The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic spread rapidly around the world, leading to lockdowns, social distancing measures, and millions of deaths. However, with the help of mass vaccination campaigns and monoclonal antibody treatments, the transmission of the disease is beginning to slow down.

Vaccines rely on the immune systems ability to produce specific antibodies – most vaccines designed to effect severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) target the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit of the spike protein, as this is responsible for viral cell entry through binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). However, some viruses (including SARS-CoV-2) have an alternative method of infection known as an antibody-dependent enhancement of infection (ADE). It is one of the most significant risks for both vaccines and monoclonal antibody treatment and is of special concern given the rise of variants of concern such as the Delta variant – which is known to evade vaccine-induced immunity.

A group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been investigating the mechanisms and impact of ADE in SARS-CoV-2. A preprint of the groups' findings can be found in the journal mBio published by the American Society For Microbiology.

In ADE an immune complex of virus and non-neutralizing or cross-reactive antibodies binds to receptor molecules called Fcy receptors (FcyRs) on macrophages and monocytes. These cells then internalize the complex, allowing the virus to enter the cell.

Both SARS-CoV-1 ad MERS-CoV showed the ability to enter cells through ADE, and several studies have confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 has the same ability using FcyRIIA. Still, it is unknown whether FcyRIA or FcyRIIIA are also involved.

The researchers generated baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells expressing the three FcyRs or ACE2. Wild-type BHK cells are not susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, and as such, they make an ideal model to test whether the transfected proteins mediate ADE. BHK cells were infected with a luciferase-expressing vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike (VSV-SARS2-S). Luciferase activity was evaluated 24 hours post-transfection. Only the BHK cells that were expressing ACE2 proved susceptible to VSV-SARSS2-S transfection. Following this, the scientists used 15 convalescent-phase plasma samples randomly selected from a total of 110 samples, and one sample from an uninfected individual. The transfected FcyR BHK cells were then infected with VSV-SARSS2-S that had been incubated with these samples. No luciferase signals were detected at all, suggesting none of the FcyRs mediate ADE in BHK cells.

