19. The CD4 responses were comparable to all antigens and peaked at 1-3 months.

At this point, but not at 6-9 months, CD4 but not CD8 T-cells were markedly higher in COVID-19 recovered patients than in those who had recovered from other respiratory infections.

Immune activation can linger after recovery from severe infections. This is thought to cause prolonged weakness or tiredness in recovered patients. In the current study, evidence of prolonged inflammation was found, even though almost all participants had recovered clinically within a month of infection.

Biomarkers of continuing inflammation included C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in all seropositive individuals at 1-3 months. However, at 6-9 months, there was no difference between these participants and those with other respiratory infections.

Polyclonal activation of T-cells was stronger with COVID-19 patients than in the other group, and this trend continued to be observed in the later samples. This finding suggests the occurrence of slight but definite changes that may characterize the effect of COVID-19 in activating T-cells in contrast to other respiratory infections.

While the total number of CD4 and CD8 T-cells remained similar in both groups up to 9 months, the T-cell phenotype showed differential markers. For instance, at 3 months from infection, natural killer (NK) cells were reduced, whereas regulatory T-cells increased at 1-3 months. These changes reverted to the profile found in other respiratory infections by 6-9 months.

The central memory CD4 T-cells and terminally differentiated CD8 T-cells increased in COVID-19 patients at 1-3 months from symptom onset. Comparably, the presence of these cells was indistinguishable from the response to other respiratory infections at 6-9 months. Other T-cell subsets showed no differences between the two groups.

