I trained as a physical chemist and wanted to apply myself to an important real-world problem. Neurodegenerative disease was an area where I felt I would be able to make a difference. The latest research has been made possible by over 10 years of work by myself and many others.

During this time we have gradually worked our way from being able to understand the processes that are important in neurodegenerative diseases first in the test tube and then in increasingly complex systems, such as cells and lab animals. Now we have for the first time been able to use the techniques we developed during this period to gain new insights into the disease directly from using patient data.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), currently more than 55 million people are living with dementia worldwide with Alzheimer’s disease contributing to 60-70% of these cases. Why is Alzheimer’s disease so common in today's world and why is new research into this disease critical?

We are getting better and better at managing other diseases often associated with age, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, and therefore dementia is gaining increasing attention.

We have not yet been able to develop effective treatments for the majority of dementias. Improving our understanding of these diseases will enable us to become better at designing drugs against them.

Image Credit: PopTika/Shutterstock.com

Despite Alzheimer’s disease having such a devastating effect on people worldwide, what causes its progression was unknown until now. Why has research into the mechanisms behind Alzheimer’s proven challenging?

It is a complicated process, likely involving many different factors. Research is further complicated by the fact that the disease takes decades to develop in humans. Such a long timescale is generally not feasible to reproduce in lab experiments, like lab animals or in the test tube, so they are often not great models of disease.

Can you describe how you carried out your latest research into Alzheimer’s disease? What did you discover?

We developed a mathematical model that allows us to analyze patient data, from many different methods of measuring disease progression, and thereby figure out what the most important mechanisms driving disease progression are. Being able to analyze patient data directly avoids the above-mentioned issues, but was previously not possible, because we had neither the right mathematical models nor detailed enough patient data.

We found that aggregates multiply exponentially, meaning one aggregate becomes two aggregates after a certain amount of time, which then becomes four after the same amount of time has passed again, then 8, and so on. It is this exponential multiplication step within brain regions that controls the speed of progression, rather than the spread of aggregates from one region to another.

Most research into Alzheimer’s disease has relied heavily on animal models but for your research you used post-mortem brain samples as well as PET scans from living patients. What were the advantages of using human data compared to animal models?

Lab animals are great for answering certain questions about disease. However, Alzheimer’s takes decades to develop in humans. Such a long timescale is generally not feasible to reproduce in lab animals, so they are often not great models of disease.

Ultimately, using human data wherever possible and lab animals where not, is likely the best strategy.