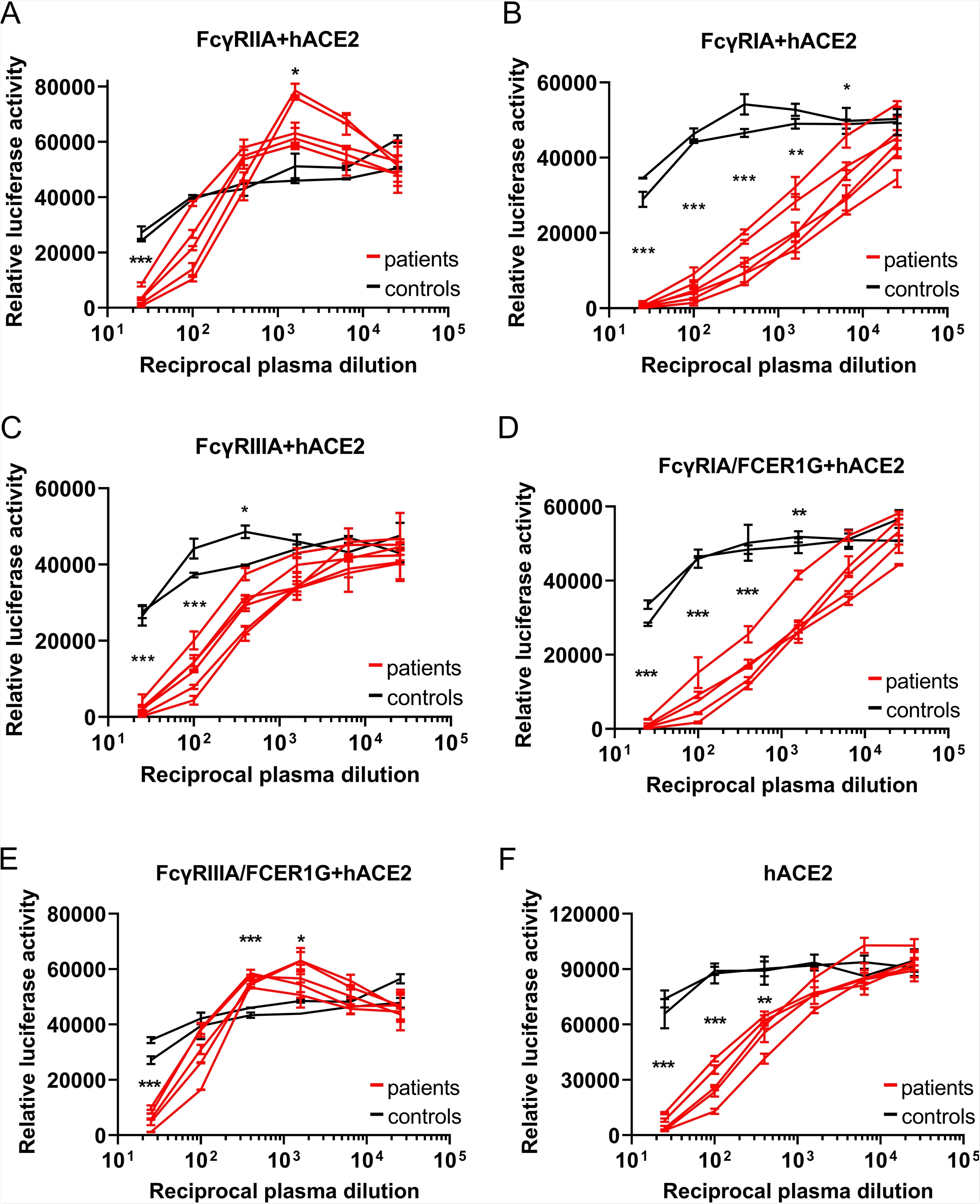

ADE of SARS-CoV-2 infection is mainly mediated by FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA. (A to E) Serially diluted convalescent-phase plasma from five individuals and two control plasma samples incubated with VSV-SARS2-S were used to infect the indicated cells that had been transfected with an hACE2 expression vector; the luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined at 24 hpi. The experiment was performed with duplicate samples; means and standard deviations (SD) are shown. (F) Serially diluted convalescent-phase plasma from two individuals and two control plasma samples incubated with VSV-SARS2-S were used to infect the indicated cells, and the luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined at 24 hpi. The experiments were performed in duplicate; means and SD are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

However, in FcyR BHK cells transfected with ACE2, luciferase levels were significantly higher when infected with VSV-SARS2-S incubated with increasingly diluted plasma, indicating that the FcyR enhanced VSV-SARS2-S infection. Fortunately, this was only seen with FcyRIIA, and not the other two receptors. To further investigate the possibility of ADE in SARS-CoV-2 infection, the researchers explored the possibility that an association with the FcRy subunit was required for the function of FcyRIA and FcyRIIIA. They engineered the BHK cells expressing those receptors once again, this time in order to allow them to express FCERIG (the subunit involved) stably. There was a significant increase in luciferase signals for FcyRIIIA-FCER1G BHK cells – suggesting that the FCERIG was necessary for activation. As no ADE of infection was detected in hACE2-BHK cells, these data suggest that ADE can aid SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Upon expanding the testing to include convalescent-phase plasma obtained 1, 3, and 6 months post-diagnosis – all showed positive results. These tests were repeated with primary human macrophages, but no SARS-CoV-2 replication was found.

The researchers propose that their results prove that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces antibodies that can cause ADE-induced infection, and that these antibodies persist for six months post-infection at a minimum.

The authors highlight the importance of their study given the emergence of multiple variants of concern, especially as the risk of reinfection could trigger a worse prognosis. This is because the variants antigenicity is different from the original strain found in Wuhan, China.

So while an infected individual will still have a robust immune reaction, it will be less effective against the new strain – while also paving the way for ADE-induced infection. The authors' findings are backed up by several studies, including similar results for SARS-CoV-2 replication in macrophages and a finding of a correlation between ADE-inducing antibodies and COVID-19 severity. These results could not only help inform treatment and drug development for this pandemic and future coronavirus diseases but could also be beneficial to governments attempting to devise public health policy. Unfortunately, the worrisome variants of concern appear even more dangerous with this new information.