The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has had a significant impact on the global economy and healthcare sector.

Several studies have indicated that one out of ten patients experiences persistent symptoms for a prolonged period, a condition that has been referred to as ‘long COVID’ or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Common long COVID symptoms include breathlessness, gastrointestinal (GI) disturbance, fatigue, and memory impairment. To date, the association between disease phenotypes and mechanisms has not been clearly understood.

A recent study posted to the medRxiv* preprint server discusses the phenotypes associated with long COVID inflammation.

Study: Large scale phenotyping of long COVID inflammation reveals mechanistic subtypes of disease.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Background

Due to the continual emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, the prevalence of long COVID has increased and will likely have long-term health effects. Thus, there is an urgent need for targeted management of long COVID, depending on specific phenotypes and underlying mechanisms.

Although some studies have revealed the manifestation of persistent inflammation in adults with long COVID, these findings have been limited by the timing of samples, breadth of the considered immune mediators, and sample size. These limitations have led to an inconsistent association with symptoms.

Nevertheless, one recent PHOSP-COVID study revealed that the plasma proteome exhibited inflammation for those who experienced very severe long COVID symptoms, including fatigue, cognitive impairment, and breathlessness. However, it remains unclear whether proteomic changes are specific to symptoms.

It is essential to determine the common pathways of inflammation associated with long COVID symptoms. Likewise, it is important to understand whether different patterns of inflammation cause specific clinical subtypes that may require personalized therapeutic intervention.

About the study

The current prospective multicentred study included individuals, both male and female, above 18 years of age, without comorbidities, who were hospitalized for COVID-19 between February 2020 and January 2021. Plasma samples and relevant clinical data were collected approximately six months after hospitalization.

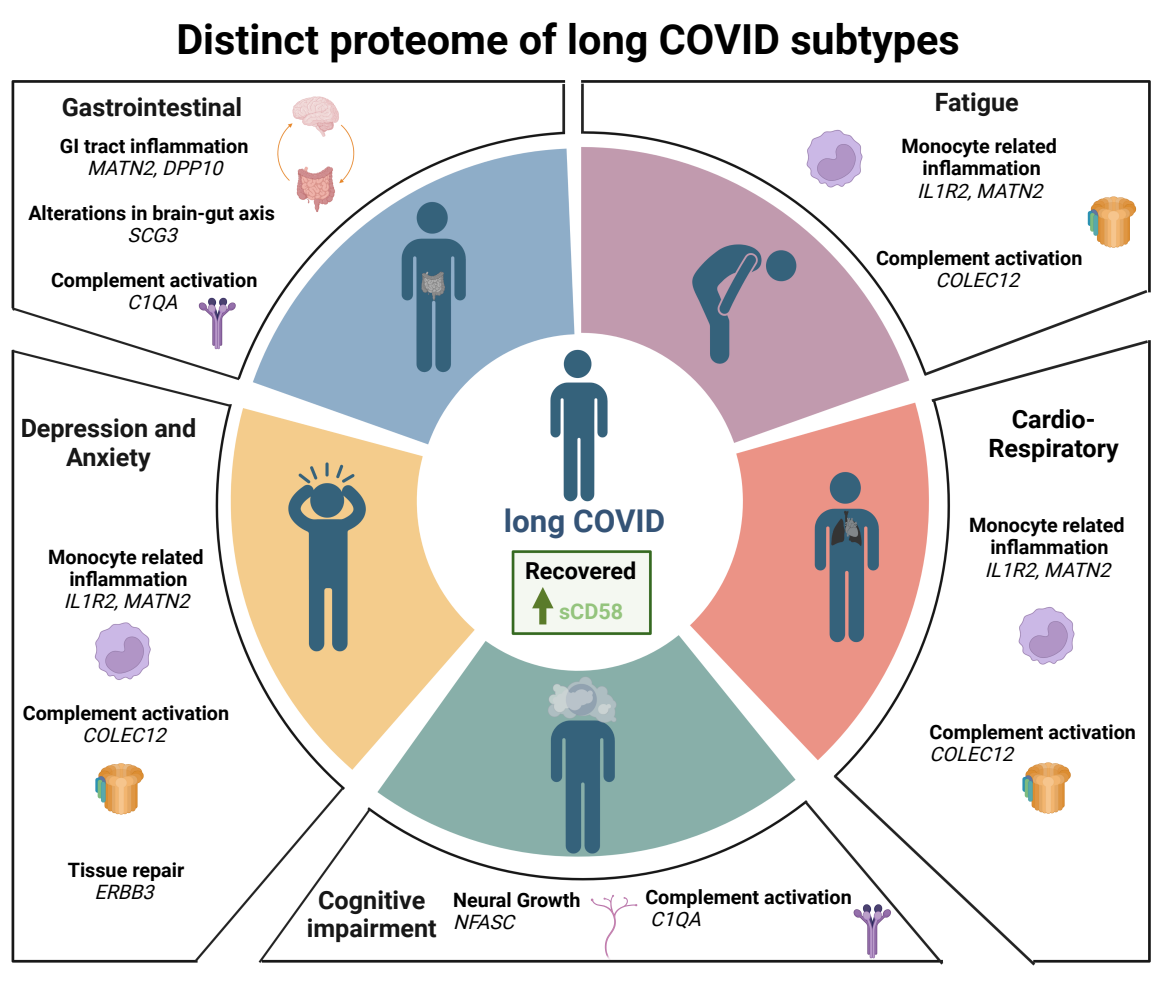

Based on clinical data, the patients were placed into six categories, of which included ‘Recovered,’ ‘Fatigue,’ ‘Cardiorespiratory,’ ‘GI,’ ‘Cognitive impairment,’ and ‘Depression/anxiety.’

Different scoring systems, such as the dyspnoea-12 score, Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness score, patient health questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) score were used to assess disease severity. Inflammatory signatures were determined using different assays.

Study findings

A total of 360 plasma proteins were measured in 719 participants six months after hospitalization due to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Herein, 35% of the cohort was categorized under ‘Recovered’, and the remaining 65% experienced long COVID symptoms.

A penalized logistic regression (PLR) model was used to assess the impact of patient’s demographics and immune mediators on symptoms. To this end, the female sex predicted all symptoms, particularly GI and cardiorespiratory symptoms.

Pre-existing conditions were identified to be a strong risk factor for all symptoms except GI. Notably, age and disease severity were not linked with any symptoms.

To assess the link between peripheral inflammation and long COVID symptoms, immune mediators were measured in the plasma. The PLR model adjusted coefficients and determined specific predictive mediators for each symptom group. Interestingly, mediators suggestive of persistent monocytic inflammation were correlated with all symptoms.

Elevated interleukin 1R2 (IL1R2) and/or Matrilin-2 (MATN2) were consistently associated with all symptoms except cognitive impairment. IL1R2 is expressed in macrophages and monocytes and influences IL1-driven inflammation. MATN2 is an extracellular matrix (ECM) protein that causes inflammation by triggering toll-like receptors and increasing the rate of monocyte infiltration into tissues.

IL-6 enhanced the risk of fatigue and cardiorespiratory symptoms. Colony stimulating factor 3 (CSF3) marginally influenced GI symptoms, fatigue, and anxiety/depression.

Increased levels of sCD58, an immunosuppressive factor, were linked with a lowering of all long COVID symptoms, particularly cardiorespiratory symptoms, and fatigue. Collectin-12 (COLEC12) was associated with an increased risk of developing anxiety/depression, fatigue, and cardiorespiratory symptoms. COLEC12 initiates inflammation by triggering the alternative complement pathway and modifying leucocyte recruitment.

C1QA, a component of the complement system, was identified as a predictor of long COVID symptoms, particularly cognitive impairment. Likewise, elevated levels of Neurofascin, Spondin-1, and Iduronate sulfatase also correlated with cognitive impairment.

Secretogranin 3 (SCG3), MATN2, and dipeptidyl peptidase 10 (DDP10) were associated with the highest risk of GI symptoms. Comparatively, delta/notch-like EGF repeat (DNER) was linked with a reduced risk of cardiorespiratory symptoms.

The findings of this study indicate that immunosuppressive factors and a robust tissue repair response might prevent cardiorespiratory symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

There was no significant difference in nasal mediator levels between those who recovered and those who developed long COVID. For individuals with cardiorespiratory symptoms, elevated levels of inflammatory mediators were detected in the plasma but not the upper respiratory tract.

Conclusions

Systemic monocytic inflammation and complement activation appear to be the underlying mechanisms associated with long COVID. Therefore, the resolution of these factors should assist in recovery.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.