New research shows that cutting down on sitting time significantly reduces metabolic syndrome risk in older adults—even among those who don’t meet exercise guidelines or follow perfect diets.

Study: Associations between time spent in sedentary behaviors and metabolic syndrome risk in physically active and inactive European older adults.

A study published in The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging highlights the importance of being physically active and limiting sedentary behaviors in improving metabolic health among physically active or inactive older adults.

Background

Physical activity is a vital lifestyle factor that strongly influences cardiovascular health. The current global guidelines recommend more than 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week, together with limiting sedentary behaviors for older adults, to improve metabolic health and reduce metabolic syndrome risk.

Metabolic syndrome refers to a group of metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, which collectively increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, especially among older adults.

Older adults spend most of their time in sedentary pursuits. This sedentary lifestyle, combined with a reduced level of physical activity, increases their risk of developing cardiometabolic abnormalities.

Existing evidence links excessive time spent in sedentary behaviors to increased risk of morbidity and mortality. However, it remains uncertain whether sedentary behaviors independently contribute to metabolic risk or whether their negative impact can be attenuated by engaging in regular physical activity, as per the current guidelines.

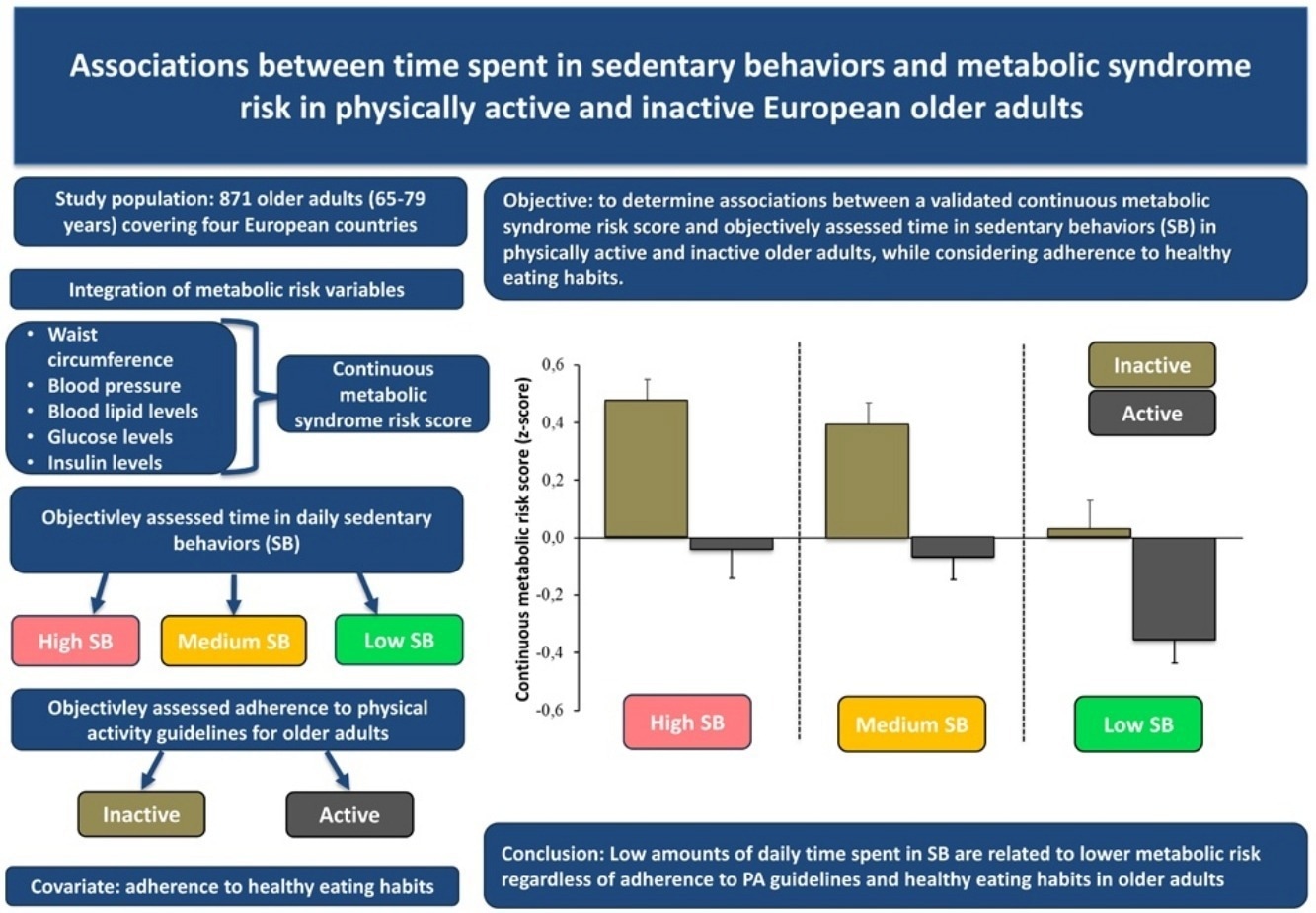

The current study aimed to gain deeper insights into the impact of sedentary behaviors on metabolic risk among physically active and inactive older adults, with a focus on a validated continuous metabolic syndrome risk score and considering their adherence to healthy eating behaviors.

Study design

The current study utilized baseline data from the NU-AGE study (the Northwestern University Aging Research Registry), which was a randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of a healthy diet on the biomarkers of inflammaging in older European adults.

This study specifically analyzed NU-AGE baseline data on physical activity behaviors and metabolic risk factors in 871 community-dwelling older adults (age range: 65–79 years) from four European countries.

Participants’ physical activity levels and time spent in sedentary behaviors were assessed for a week using accelerometers that they wore during waking hours. The percent of daily time spent in sedentary behaviors was categorized based on mathematically derived tertiles (one-third of the total data) of sedentary behaviors (low, medium, and high tertiles).

Five metabolic risk factors were analyzed and used to create a continuous metabolic syndrome risk score (cMSy). Furthermore, participants' healthy eating habits were assessed using food records.

Study findings

The study reported that, on average, participants spent 60%, 37%, and 3% of their waking hours in sedentary behaviors, light-intensity physical activities, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activities, respectively.