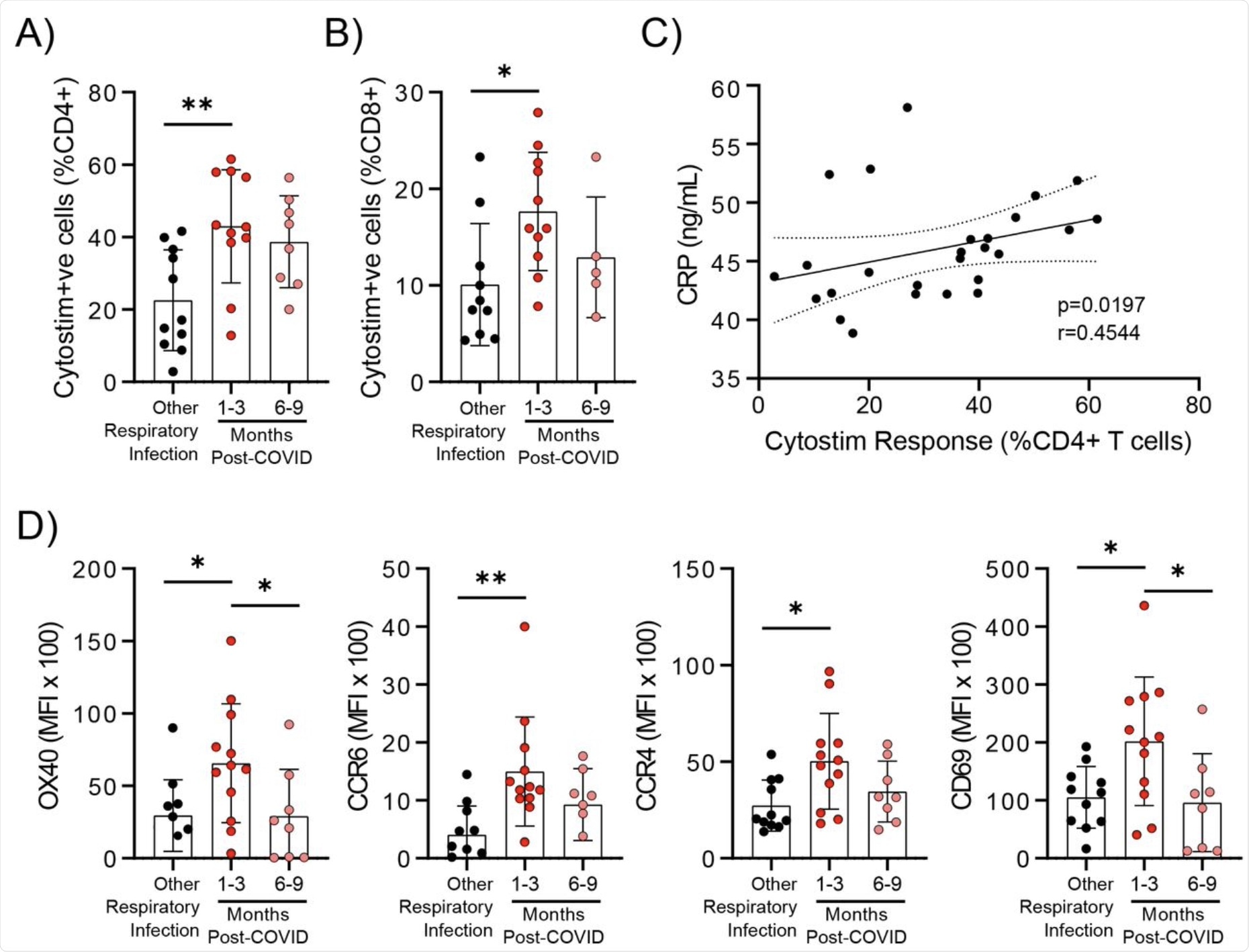

Evidence of prolonged T cell activation after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. The polyclonal activator Cytostim was used to measure T cell responses. COVID-19 seropositive individuals had a higher proportion of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) activated T cells 1 to 3 months after infection compared to seronegative individuals after other respiratory infections. C) The number of CD4+ T cells that responded to polyclonal stimulation correlated with CRP in COVID-19 seropositive individuals. D) Activation markers on the Cytostim-responsive CD4+ T cells OX40, CCR6, CCR4, and CD69 were higher 1-3 months after COVID-19 infection compared to after other respiratory infections. Each participant is indicated by a single data point: other respiratory infection n=7-11; 1-3 months post COVID-19 infection n=11-12; 6-9 months post COVID-19 infection n=5-8. Multiple group comparisons in A-B and D were tested using Welch’s One-Way ANOVA and Games-Howell post-hoc test; bars are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Data in C was assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Evidence of prolonged T cell activation after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. The polyclonal activator Cytostim was used to measure T cell responses. COVID-19 seropositive individuals had a higher proportion of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) activated T cells 1 to 3 months after infection compared to seronegative individuals after other respiratory infections. C) The number of CD4+ T cells that responded to polyclonal stimulation correlated with CRP in COVID-19 seropositive individuals. D) Activation markers on the Cytostim-responsive CD4+ T cells OX40, CCR6, CCR4, and CD69 were higher 1-3 months after COVID-19 infection compared to after other respiratory infections. Each participant is indicated by a single data point: other respiratory infection n=7-11; 1-3 months post COVID-19 infection n=11-12; 6-9 months post COVID-19 infection n=5-8. Multiple group comparisons in A-B and D were tested using Welch’s One-Way ANOVA and Games-Howell post-hoc test; bars are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Data in C was assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Monocytes showed an interesting pattern of change at 1-3 months. Classical monocytes are found at higher levels only during acute infection and, in this study, their number was not above normal. However, at 1-3 months, CCR2 receptor expression was low on other monocyte populations, perhaps because the cells with the highest expression of this receptor had left the circulation for the tissues.

Conversely, the CX3CR2 chemokine receptor is typically found at higher levels on intermediate and non-classical monocytes, as it is a recruitment signal and associated with tissue repair. This marker was low at 1-3 months, thereby indicating that these cells had left the peripheral blood. The reduction in CX3CR2 expression is closely correlated with the proportion of S protein-specific CD4 T cells.

M-specific CD8 T-cells were linked to HLA-DR expression on non-classical monocytes. Polyclonal T-cell activation markers were not found in association with the activation of myeloid series white cells, thus suggesting that these changes occurred as a result of the specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response rather than as part of the generalized T-cell activation response to this virus.

The integrin marker CD11b was increased for a time on monocytes at 1-3 months from the onset of symptoms.

These changes indicate a systemic activation of the immune response, though transient, which may alter the pattern of migration in monocytes following mild infection with SARS-CoV-2. Either baseline inflammation levels are increased, or the immune response to the virus involves these monocytes as well.

Implications

The current study indicates that even after mild COVID-19 and without long COVID, individuals may have high immune activation and systemic inflammation for 1-3 months after clinical resolution. The percentages of memory CD4 and CD8 T-cells that react to the S, M, and N antigens are similar to those previously reported for severe or moderate COVID-19.

In other words, memory cell responses do not correlate with clinical phenotype.

For the first time, non-specific T-cells were activated by Cytostim stimulation in patients recovering from COVID-19. The activation markers were higher in stimulated cells following mild COVID-19 than in the other respiratory infection group, with some remaining high at 6-9 months.

Perhaps the CD4-activated T-cells at 1-3 months after COVID-19 may be a response to high circulating IL-6 or other promoters of T-cell activation. Alternatively, these cells may be able to mount a faster and more robust response when activated.

The Tregs may be involved in preventing tissue damage during acute respiratory infection; however, the elevation was observed in the convalescent phase.

“Collectively, these data provide evidence that mild, and in some individuals even asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections, can lead to sustained immune activation after resolution of symptoms, which is not observed in response to other mild respiratory infections. Whether this immune activation is more pronounced in patients with long-COVID, or more serious infections, remains to be seen.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Kennedy, A. E., Cook, L., Breznik, J. A., et al. (2021). Lasting Changes to Circulating Leukocytes in People with Mild SARS-Cov-2 Infections. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.09.25.21264117. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.25.21264117v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Kennedy, Allison E., Laura Cook, Jessica A. Breznik, Braeden Cowbrough, Jessica G. Wallace, Angela Huynh, James W. Smith, et al. 2021. “Lasting Changes to Circulating Leukocytes in People with Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infections.” Viruses 13 (11): 2239. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13112239. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/13/11/2239.