Several studies have reported that cardiac complications are associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by the infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). More specifically, heart failure, cardiac injury, and arrhythmias have been observed in individuals diagnosed with COVID-19.

One unusual feature that has been observed in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 is bradycardia, which is a slow heart rate or the lack of an increase in heart rate with body temperature. Furthermore, sinus bradycardia, ventricular tachycardia (VT), or ventricular fibrillation (VF) have been reported in many COVID-19 patients around the world. Inflammatory damage due to the release of cytokines could be responsible for the cardiac involvement with COVID-19.

Study: Occurrence of relative bradycardia and relative tachycardia in individuals diagnosed with COVID-19. Image Credit: BallBall14 / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

Commercially available wearables have been found to be useful in the early detection of COVID-19 and for monitoring symptoms. In fact, resting heart rate (RHR) data from Fitbit devices have been used to study the long-term changes that occur after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

In COVID-19 patients, a rise in RHR typically occurs soon after symptom onset. The term ‘relative’ is used to indicate that the increase or decrease in RHR is relative to the baseline value of the individual and not necessarily above or below the clinical threshold guideline.

In COVID-19 patients, RHR appears to exhibit a dip that is otherwise referred to as transient relative bradycardia that is followed by a second elevated RHR peak. This second increase in RHR has been found to remain elevated for up to 79 days from symptom onset with a dip in between.

In a new study published on the preprint server medRxiv,* researchers from Fitbit assess and compare the resting heart changes in individuals with severe, mild, or asymptomatic COVID-19 and individuals diagnosed with seasonal influenza. The researchers also analyzed heart rate variability, respiratory rate, as well as the variation of both of these health parameters with time.

About the study

Recruited participants from both the United States and Canada provided information on whether they were diagnosed with COVID-19 or the flu, the date of their test, symptoms, the date when their symptoms started, and, for COVID-19 patients, the severity of the disease. Additional information about the age, sex, body mass index, and information on underlying conditions of the participants was collected.

RHR data was collected from the participants through the use of Fitbit devices. The time variation of the RHR data was calculated 14 days before the onset of symptoms to 180 days post-onset of symptoms. Variations in RHR with the time of the year were also calculated. Finally, the respiratory rate was calculated.

