The study aimed to investigate the intestinal microbiota composition changes associated with these diets for a period of 12 weeks.

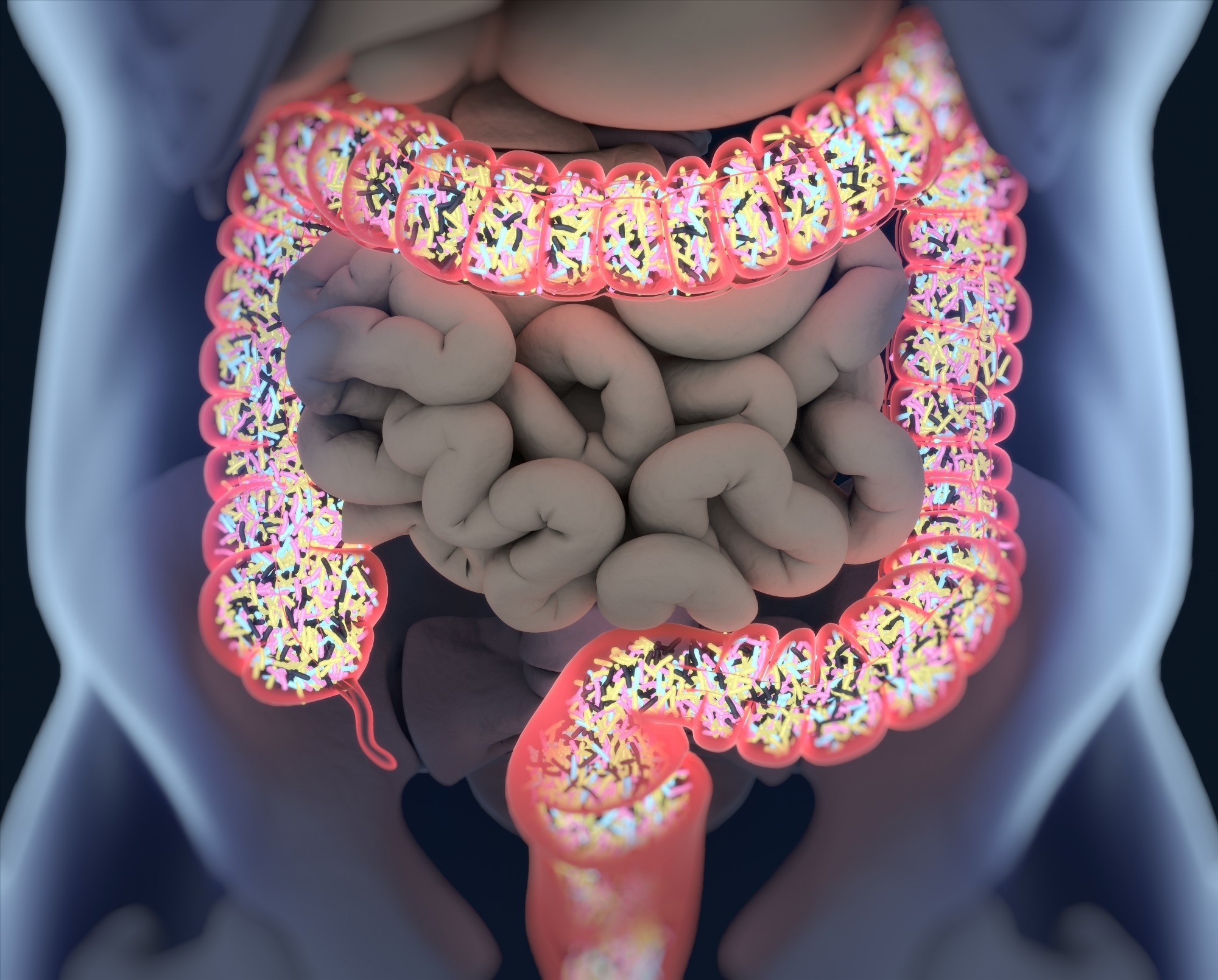

Study: The Effect of a Planetary Health Diet on the Human Gut Microbiome: A Descriptive Analysis. Image Credit: AnatomyImage/Shutterstock.com

Study: The Effect of a Planetary Health Diet on the Human Gut Microbiome: A Descriptive Analysis. Image Credit: AnatomyImage/Shutterstock.com

Background

The EAT-Lancet Commission, a conglomerate of 37 leading scientists from 16 countries, developed the PH diet in 2019.

