The study brought to light the potential widespread of mosquitos and gaps in the capabilities of local surveillance, both of which are vital to understand the threat of Zika and other mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and chikungunya.

In 2015, a survey of vector-control professionals, entomologists, and state and local health departments was conducted at county level and another survey was carried out in 2016. CDC has compiled the county-level records that show the distribution of Ae. Aegypti in 220 counties across 28 states and the District of Columbia (DC), and Ae.Albopictus in 1368 counties across 40 states and in the DC. The CDC researchers said that the data collected was their best knowledge regarding the distribution of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus across the U.S. during the period 1995–2016.

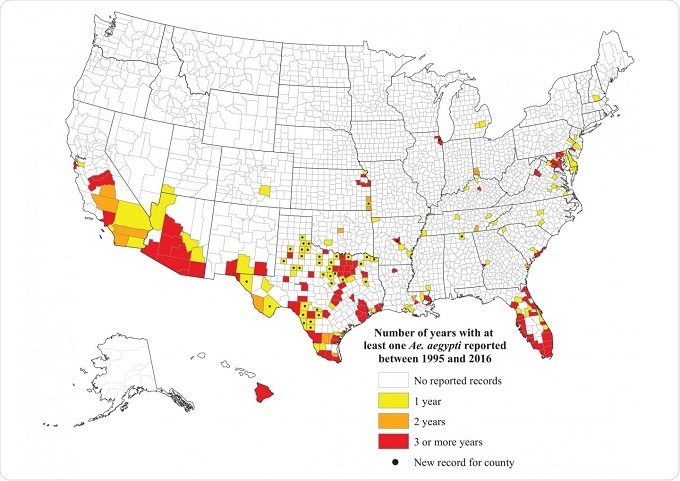

Image: A county-level survey conducted in 2015 and 2016 by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows the historic occurrence of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes between January 1995 and December 2016 in the United States. Counties with black dots had new, previously unreported surveillance records in the second round of the survey in 2016, reflecting increased attention on surveillance for mosquitoes. 'Prompted by the Zika outbreak, states began work to better assess the distribution and abundance of these mosquitoes, locally,' says Rebecca Eisen, Ph.D., research biologist with CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases. (Note: The map indicates presence, not abundance, of Ae. aegypti, and the map does not indicate levels of risk for the spread of any specific disease.) Credit: CDC

Moreover, in some places the data revealed the presence of mosquitos in higher percentages during the period 1995–2016, which the researchers attributed to the increased awareness of Zika threats and the risks posed by other diseases, and not to any unexpected spread of the mosquitoes.

Prompted by the Zika outbreak, states began work to better assess the distribution and abundance of these mosquitoes, locally. The updated survey CDC conducted in fall 2016 demonstrated that intensified surveillance in the summer of 2016 resulted in Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus being collected in many counties where there were no records for them in recent decades."

Rebecca Eisen, Ph.D., research biologist with CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases and co-author of the study.

Eisen said that the findings showed gaps in the distribution of the mosquitos, probably due to lack of local surveillance. She emphasized that the study demonstrates the presence of the species, and not their abundance or the threat of the spread of Zika or any other disease. She also mentioned that the information would assist in targeting the limited public health surveillance resources and help to improve their understanding on the widespread presence of these mosquitoes.

Counties should collect a minimum of one sample of the mosquito in any stage of its life cycle in a given calendar year using any collection method for the survey. Then the mosquito species is considered to be present in that county during that year.

The Ae. aegypti species was reported to be present in all the southern U.S. states. Most of the county reports came from southern California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. However, county collection reports from Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina were more sporadic.

While the distribution of Ae. Albopictus was recorded in a few counties in the Southwest, including California, Arizona, and New Mexico, it was found to be higher and more regular in the Southeast and mid-Atlantic states and in southern New England.

The study findings neither show the number of mosquitoes present in an area nor their exact location. Yet the data help CDC and local stakeholders to provide improved direct surveillance and control efforts.

For example, in counties where Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus have not been reported, but are recorded in neighboring counties, CDC can create climate suitability models for these important mosquito vectors.

The study was published online in the Journal of Medical Entomology on June 19.

Sources:

- https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-06/esoa-ncd061217.php

- https://academic.oup.com/jme/article/3868585/Updated-Reported-Distribution-of-Aedes-Stegomyia?searchresult=1