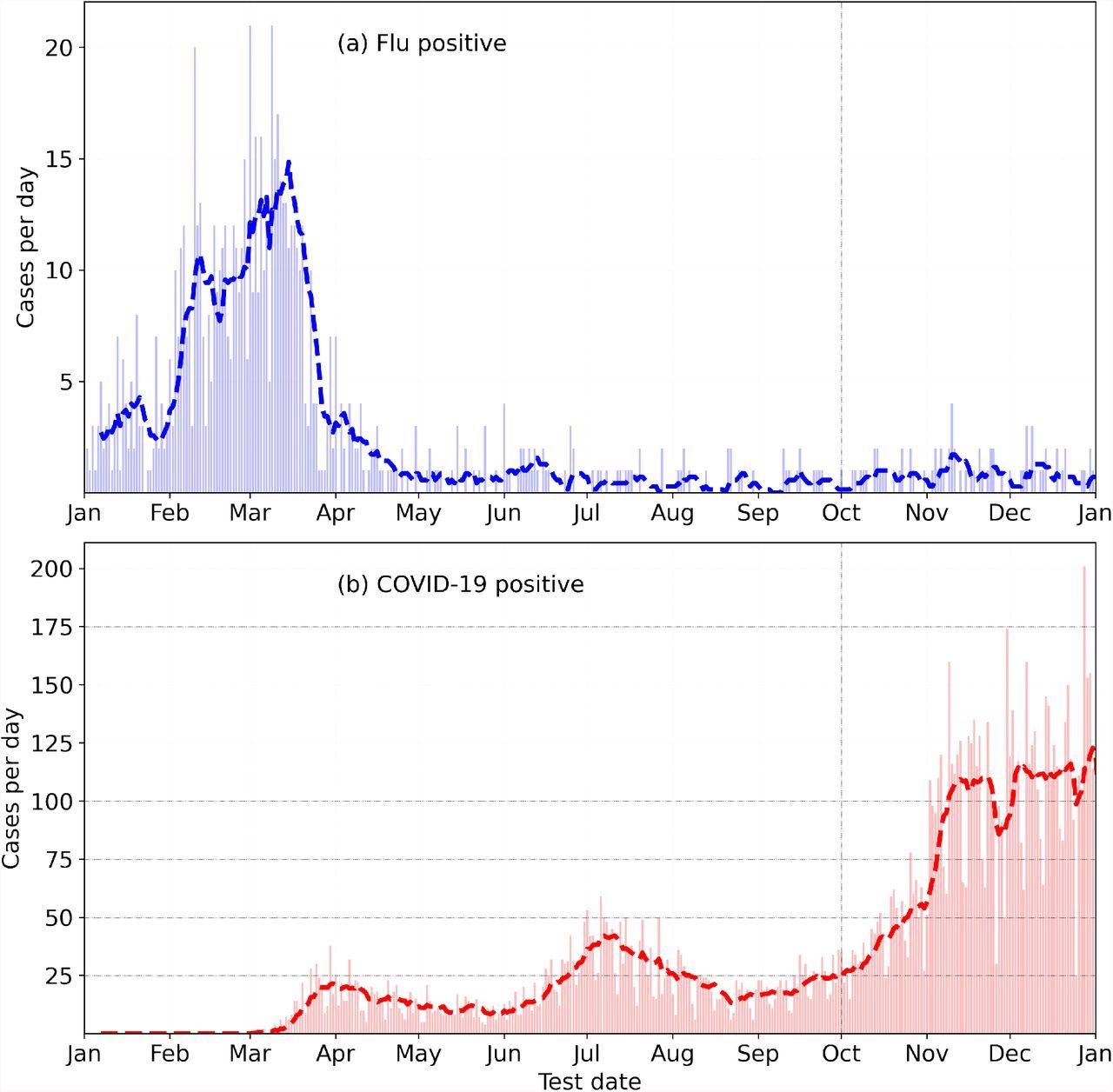

Incidence of Flu (top) and COVID-19 (bottom) in the year 2020, from the Fitbit COVID-19 survey.