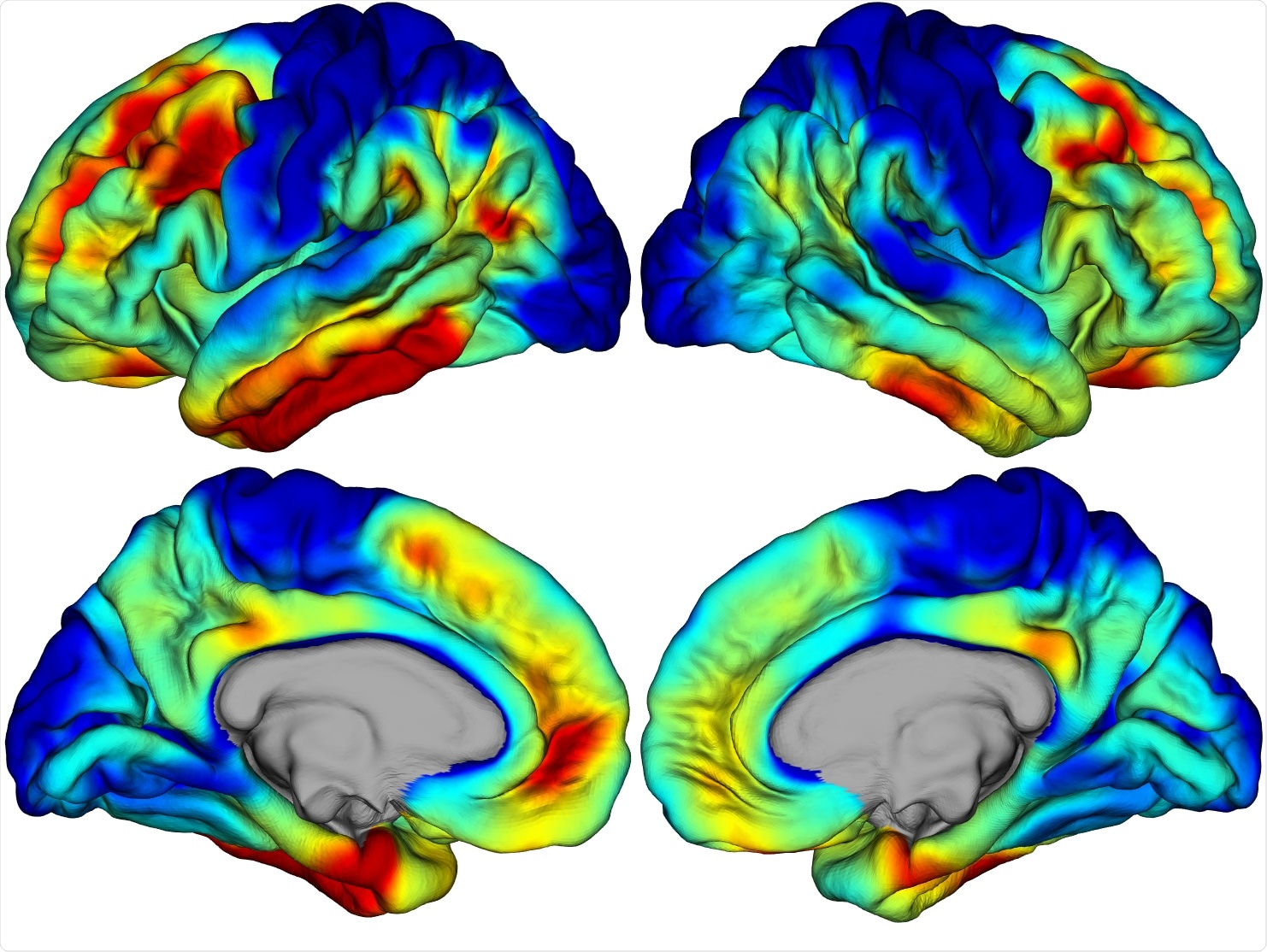

Image Credit: 3D rendering of a PET brain scan to quantify the amounts of tau protein aggregates. Credit Prof Keith Johnson and Justin Sanchez, Massachusetts General Hospital

How could your research also help in the development of new potential treatments?

The better our understanding of the mechanisms of disease the more likely we are to be able to develop drugs against it. We hope that the new insights into Alzheimer’s disease in this work, and the new approach of analyzing data more generally, will contribute towards improving our understanding of disease.

Do you believe that your research could also be used to help us better understand other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's?

My mathematical models are aimed at helping us better analyze human data to get insights into disease mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases in general.

Parkinson’s disease, as well as other rarer forms of dementia, should be amenable to this approach.

What are the next steps for you and your research?

Application of my mathematical models to other neurodegenerative diseases, and to better understand the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease, are projects we are currently undertaking. Much is still unknown in this space and being able to analyze human data in a way that gets at the underlying mechanisms of disease is an exciting prospect with transformational potential.

Where can readers find more information?

Popular science article I wrote about the work: https://theconversation.com/alzheimers-our-research-sheds-light-on-how-the-disease-progresses-in-the-brain-170683

The scientific paper: https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/sciadv.abh1448

About Dr. Georg Meisl

Dr. Georg Meisl is an Austrian chemist and biophysicist working at the University of Cambridge where he uses chemistry, physics, and mathematics to develop new approaches for answering important biological questions.

He started his work as a researcher of neurodegenerative diseases in 2011 and has since worked at the University Hospital in Zurich, at the University of Sydney, at Lund University, and been a Research Fellow at Sidney Sussex College Cambridge. He has co-authored over 70 scientific publications in this space and developed publically accessible software to allow his models to be used by experimental researchers.