Although a high intake of whole grain foods reduces the risk of cardiometabolic diseases, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancers, the underlying mechanism behind this occurrence is unclear. Whole grain foods tend to be healthier due to their high dietary fiber and phytoconstituents, typically lost during refining.

Quinoa belongs to the Polygonaceae family and has been categorized as a whole grain. Compared to other cereals, it has a high protein content, soluble and insoluble fibers, and carbohydrates that take longer to digest. Additionally, quinoa contains a high concentration of conjugated, free, and bound (poly)phenolics, such as saponins.

Quinoa's ability to pass through the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and eventually reach the lower GIT, home to the gut microbiome, is one of its essential properties. Upon reaching the lower GIT, quinoa undergoes fermentation by the gut microbiome and, subsequently, produces products such as bound (poly) phenolics, short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and other phytochemicals. The host utilizes these products during their metabolic functions.

In the last decade, due to advancements in technological, molecular, and computational methods, the gut microbiome has attracted much attention. Previous studies using the aforementioned advancements have revealed the existence of a complex symbiotic relationship between gut microbes and hosts. The gut microbiome assists in the host's digestion, absorption, and fermentation of dietary fiber and other food components. Hence, the digestion process depends on the composition of the gut microbiome.

About the Study

Pre-clinical studies have shown that quinoa consumption can modulate the gut microbiome and reduce blood glucose when ingested in a wheat flour bread matrix. A recent Nutrients journal study assessed the gut microbiome changes after consuming quinoa-enriched bread in a randomized cross-over trial.

The current cross-over trial included two treatment periods consisting of four weeks, separated by a four weeks washout period. All the participants were above 35 years of age, non-smokers, and were not under any medication.

As a part of the experimental design, the treatment group participants were given one quinoa-enriched bread roll per day, whereas the control group, or those subjected to placebo treatment, received a bread roll containing no quinoa. In addition, although participants were recommended typical diets, they were asked not to consume any whole-grain foods during the study period.

Blood and stool samples were collected during the study period, i.e., at the beginning of each 4-week treatment period. DNA was extracted from stool samples and subjected to 16S rRNA sequencing.

Study Findings

A total of 37 male participants enrolled in this study, among which nine dropped out during the study period. The mean age of the participants was 51.5 years, and the average body mass index (BMI) was 27.7 kg/m2.

The BMI, blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose of all participants remained unchanged during the study period. The quinoa bread and control bread contained 6.52 g/100 g and 3.60 g/100 g of dietary fiber, respectively.

