During the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the speed with which COVID-19 vaccines were developed was impressive. Although the inequitable global SARS-CoV-2 vaccine distribution and the emergence of immune-evasive viral variants posed a threat to vaccine efficacy, the COVID-19 vaccines have saved several lives.

The anti-COVID-19 vaccine sentiment partly fueled by coordinated disinformation campaigns has resulted in low vaccine uptake in several countries, leading to adverse economic and health implications. Although the option to refuse vaccination is sometimes framed as an individual's freedom to choose, such arguments overlook the possible disadvantages to the larger community that result from low vaccine uptake.

Non-vaccination is predicted to increase disease transmission among unvaccinated subpopulations. Yet, since infectious illnesses are communicable, non-vaccination also increases the risk for vaccinated groups when vaccines provide only partial protection. Furthermore, because SARS-CoV-2 has an airborne transmission trait, short-range physical mixing of persons from vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts is not required for disease transmission across groups.

About the study

The goal of the present study was to evaluate how the mixing of COVID-19 unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals affected the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the vaccinated people.

The researchers built a simple susceptible–infectious–recovered compartmental model of COVID-19 with two correlated subpopulations: vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. In order to better understand the implications of the interplay between these two populations, the researchers replicated the interaction between vaccinated and unvaccinated subpopulations in a substantially vaccinated community.

The team established a variety of mixing patterns between vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts, varying from random mixing to complete assortativity (like-with-like mixing), where people only interact with those who have had an identical vaccination status. The researchers investigated the dynamics of an epidemic inside each subgroup and throughout the entire population. They compared subpopulation contributions to the epidemic magnitude and risk estimations. Then, they analyzed the influence of mixing unvaccinated and vaccinated subjects on projected disease dynamics.

Results

The study results demonstrated that despite its simplicity, the present model provided a graphical representation of the assumption that even with highly efficient COVID-19 vaccines and high vaccination coverage, a significant percentage of new cases will occur in vaccinated people. This indicated that rates, rather than absolute numbers, were the reasonable metric for proffering the impact of vaccination. However, the researchers discovered that the extent to which individuals engage differently with people of similar vaccination status significantly influenced disease dynamics and risk in people who opt to get vaccinated.

