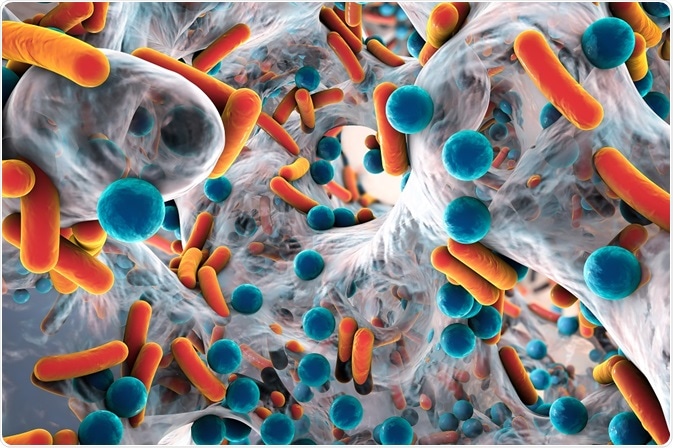

The microbiome is the collection of bacteria, fungi and viruses present on and within the human body. The total number of microbial cells far outweigh our own, with an estimated ratio of 10:1 for bacteria.

Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

The microbiome is a vital part of many bodily systems, including the digestive system, the immune system, and the skin. The cells of the microbiome interact with the host cells in each system, influencing health and development.

Host-cell interactions with the microbiome

The composition and activity of the microbiome co-develops with the host human from birth, and is subject to complex interactions that depend on the host nutrition, genetic make-up, and general lifestyle.

The gut microbiota is involved in the regulation of numerous human metabolic pathways, giving rise to host cell-microbiota interactions via metabolic, signalling, and immune-inflammatory pathways that physically connect the liver, muscle, gut, and brain.

A deeper understanding of these interactions can assist in the development and optimization of therapeutic strategies in which medications can manipulate the microbiome to combat disease and improve general health.

The human gut microbiome can be helpful in digestion, but can also exacerbate inflammatory gut diseases. One pathway where the microbiome has an effect on GI inflammatory disease is by causing changes to the metabolism of the host.

The human metabolism is connected with the metabolism of the intestinal microbiome. For example, humans depend on their own microbiome bacteria to make several key vitamins, which include folate, biotin, vitamin B6, vitamin B5, thiamine, and riboflavin.

These members of the microbiome can also drive intestinal disease through alterations in how the microbiome is structured, the disruption of the mucosal layers, the interactions with the innate and adaptive immunity, and the bad effects on the enteric nervous system.

Human microbiome can also stimulate the host immune system to respond more quickly to pathogen infection and, through bacterial antagonism, prevents the colonization of the GI tract by these pathogens.

Bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, however, are also opportunistic pathogens, which can move across the mucosal barrier to cause infection in hosts which are, in some way, immunologically deficient (e.g. HIV patients, the elderly, etc).

The biochemical signalling between the GI tract (including the GI microbiome) and the brain has only been studied in recent years, but has been found to be vital for maintaining certain types of bodily homeostasis, and is regulated at both the central and enteric nervous systems, as well as via hormones, and through immunological pathways.

Medicines that affect microbiome-host cell interactions

Probiotics are one of the current medicinal methods used to adjust the GI microbiome in a way that benefits the host. However, the functional effects of probiotics cannot be assessed properly without studying the biochemistry of the host.

Other medications which can be used to adjust the microbiome (and therefore the microbiome-host interactions) are proton pump inhibitors. These are among the top 10 most widely used drugs in the world, with their use being associated with an increased risk of GI infections.

The gut microbiome plays an important role in these infections, by resisting (or sometimes promoting) infection by these enteric pathogens. When proton pump inhibitors are used, many studies have showed significant changes in the human gut microbiome.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019