Study findings

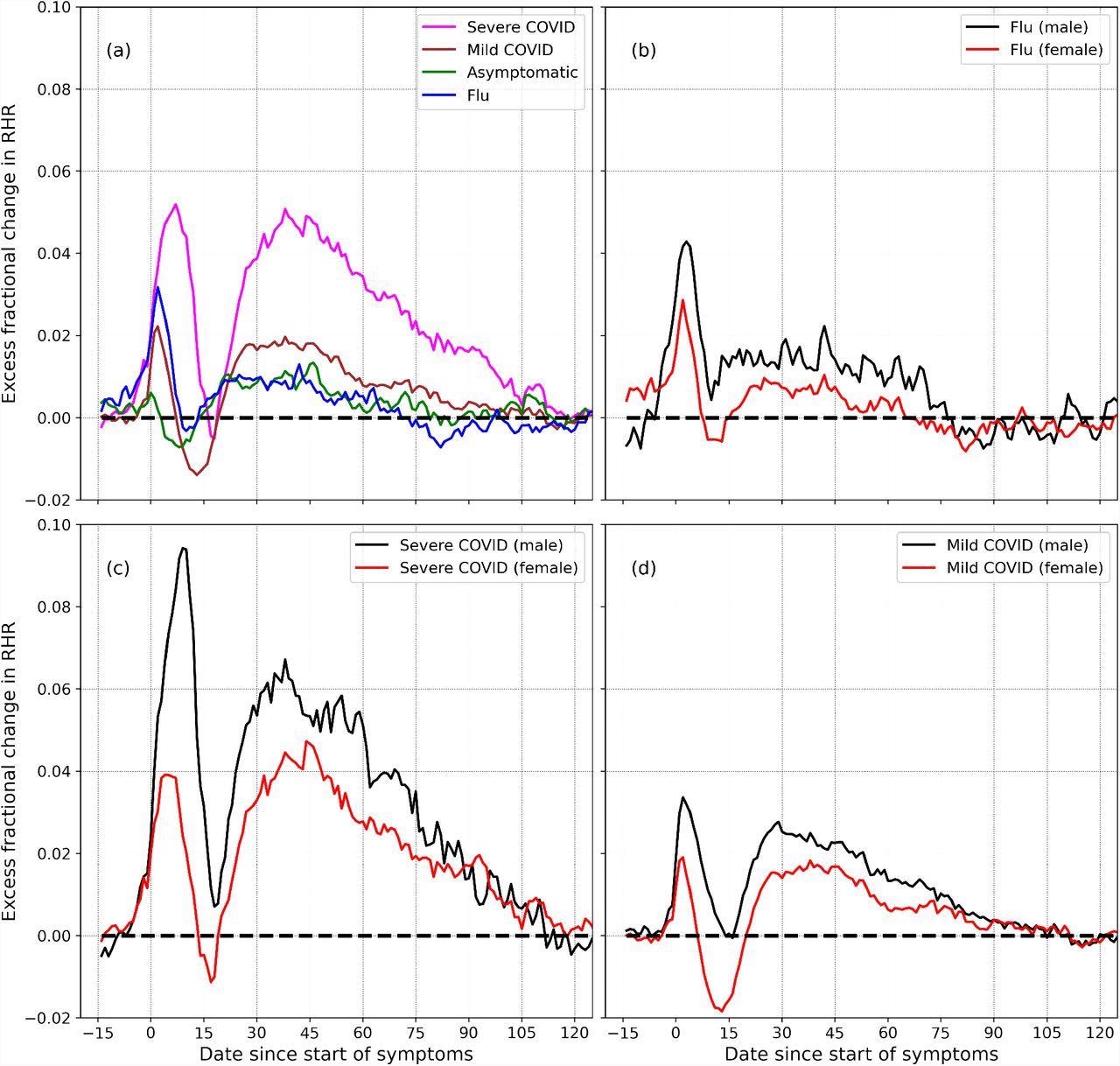

The results indicate that both COVID-19 and the flu show result in three distinct phases following the onset of symptoms. In the first relative tachycardia phase, which occurs during the initial onset of symptoms, RHR is elevated above normal and reaches a peak value. The peak value was found to be higher in males, along with those with mild and severe cases of COVID-19.

Thereafter, RHR decreases and reaches a minimum value that is referred to as the relative bradycardia phase. The minimum value is lower in females and more negative in the case of mild COVID-19 cases. Following this, RHR again reaches a second maximum value that is also higher in males as compared to females.

Excess fractional change in RHR (Δξ), variation with severity and sex: (a) shows Δξ for severe, mild, and asymptomatic COVID-19, as well as flu. (b) shows Δξ for male and female individuals diagnosed with flu. (c) and (d) show Δξ for male and female participants, for the cases for severe and mild COVID-19 respectively.

The relative bradycardia phase was also associated with elevated heart rate variability, while the second relative tachycardia period was associated with lower heart rate variability. The respiratory rate is reported to be independent of the tachycardia or bradycardia phase, in which it increases during the onset of symptoms then decreases sharply and returns to normal.