So far, studies have not evaluated the effect of a PH diet on the human intestinal microbiome, which is a key determinant of human health.

About the study

In the present study, researchers divided participants into three groups, two control groups, who followed either a VV or OV diet for a minimum of one year and the intervention group following the PH diet.

The PH diet followers began using recipes and instructions per the EAT-Lancet commission guidelines as they switched from an OV to a PH diet. They tracked any divergence from the recommended foods throughout the study.

The team enquired from all participants about what they ate two days before fecal collection and about their alcohol intake at any time during the study duration to reduce any potential bias arising because of the consumption of different foods shortly before sample collection.

They collected fecal sample(s) at four different time points: the beginning of the study and after two, four, and 12 weeks. They extracted deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from these samples to perform whole metagenome sequencing.

Additionally, they used matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) to analyze bacteria extracted from these samples and cultivated on agar plates.

Results

The study population comprised 41 healthy adults aged ≥18 years who agreed to voluntarily participate in this study in the Saarland area of southwest Germany between January and April 2022.

Of 41 participants between 16, nine, and 16 adhered to an OV, VV, and PH diet, respectively. Notably, the VV group had more females (8/9), though sex ratios varied significantly across all three groups.

The researchers noted a relatively stable α-diversity for all diet groups during the 12-week study period, although they observed slight changes among some participants at different time points.

The relative abundance of Bifidobacterium adolescentis increased from 3.79% to 4.9% after 12 weeks in the PH group. Notably, its abundance increased the most in the VV group.

Differential abundance analysis of the PH group also highlighted a minimal spike in some probiotic species, such as Paraprevotella xylaniphila and Bacteroides clarus.

Taxonomic profiling enabled the visualization of α-diversity-related differences across all three study groups. At the genus level, the researchers noted that VV group people, immediately after inclusion, had two to three times the relative amount of Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, and Gemmiger species in their intestine compared to OV and PH group controls. The relative abundance of Prevotella species was 1.3% in the OV group.

Though not considered significant during differential abundance analysis, within four weeks of following the PH diet, Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Coprococcus eutactus bacterial species increased in abundance in the gut by two-fold.

A previous study showed that consuming inulin, a type of dietary fiber, increases the abundance of B. adolescentis in the gut. This bacterium degrades inulin into lactate and acetate, which is then used by short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-synthesizing bacteria, e.g., Enterococcus rectale, to produce the SCFA butyrate.

Focusing on the top 10% effect sizes helped the researchers analyze the differential abundance of some potentially interesting species between OV and VV groups.

For instance, among the PH group individuals they observed three-, four-, and 18-fold surge in Prevotella copri, Paraprevotella xylaniphila, and Bacteroides clarus species, respectively.

Conversely, the PH group showed a six-fold decreased abundance of Firmicutes bacterium CAG 94, suggesting that the PH diet shifted parts of the microbiome composition towards a VV microbiome. This bacterium is another interesting target for future research aimed at the development of novel probiotics that could supplement a healthy diet.

The PH group participants mainly contained these four species, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Bacteroides uniformis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Streptococcus salivarius.

Conclusions

According to the present study findings, complemented with metagenomics-sequencing-based appraisal, the PH diet did not change the overall intestinal microbial composition but favored the growth of many beneficial bacterial species.

Switching to the PH diet favored the growth of bacterial species, such as B. adolescentis and P. copri. SCFA-producing bacteria exert many beneficial anti-inflammatory and regulatory effects on the host.

However, they might inhibit the growth of other beneficial microbiota or increase the risk of some diseases. e.g., a recent found that P. copri abundance favored the development of rheumatoid arthritis, although the evidence was inadequate.

Thus, cross-country, longitudinal, large-scale studies should extensively analyze the effect of PH diet on health, homeostasis, and gut functionality.

Furthermore, additional research is warranted to confirm the current study findings that the PH diet slightly increased probiotic bacteria in the gut at ≥four weeks.