Participants with the least time spent in sedentary behaviors (low tertile) had twice the amount of time in moderate-to-vigorous physical activities compared to those with the highest time spent in sedentary behaviors (high tertile).

About 50% of the study population was classified as physically active, performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week. The majority of physically active participants were in the low sedentary behavior tertile.

Risk of metabolic syndrome

The study found a significantly lower risk of metabolic syndrome, measured using the continuous metabolic syndrome risk score, among physically active and inactive participants who spent a shorter duration of time in sedentary behaviors (low tertile) compared to those who spent medium and longer times in sedentary behaviors (medium tertile and high tertile), regardless of healthy eating habits.

In contrast, no significant difference in metabolic syndrome risk was observed between the medium and high sedentary behavior tertiles in either active or inactive participants. This finding suggests a potential threshold effect, where risk increases notably above 8.3 hours per day of sedentary time.

Further comparison between the active and inactive groups revealed that physically active participants have a significantly lower risk of metabolic syndrome across all sedentary behavior tertiles.

This finding indicates that 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week can significantly improve metabolic health in older adults, even if they spend longer periods in sedentary behaviors. Importantly, the beneficial effect of being physically active remained significant after adjusting for total MVPA time, suggesting that adherence to physical activity guidelines offers benefits even among highly active individuals.

Study significance

The study finds that the shorter the time spent in sedentary behaviors, the lower the risk of metabolic syndrome in older adults, regardless of their physical activity status and healthy eating habits.

Notably, the study highlights that the lowest risk of metabolic syndrome is associated with physical activity behavior characterized by shorter time spent in sedentary behavior combined with higher adherence to the current moderate-to-vigorous physical activity guidelines.

The study also finds that physically inactive participants who spend less time in sedentary behavior can achieve better metabolic health despite low levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Since less time in sedentary behavior mainly translates into more time in lighter-intensity physical activity, this finding suggests that light-intensity physical activity—even below moderate intensity—may offer meaningful metabolic health benefits. This is particularly encouraging for older adults who may find it challenging to meet moderate-to-vigorous physical activity targets.

The study also demonstrated that sedentary behavior has an independent association with metabolic risk—even when accounting for physical activity and diet—reinforcing the need to address sedentary time as a separate behavioral risk factor.

The study did not include older adults with frailty, dementia, or severe heart disease, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to healthier, community-dwelling older populations. Furthermore, because of the cross-section design, the study could not determine the causality of observed associations.