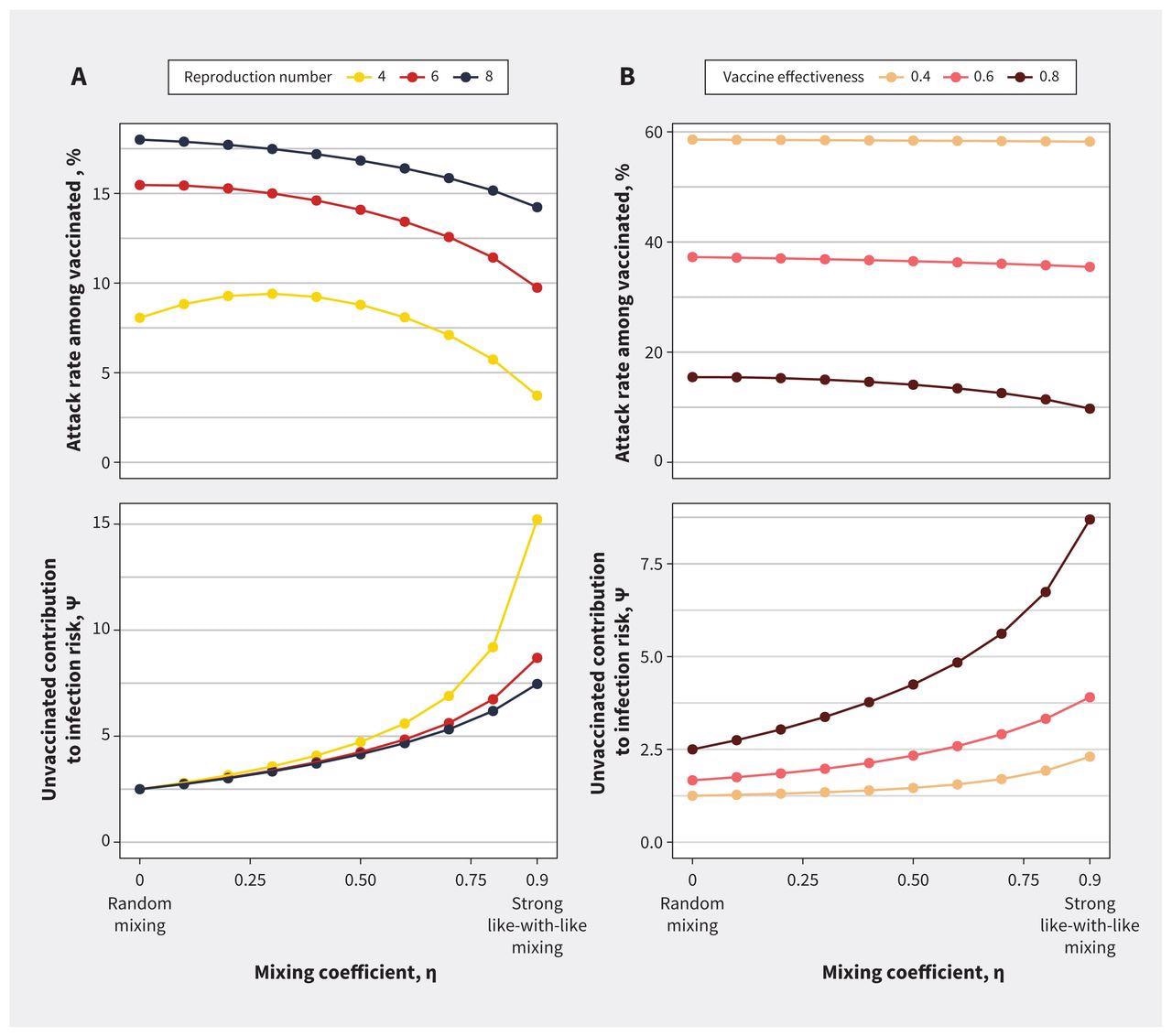

Impact of mixing between vaccinated and unvaccinated subpopulations on contribution to risk and final epidemic size for (A) varying reproduction numbers and (B) vaccine effectiveness. Both panels show the impact of increasing like-with-like mixing on outbreak size among the vaccinated subpopulation and contact-adjusted contribution to the risk of infection in vaccinated people by unvaccinated people (ψ). As like-with-like mixing (η) increases, the attack rate among vaccinated people decreases, but ψ increases. This relation is seen across a range of (A) initial reproduction numbers and (B) vaccine effectiveness. These effects are more pronounced at lower reproduction numbers and are attenuated as vaccines become less effective. We used a base case estimate of 6 for the reproduction number in the sensitivity analysis on vaccine effectiveness and a base case estimate for vaccine effectiveness of 0.8 in the sensitivity analysis for R.

Random mixing of vaccinated subjects with unvaccinated lowered the SARS-CoV-2 attack rates among the latter cohort by acting as a viral transmission buffer. Further, the probability of infection was significantly greater among unvaccinated individuals than among vaccinated ones under all mixing models. Unvaccinated participants exhibited a disproportionate contribution to infection risk following contact count adjustment. The authors observed unvaccinated people infected vaccinated subjects at a greater rate than the contact numbers alone-based predicted levels.

COVID-19 attack rates among vaccinated persons declined from 15% to 10% when like-with-like mixing expanded and elevated from 62 to 79% among unvaccinated people. Nevertheless, the contact-controlled contribution to risk within vaccinated people obtained from interaction with unvaccinated people rose. Since this excess contribution to risk could not be remedied by high like-with-like mixing undercuts the notion that vaccination was a personal choice and upholds robust public actions intended to increase vaccine uptake and limit access to public areas for unvaccinated people. The researchers also mentioned that regulatory and legal instruments to control practices and behaviors that put the public at risk stretch past communicable infectious illnesses, such as smoking bans in public places.

The researchers discovered that when vaccination efficiency was poor, like-with-like mixing was less protective in the setting of immune evasion exhibited with the recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. This discovery emphasizes the pandemic's dynamic character and the necessity for policy to adjust responsibly as the disease's nature and the protective effects of vaccinations change.

Conclusions

Collectively, the present work depicted that although the risk of not being vaccinated during a severe pandemic falls chiefly on the unvaccinated people, their decisions impact the chance of viral infection among the vaccinated in a way that was disproportionate to the number of unvaccinated individuals in the community. The authors mentioned that unvaccinated persons face a risk that cannot be deemed self-regarding.

Further, the concerns about equality and justice for individuals who choose to be vaccinated and those who choose not to be vaccinated must be factored into vaccination policy design. Given the wide range of sensitivity analyses, the current findings can be employed in future assessments when new SARS-CoV-2 variants arise, and novel vaccine preparations become available, as it illustrates the length of time vaccination imparts protection.