In a recent study published in The American Journal of Medicine, researchers assessed 3D printed masks as an alternative to N95 respirators.

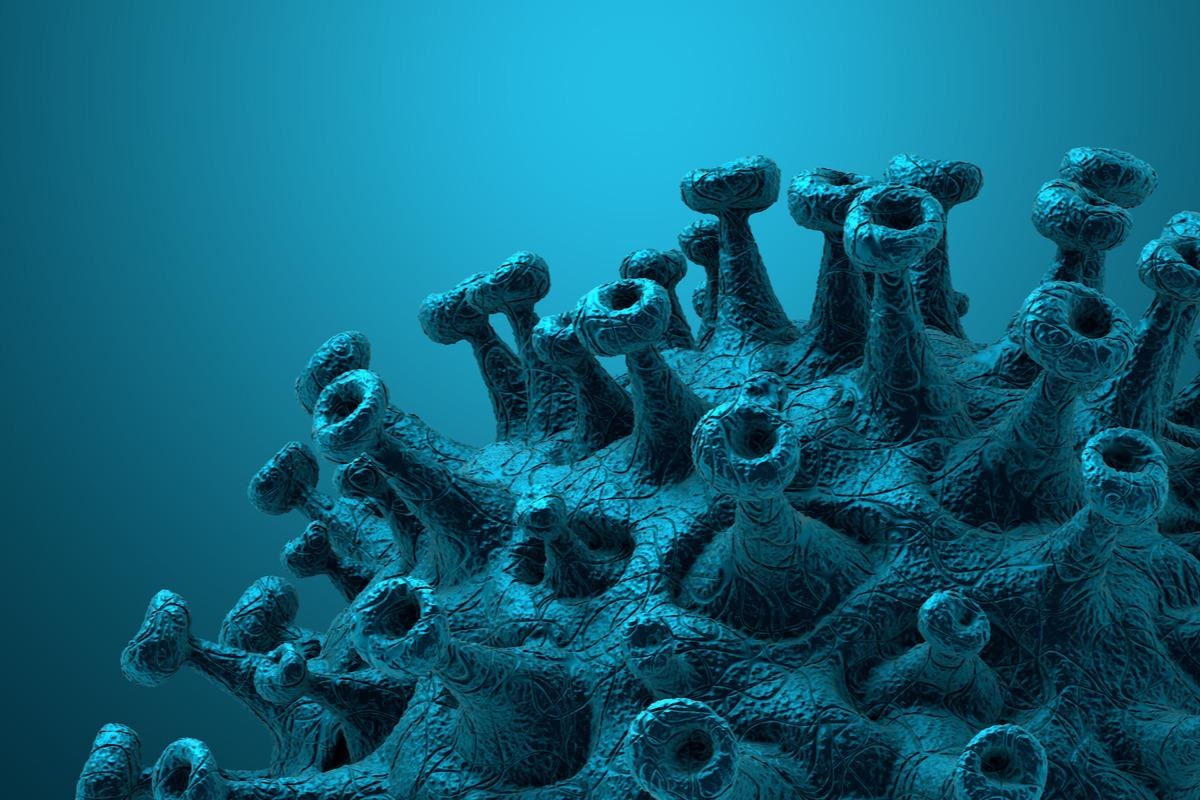

Study: Face Off: 3D Printed Masks as a Cost-Effective and Reusable Alternative to N95 Respirators: A Feasibility Study. Image Credit: CROCOTHERY/Shutterstock

Study: Face Off: 3D Printed Masks as a Cost-Effective and Reusable Alternative to N95 Respirators: A Feasibility Study. Image Credit: CROCOTHERY/Shutterstock

N95 masks have been proven to provide significant protection against the transmission of respiratory diseases like coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, supply shortages have highlighted the urgent need for an effective and safe alternative to the N95 mask.

About the study

In the present study, researchers tested three popular 3D printed masks based on their fit on a diversity of face shapes, as compared to the KN95 and the N95 masks.

The team searched repositories of 3D printing designs such as Thingiverse and MyMiniFactory for terms including ‘respirator’ and ‘covid’ and found three masks eligible for the study. The designs were subsequently imported and sliced as per recommended settings. The study participants were selected from undergraduate pre-medical and medical students belonging to the same institution. None of the five respondents had any contraindications, such as any chronic pulmonary disease. The participants were eligible for the study if they were aged 18 and above and if they were able to provide informed consent and wear and remove masks independently.

The researchers took the facial measurements of the participants. The facial length was evaluated from the bridge of the nose to the chin, while the width of the face was calculated from the nose tip to the top of either ear. The participants were clean-shaven on the day of testing.

The team also performed fit testing by employing a particle counter and a particle generator. The fit test comprised four trials that simulated daily activities or movements taking into account the testing conditions recommended by the OSHA protocols such as: (1) 50 seconds of leaning forward; (2) 30 seconds of speaking; (3) 30 seconds of moving one’s head from side to side; and (4) 30 seconds of moving one’s head up and down. The fit factor (ffx) for each trial x was evaluated automatically by calculating the area under the curve that represented the particles determined inside the respirator. The team performed the fit test in order to compare the efficacy of KN95 masks to that of N95 masks.

The team also fit each 3D printed mask to every participant using heat molding by heating the mask with a hair dryer until the plastic was malleable. The participants then pressed the heated mask against their faces by applying slight pressure with their index fingers and thumbs. The volunteers were instructed to focus on the nose while molding to properly gauge the fit of the mask. The team then secured an N95 with a hose attachment to the filter portion of the 3d printed mask to perform a fit test.

Results

The study results showed that only the low poly COVID-19 face mask passed the OSHA N95 fit test for all the eligible volunteers. In two of the participants, the standard 1860S N95 mask failed the fit test, due to which the 46727 model N95 was then used. When one of the participants was tested again, the fit factor for the low poly COVID-19 face mask remained unchanged even after it was printed in thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) as opposed to polylactic acid (PLA).

The team also found no difference in the fit factor when the filter for the low poly COVID-19 face mask was changed to a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter with 95% filtration or a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)-approved N95 replacement filter. Notably, changing the filter to KN95 resulted in an insufficient fit factor that was similar to that of a surgical mask.

Conclusion

Overall, the study findings showed that the low poly COVID-19 face mask provided an inexpensive, easily manufacturable, reusable, and customizable respirator that was comparable to the N95 masks in terms of protecting against COVID-19 and similar respiratory pathogens. The researchers believe that the present study lays the foundation for the development of more efficient face masks in the future that (1) enable efficient filtration; (2) fit better on a diversity of faces; (3) reduce the utilization of factors including time, resources, and material used in the production of masks; and (4) improve the recognition and production of mask designs that provide adequate protection against respiratory pathogens.