Loneliness is the distressing feeling that occurs when there is a discrepancy between one's desired and actual level of social connection. It is often characterized by the perceived inability to form meaningful relationships. Loneliness expresses itself through a spectrum of social impairments that cause and sustain loneliness through multiple contributory pathways.

This experience requires studying multiple disciplines, including neuroscience, sociology, and clinical medicine. A recent review in the journal Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews presents a multidimensional model of loneliness.

Study: A translational neuroscience perspective on loneliness: Narrative review focusing on social interaction, illness and oxytocin. Image Credit: Eakachai Leesin / Shutterstock

Study: A translational neuroscience perspective on loneliness: Narrative review focusing on social interaction, illness and oxytocin. Image Credit: Eakachai Leesin / Shutterstock

What is loneliness?

The Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection describes it as "a subjective unpleasant or distressing feeling of a lack of connection to other people, along with a desire for more, or more satisfying, social relationships.'

Loneliness is, therefore, both subjective and distressing. It cannot be assessed entirely or predicted by objective parameters such as social isolation or a small social network. As the birth rate falls in the developed world, loneliness may be expected to rise in prevalence among an aging population.

This motivated the current study, which was conducted as a narrative review based on currently available peer-reviewed literature on loneliness from various perspectives. In both animal and human studies, these included social interactions, psychiatric illness, physical disease, touch, and oxytocin.

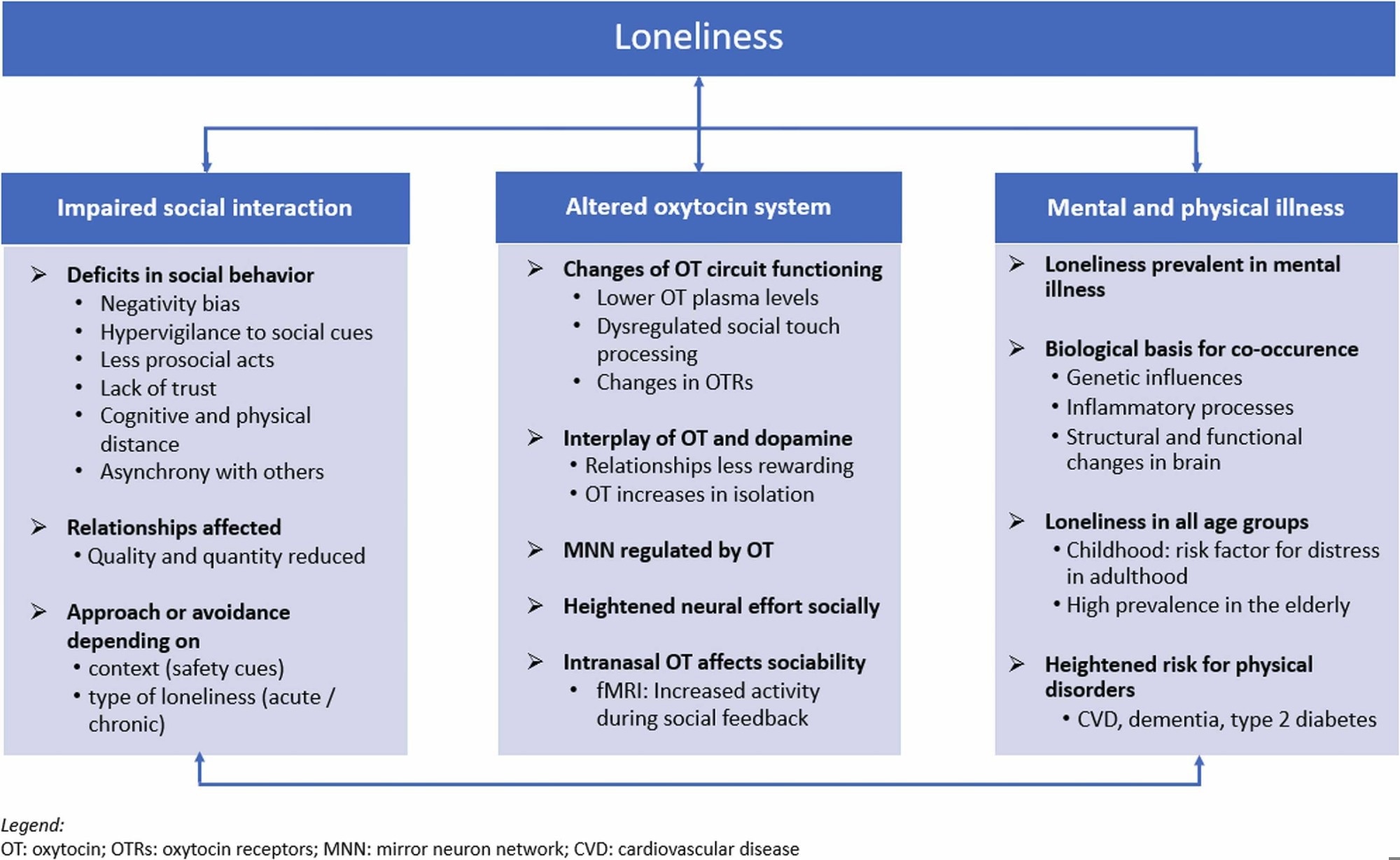

Translational model for loneliness summarizing central findings on social interaction, OT and illness.