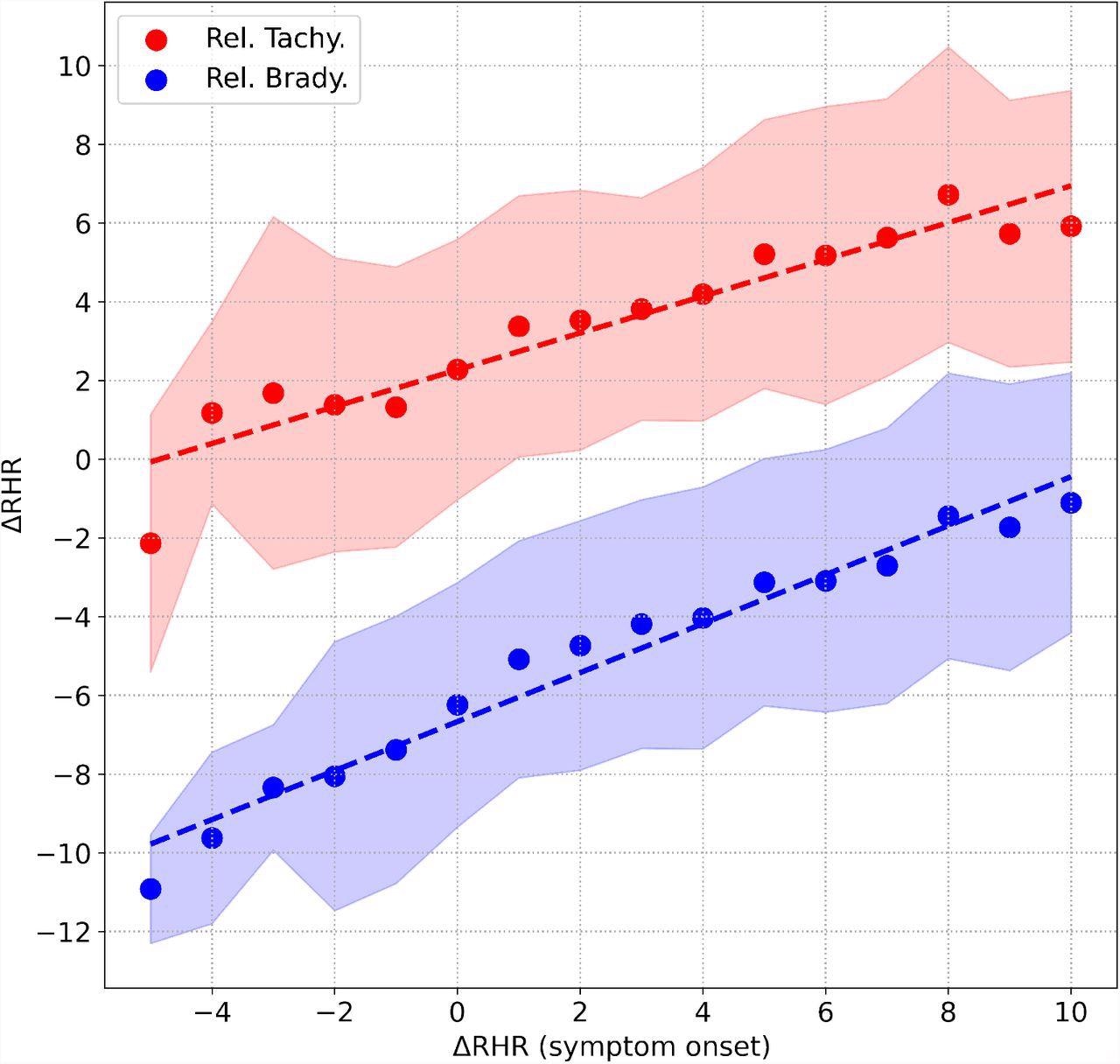

Correlation between the peak value of ΔRHR measured during symptom onset, and (i) peak value of ΔRHR in the second relative tachycardia window shown in red, (ii) minimum value of ΔRHR measured in the relative bradycardia window shown in blue. The shaded areas represent the 1 standard deviation range.

Conclusions

Taken together, the current study demonstrates that the relative tachycardia at symptom onset is due to the increase in RHR. Relative bradycardia is reported a few days after the onset of symptoms when RHR decreases.

Thus, it is important to be aware of the transient relative bradycardia phase, as certain COVID-19 medications such as Remdesivir have been reported to cause bradycardia.

Limitations

The current study had certain limitations, including the fact that the medications taken by patients diagnosed with COVID-19 or flu and their impact on heart rate were not available. Second, data on the start date of symptoms, symptoms, and their severity was collected from a survey and could not be identified separately. A third and final limitation is that the study assumed that the participants were healthy before getting diagnosed with COVID-19 or flu.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources