The study reaffirms current recommendations for essential workers in the food manufacturing sector from the current international (U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], and European Union-OSHA, EU-OSHA), domestic (U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA], OSHA), and food industry-standard guidance for managing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and SARS-CoV-2 transmission in essential workers in the food manufacturing sector. These include symptom screening, physical distancing, mask use, enhanced surface disinfection, and handwashing practices.

Study: Controlling risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in essential workers of enclosed food manufacturing facilities. Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shtuterstock.com

Study: Controlling risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in essential workers of enclosed food manufacturing facilities. Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shtuterstock.com

Introduction

For the maintenance of global food supply chains and consumer food security, it is essential to protect the health of these workers during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, the relative importance of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, specifically in the food industry, has not been quantified.

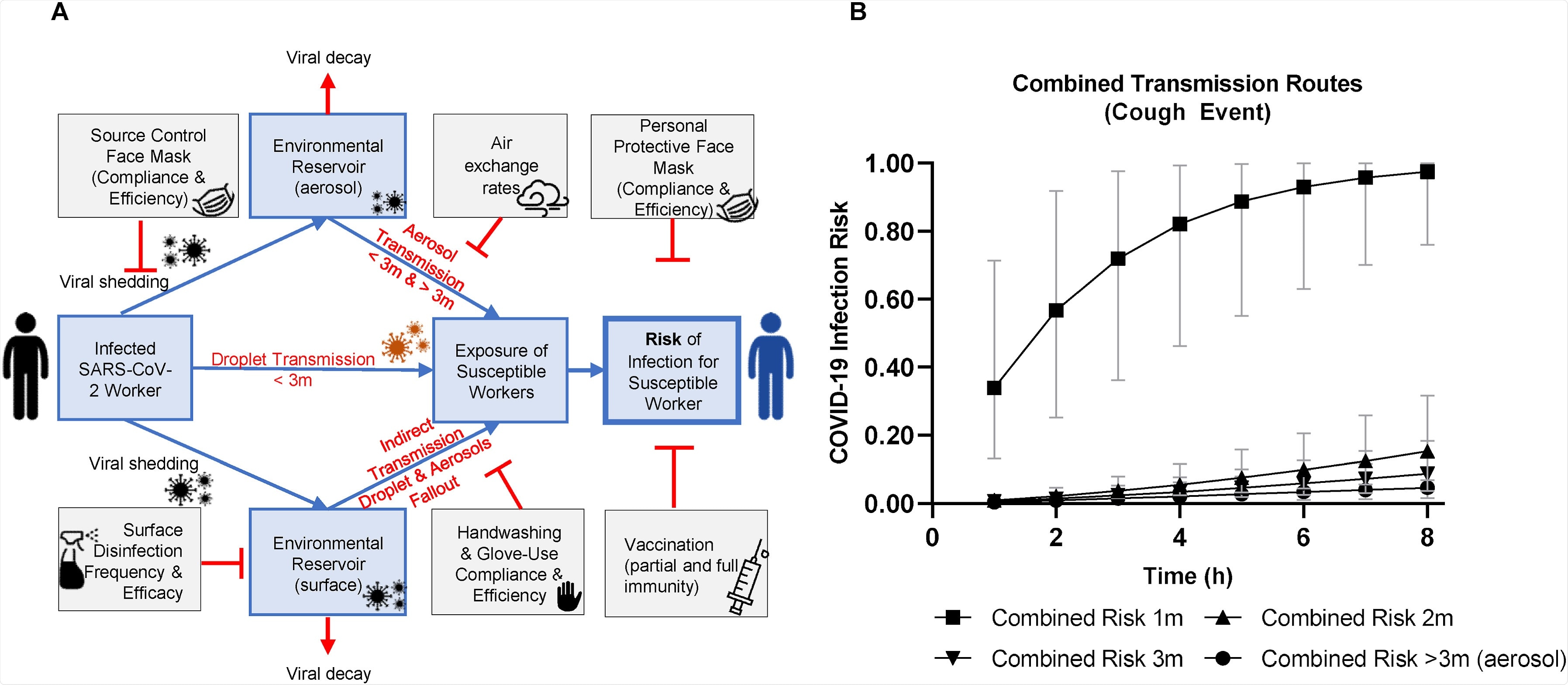

Viral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 may occur directly through exposure to infected droplets and aerosol, as well as indirect transmissions by touching contaminated fomite surfaces.

During close contact of fewer than 2 meters, susceptible individuals may be infected through droplets, which are large virus-containing particles that have a diameter of more than 100 micrometers (µm) by respiratory events such as coughing or sneezing.

Comparatively, aerosols are small droplets, and exposure to these droplets can occur in close contact or at further distances of up to 9 meters. These particles are secreted during all respiratory events, especially during breathing and speaking.

Indirect transmission by exposure to contaminated fomite surfaces is detected on surfaces in various settings. Previous studies have found the presence of SARS-CoV-2 to remain on fomite surfaces for up to 72 hours. Because food workers share workstations and tactile events occur, it is also important to investigate the role of fomite-mediated transmission in a food production and processing setting.

While studies suggest physical distancing, mask use, handwashing, and surface disinfection as effective measures against SARS-CoV-2 transmission, no evaluation of the health risks associated with direct and indirect transmission pathways has been conducted. This type of evaluation would provide insight into the efficacy of infection control strategies within food manufacturing facilities.

In the present study, the researchers employ a stochastic quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) model to quantify the impact of risk reduction measures for controlling SARS-CoV-2 transmission (droplet, aerosol, fomite-mediated) among essential workers in an indoor fresh fruit and vegetable manufacturing facility. The measures addressed in the current study include physical distancing, masking, ventilation, surface disinfection, hand hygiene, and vaccination.

Study findings

The QMRA model structure varies according to the viral transmission pathways, workers’ shift, distance of contact (close/distant), breathing event, and commonly-used infection control interventions. To estimate the SARS-CoV-2 infection risks among essential food workers, the authors investigated the relative contribution of each transmission route (aerosol, droplet, fomite) by the distance traveled for each size class of expelled infectious particles for 1 hour and cumulative 8-hour exposures of SARS-CoV-2 in enclosed food manufacturing facilities with a coughing infected worker.

The researchers found that the infectious particle spread was influenced by distance, with the droplet transmission contributing the largest dose of 90% with the dominant transmission mode at 1 meter. Close contact aerosols and droplet exposures predominated the infection risks.

While studying the impact of individual interventions targeting combined risk, the authors demonstrated that the physical distancing of 2 meters and beyond provided the greatest relative reduction in infection risk. Additionally, physical distancing maintained with donned masks resulted in a greater risk reduction as compared to when the distance or masks were used alone., except for when N95 respirators were employed.

Importantly, the researchers found that full vaccination reduced the infection risk by 92%. Furthermore, bundled interventions that included physical distancing of 2 meters, universal mask-wearing, and at least 2 air changes per hour (ACH), combined with hourly handwashing and surface disinfection twice per shift, reduced the risk to less than 1% for an 8-hour cumulative exposure.

Conclusions

The current study uses mathematical modeling to find that workers in enclosed food manufacturing facilities are at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection from close contact transmission as a result of exposure to large droplets and small aerosol particles than fomite transmission. Thus, some of the strategies to protect workers that must be adopted include physical distancing, universal mask use, and room air changes, followed by surface disinfection to reduce fomite transmission and handwashing.

Vaccination is also an effective infection control measure, particularly when combined with these existing food industry standards, as it reduced the infection risk by 92%.

The current work advances evidence-based support for effective risk mitigation strategies currently implemented by the food industry. While the model here was designed for an indoor food manufacturing setting, the researchers suggest that it can be readily adapted to other indoor environments and infectious respiratory pathogens.

Journal reference:

- Sobolik, J. S., Sajewski, E. T., Jaykus, L., et al. (2021). Controlling risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in essential workers of enclosed food manufacturing facilities. Food Control. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108632.