Translational model for loneliness summarizing central findings on social interaction, OT and illness.

Loneliness affects social interactions

Lonely people find it challenging to have meaningful social interactions. They focus on the negatives of such interactions while experiencing lower satisfaction and more conflict.

They are more closed, hesitate to work synchronously, and are unlikely to seek social contact or emotional intimacy. Overall, this may be called hyposociality.

On the other hand, lonely people act up in public because they need to form relationships. They experience more good feelings with people close to them rather than strangers, similar to the brain's responses to food cues after a starvation period. Lonely people often seek comfort from sweet drinks or illegal substances. This could indicate their hypersociality.

Thus, loneliness may be a physiological response to lacking social connections.

Lonely people react to social situations differently, based on how long they have been lonely (acute or chronic) and whether the environment is safe or unsafe. Acceptance, security, and the need for minimal effort for social interaction can help such people to enhance their social activity.

Acute loneliness prompts lonely people to actively seek connections. In contrast, chronic loneliness realigns them towards avoidance and asynchrony with other people. These are defensive behaviors meant to prevent rejection and avoid social threats.

Loneliness and oxytocin

Oxytocin is the bonding hormone and promotes the seeking of social relationships and pairs. Oxytocin-secreting cell density and oxytocin levels increase with loneliness, suggesting a compensatory role for emotional deprivation caused by social isolation.

Isolation-related increases in oxytocin production are involved in increasing the relevance and processing of social stimuli. With chronic loneliness, oxytocin levels decline in an adaptive manner.

Oxytocin receptors are expressed in multiple regions of the brain, affecting social behavior in a region-specific manner. The oxytocin system's sensitivity also varies with social interaction.

The intranasal administration of oxytocin enhances brain reward area connectivity, familiarity, responsive emotional memory processing, and focus on positive facial cues. Thus, the oxytocin system physiology underlies but also responds to the characteristic changes in lonely individuals, such as a negative view of social interactions.

Social touch triggers oxytocin release, increasing the pleasantness of the experience and reducing its threat. This benefits relationships in mentally healthy people. Oxytocin neurons connect to sensory cortical regions as well as to the insula, indicating their importance in normal social touch processing.

Dysregulation of the oxytocin system contributes to a negative perception of social touch in lonely people when coupled with impaired integration of multiple sensory inputs in the insula. It affects multiple processes, like social seeking, pair bonding, trust, and emotional recognition, that are key to building relationships.

Individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and childhood abuse have widespread malfunction of these connections, causing hyper-reactivity and fear or aversive responses to social touch. They also react weakly to reward stimuli following positive social interactions. The outcome is avoidance, negative perceptions by others, and feelings of further disconnectedness.

This agrees with the observation that mental illness often sets in during late adolescence or early adulthood when loneliness is most frequent. Other than childhood stress, inflammation, genetic factors, gut dysbiosis, and even changes in the brain's structure and function have been linked to loneliness.

Loneliness and illness

Lonely people are at higher risk for both mental and physical illness. Loneliness is a marker of depression. Lonely people are at more risk for severe depression and anxiety, as well as for personality disorders, schizophrenia, alcoholism, and bulimia.

Mental illness can produce and exacerbate loneliness as well. The two may have common biological origins and mechanisms. With either physical or mental illness, patients enter a vicious cycle of isolation-loneliness-isolation that prevents their recovery.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is 30% more common with loneliness, which outranks even diabetes as a risk factor. Loneliness also increases mortality risk in cancer patients. Type 2 diabetes is bi-directionally related to loneliness.

Loneliness is also a risk factor for dementia. Caregivers of dementia patients are additionally affected by loneliness, presenting an important public health issue in modern society.

Loneliness predicts suicidal thoughts in some subgroups. It also reduces self-efficacy and may thus prevent the proper management of medical illnesses, even possibly causing early death as a result.

The converse is also true, with loneliness as the cause and consequence of issues arising in three interconnected domains: social awkwardness, malfunctioning of the oxytocin system, and illness (physical or psychiatric).

Conclusions

"Impaired social interaction, the OT system and illness are interconnected in lonely people and recognizing these links is central to understanding the complex construct of loneliness."

Future research should focus on identifying and exploring the interconnections and the conditions under which loneliness occurs as a cause or result. The role of oxytocin administration needs to be investigated, and other preventive aspects of addressing loneliness for mental health must be studied.