Aug 7 2015

Scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have shown how aging cripples the production of new immune cells, decreasing the immune system’s response to vaccines and putting the elderly at risk of infection. The study goes on to show that antioxidants in the diet slow this damaging process.

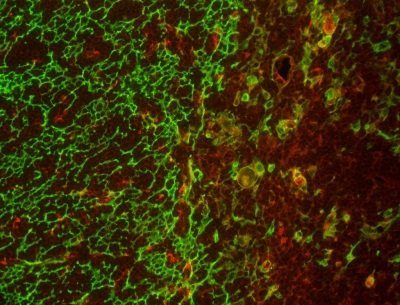

The Scripps Research Institute team found that stromal cells (green) in the thymus were deficient in an antioxidant enzyme called catalase (red), resulting in accelerated metabolic damage.

The research, published August 6 in the journal Cell Reports, focused on an organ called the thymus, which produces T lymphocytes, critical immune cells that must be continuously replenished to respond to new infections.

“The thymus begins to atrophy rapidly in very early adulthood, simultaneously losing its function,” said TSRI Professor Howard Petrie. “This new study shows for the first time a mechanism for the long-suspected connection between normal immune function and antioxidants.”

Scientists have been hampered in their efforts to develop specific immune therapies for the elderly by a lack of knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of this process.

To explore these mechanisms, Dr. Petrie and his team developed a computational approach for analyzing the activity of genes in two major thymic cell types—stromal cells and lymphoid cells—in mouse tissues, which are similar to human tissues in terms of function and age-related atrophy. The team found that stromal cells were specifically deficient in an antioxidant enzyme called catalase, which resulted in elevated levels of the reactive oxygen by-products of metabolism and, subsequently, accelerated metabolic damage.

To confirm the central role of catalase, the scientists increased levels of this enzyme in genetically altered animal models, resulting in preservation of thymus size for a much longer period. In addition, animals that were given two common dietary antioxidants, including vitamin C, were also protected from the effects of aging on the thymus.

Taken together, the findings provide support for the “free-radical theory” of aging, which proposes that reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide, produced during normal metabolism, cause cellular damage that contributes to aging and age-related diseases.

While other studies have suggested that sex hormones, particularly androgens such as testosterone, play a major role in the aging process, they've failed to answer the key question—why does the thymus atrophy so much more rapidly than other body tissues?

“There’s no question that the thymus is remarkably responsive to androgens,” Dr. Petrie noted, “but our study shows that the fundamental mechanism of aging in the thymus, namely accumulated metabolic damage, is the same as in other body tissues. However, the process is accelerated in the thymus by a deficiency in the essential protective effects of catalase, which is found at higher levels in almost all other body tissues.”