Mild upper respiratory illness is known to be caused by the four common human coronaviruses (HCoVs), which include 2 beta (HCoV-HKU1 and HCoV-OC43) and 2 alpha (HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E) coronaviruses. These HCoVs, unlike betacoronaviruses (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus), have been observed to be endemic among humans, as indicated by their continuous and widespread transmission.

The circulation of HCoVs takes place in a seasonal pattern in the US that peaks from December to March, with the predominant types differing yearly. However, the seasonality parameters have not been defined yet. Moreover, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an alteration in the national pattern of respiratory viruses during the 2020-2021 season.

A new study published in the Emerging Infectious Diseases journal aimed to analyze the circulation of four common HCoVs from July 2014 to November 2021 in the US.

Synopsis: Seasonality of Common Human Coronaviruses, United States, 2014–2021. Image Credit: Inside Creative House / Shutterstock

Synopsis: Seasonality of Common Human Coronaviruses, United States, 2014–2021. Image Credit: Inside Creative House / Shutterstock

About the study

The study involved collecting data from the National Respiratory and Enteric Viruses Surveillance System (NREVSS), established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to analyze the circulation of HCoVs. In addition, data on the number of tests performed and detection of HCoVs were collected from commercial, public health, and clinical laboratories, followed by their submission to NREVSS.

Specimen-level data were also collected through the Public Health Laboratory Interoperability Project (PHLIP), which also carried out the analysis of the age and sex of patients as well as the codetection of HCoVs with other respiratory viruses. The data was compiled based on total HCoV testing, positive detections, US census region, and season. Finally, the onset and offset of seasons were evaluated between the morbidity and mortality weekly report (MMWR week 31) and MMWR week 30 of the following year.

Study findings

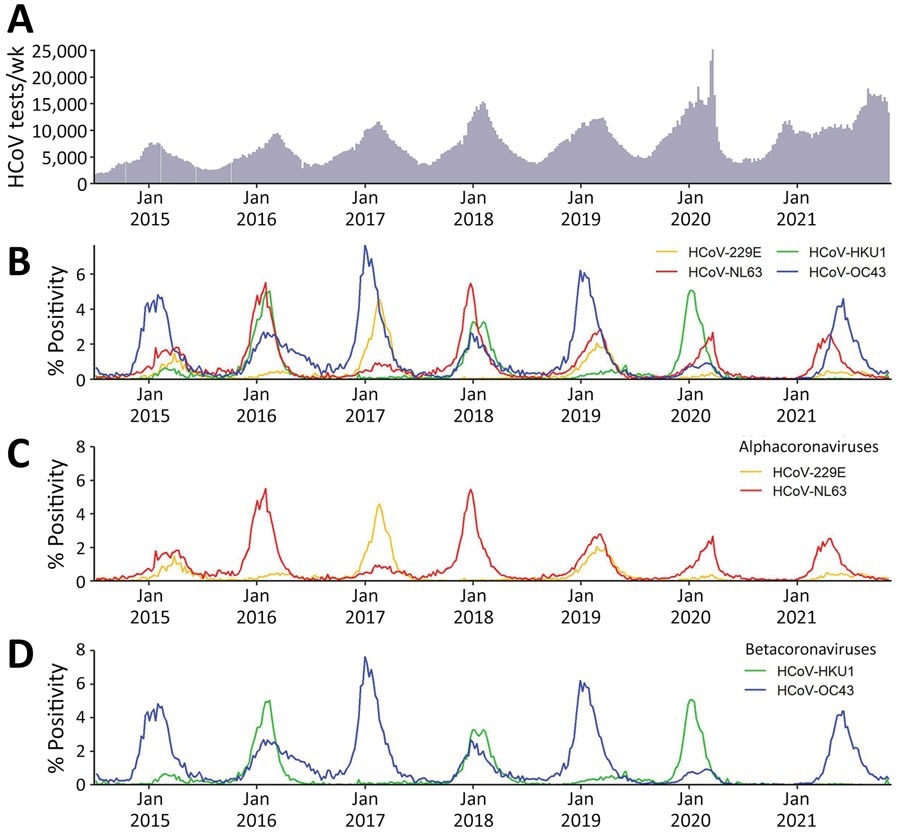

The results indicated the detection of HCoV of any type in 104,911 specimens out of the total 2,878,479 specimens that were submitted during the study period. Among them, 40% were reported to be positive for HCoV-OC43, 12.2% for HCoV-229E, 19.9% for HCoV-HKU1, and 27.8% for HCoV-NL63. Moreover, the weekly testing volumes were observed to be higher during the onset of the pandemic in March 2020.

Before the pandemic, the seasonal onsets were observed to be during October–November, offsets during April-June, and peaks during January-February. Most of the HCoV occurrences were found to take place between onset and offset. For 2020-2021, the onset was observed to be delayed by 11 weeks as compared to the previous seasons. Further, the number of days between peak and onset was longer in 2020-2021, and normal values for offset could not be reached.

Furthermore, the predominant type of alpha HCoV for most of the seasons was reported to be HCoV-NL63, while the predominant type of beta HCoV was HCoV-OC43, which, however, alternated with HCoV-HKU1 in a biennial pattern. Additionally, the detection of HCoV was found to be similar among males and females in the PHLIP subset. Among the four types of HCoV detected from PHLIP, HCoV-OC43 was most often observed among children aged below one year and adults aged between 66 to 100 years, while HCoV-229E was observed among those with the highest mean age. Finally, the codetection of the influenza virus with HCoV was found to be most common among other respiratory viruses.

Therefore, the current study demonstrates that the circulation of HCoVs generally begins during October–November, followed by their peak in January, and ends during April-June in the US. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-2021, HCoV circulation patterns were altered. To better manage patients and prepare for outbreaks, clinicians and public health communities should be aware of seasonal variations in HCoV circulation.

Total tests and percentage positivity of 4 common HCoVs from weekly aggregated data submitted to the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System, United States, July 2014–November 2021. A) Total specimens tested for all 4 HCoV types. B) Percentage positivity of the 4 HCoV types by week. C) Percentage positivity of the common alphacoronaviruses. D) Percentage positivity of the common betacoronaviruses. HCoVs, human coronaviruses.

Limitations

The study has certain limitations. First, the change in testing patterns due to the focus on SARS-CoV-2 testing during 2020-2021 could impact its comparison with the previous seasons. Second, the true burden of illness could not be analyzed. Third, the results might not be locally or nationally representative. Fourth, the specimen level data and type of laboratory participation for PHLIP might not be comparable with NREVSS.