Sep 24 2018

When people take MDMA, the drug popularly known as ecstasy, a rush of serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin produces feelings of emotional closeness and euphoria, making people more interested than they would normally be in connecting and sharing with other people. Now, researchers reporting in Current Biology on September 20 have made the surprising discovery that a species of octopus considered to be primarily solitary and asocial responds to MDMA in a similar manner: by becoming much more interested than usual in engaging with one other.

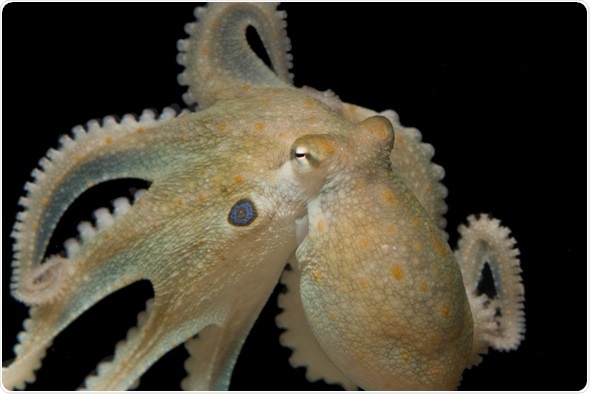

This image shows a California two-spot octopus (O. bimaculoides). Credit: Thomas Kleindinst

"Despite anatomical differences between octopus and human brain, we've shown that there are molecular similarities in the serotonin transporter gene," says Gül Dölen of Johns Hopkins University, noting that the gene encodes a transmembrane protein that serves as the primary binding site for MDMA. "These molecular similarities are sufficient to enable MDMA to induce prosocial behaviors in octopuses."

Dölen and the study's first author, Eric Edsinger, chose to study Octopus bimaculoides because it's possible to breed and study their behavior in the lab. It's also the only octopus to have its genome fully sequenced. That allowed the team to make comparisons between the genes in octopuses and humans.

Octopus and human lineages are separated by more than 500 million years of evolution, and yet their genomic analyses showed that O. bimaculoides has the serotonin transporter gene known to serve as the principle binding site of MDMA. The findings added to evidence that ancient neurotransmitter systems are shared across vertebrate and invertebrate species. The discovery also suggested that the octopuses had the molecular components needed to sense and potentially respond to MDMA.

But was it possible that the relatively asocial octopuses actually might show a behavioral response to MDMA similar to people? To find out, Dölen and Edsinger tested the octopuses' interest in other octopuses compared to novel objects under normal circumstances. Those studies showed the octopuses actually do have more interest in each other, and particularly in other females, than had often been thought.

Next, they tested the octopuses' interest in each other again while under the influence of MDMA. And what they saw surprised them. The octopuses not only spent more time with other octopus individuals including other males while on the drug, but they also engaged in extensive ventral surface contact. That unusual physical contact between individuals appeared exploratory, not aggressive, in nature.

The findings show that despite being evolutionarily distant from invertebrate species like octopuses, humans share a common evolutionary heritage that enables serotonin to encode social behaviors, the researchers say. They add that the octopuses may rely on common pathways to behave socially at certain times, such as during mating season.

The researchers are now in the process of sequencing the genomes of two other species of octopus, which are closely related to each other but differ in their behaviors. By comparing the genomes of those species, they hope to gain more insight into the evolution of social behavior.