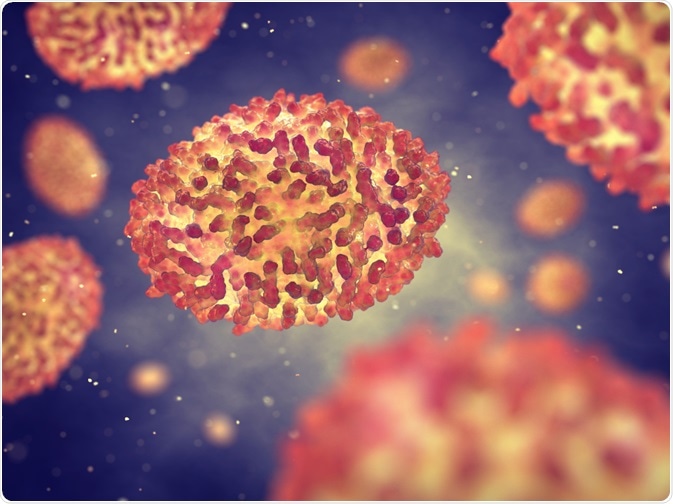

The variola virus belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus, the members of which cause skin lesions in mammals. Infection with this virus can cause several different patterns of illness, ranging from the “classic” vesiculopustular exanthema to a rapidly lethal disease lacking the typical rash, indicating that these clinical variants are typically determined by host factors.

Image Credit: nobeastsofierce / Shutterstock.com

One of the most intriguing questions in the evolution of the orthopoxviruses is the origin of the variola virus, which is estimated to have killed as many as 300 million people over the past several centuries. Genomic studies of a set of variola virus isolates have shown the patterns of phylogenetic relationships between geographic variants of this highly pathogenic virus.

The evolution of the virus

Unlike vertebrates, for which we have paleontological data, and RNA viruses, which exhibit a high rate of genetic variation, an objective estimate of time parameters for the molecular evolution of DNA viruses is a rather complex problem. This is primarily due to their low rate of accumulation of mutations.

As the variola virus lacks a known non-human animal reservoir, its origin as a human pathogen has been concealed under a veil of mystery. The evolutionary history of this virus can be dated based on either the assumed dates of variola virus subtypes diverging from the ancestors or the dates of isolated samples that contain the variola virus.

It is known that smallpox was exported to Central and South America from West Africa in the early 16th century, which resulted in epidemics with a high case fatality ratio among the local population. Important recombination events that play a role in the evolution of the variola virus created relatively short, local inconsistencies in phylogenetic trees.

Still, subsequent smallpox outbreaks in America had shown low lethality, and the virus that caused these epidemics was given the name variola minor alastrim. During its spread to the American continent, the evolution of the West African subtype of variola virus led to a reduction in the case fatality rate of smallpox from 12% to less than 1%.

Based on data from restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, it was confirmed that variola minor alastrim originated from the West African strains of the virus. Furthermore, it was calculated that the rate of mutation accumulation in these viruses amounts to 0.9-1.2 x 10-6 substitutions per site per year.

Phylogenetic reconstructions suggest that the camelpox virus, taterapox virus, and variola virus emerged from a common progenitor almost simultaneously. Additionally, these viruses are strictly specific for their hosts, and both the variola and camelpox viruses cause diseases with high case fatality rates.

The evolution of clinical presentation

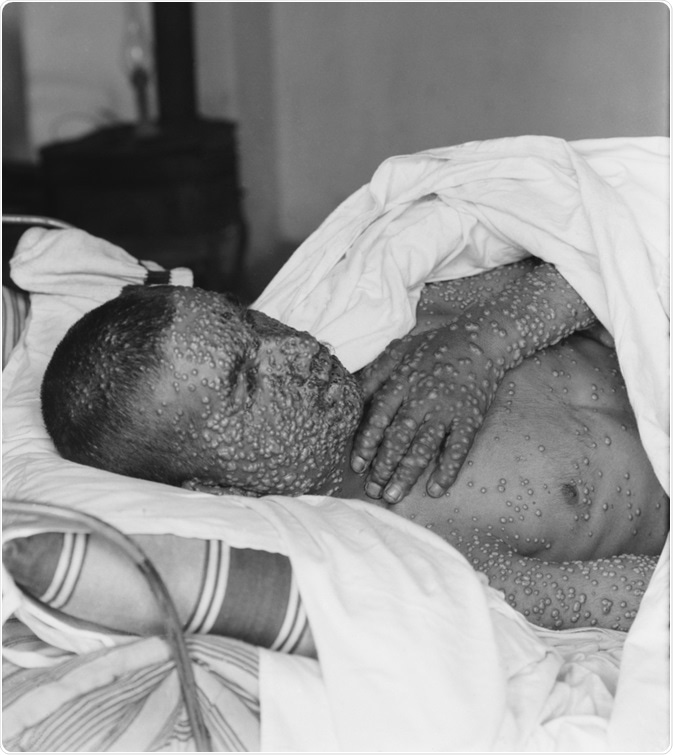

Upon infection with the variola virus, approximately 90% of unvaccinated individuals used to develop ordinary smallpox, characterized by an incubation period from 7 to 17 days, a 2-3-day flulike prodrome characterized by severe headache, backache and fever, and a centrifugally distributed rash.

Almost one-half of these patients exhibited a disease type where pocks were sufficiently low in number to remain separated by normal skin. The rest of the affected individuals developed a more serious illness, where a larger number of lesions became confluent in certain areas.

Image Credit: Everett Collection / Shutterstock.com

The mortality rate for ordinary smallpox differed according to the number of skin lesions - ranging from approximately 10% for discrete disease to almost 30% for confluent disease. In fatal cases, hypotension and fever progressed to steadily worsening shock.

Clinical descriptions of the disease indicate that smallpox always had a high case-fatality rate until around the end of the 19th century when a more benign form of the disease, which caused a similar rash but a substantially lower mortality rate, emerged in the Western Hemisphere.

Such less-lethal types of smallpox were also seen in Africa, where they may have existed for some time. These milder variants are now known as “variola minor,” in contrast to the traditional form of the disease known as “variola major.” Disease severity was also determined by the propensity of host responses to limit viral replication during the incubation period.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Mar 28, 2021