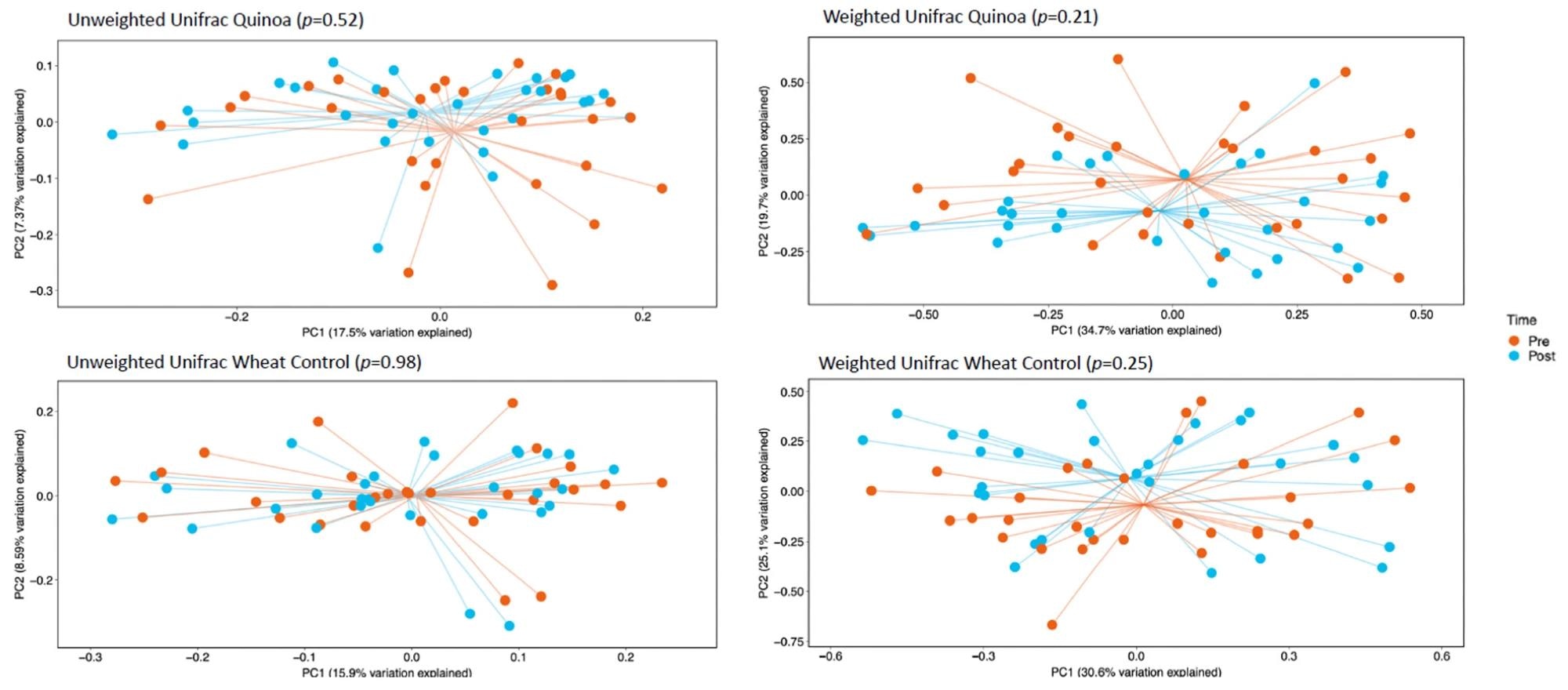

Principle coordinate analysis (PcoA) of unweighted UniFrac analysis and weighted UniFrac analysis pre- (baseline) and post-consumption (post) for quinoa and control wheat bread pre-baseline and week 4.

Principle coordinate analysis (PcoA) of unweighted UniFrac analysis and weighted UniFrac analysis pre- (baseline) and post-consumption (post) for quinoa and control wheat bread pre-baseline and week 4.

The stool samples were compared to assess the impact of the quinoa and the control wheat bread on the gut microbiome. Interestingly, the gut microbiome profiles developed in the current study indicated a similar composition to any adult human stool sample. Two of the dominant bacterial phyla present in the stool samples were bacteroidetes and firmicutes.

The control and treatment groups observed a non-significant increase of firmicutes, by around 7.5% and 4.4%, respectively. Similarly, a non-significant reduction in the bacteroidetes level was observed between the two groups. An increase in Fusicatenibacter (1.4%) and Subdoligranulum (1.9%) was found in the control group. In contrast, changes in genera Anaerostipes and Dorea were observed in the quinoa bread-consuming group. However, none of these changes were statistically significant.

Both the control and treatment groups revealed no significant changes in α-diversity between baseline and week 4. This study estimated α-diversity by comparing the number of observational taxonomic units (OTU) before and after the treatment periods.

The findings of this study contradicted a previous pre-clinical animal model-based study that indicated statistically significant changes in bacterial composition due to quinoa consumption. Nevertheless, the findings were in line with another previous study where patients with increased dietary fiber intake via the consumption of different types of whole grains showed no changes in microbial diversity metrics.

Conclusions

The current study revealed that four weeks of consuming quinoa-enriched bread did not alter specific bacteria phyla and genera composition or the α-diversity of the gut microbiome. In the future, more research is required to understand better whether a specific dosage of quinoa could alter the gut microbiome and if these alterations bring about physiological health benefits.