Does an open relationship actually make sense, is today’s hot question, it seems, judging from a report in the Journal of Sex Research by a team of researchers from the University of Rochester. The only answer they got was that it depends – not unsurprisingly, on how well the ‘partners’ in such a relationship knew each other’s intentions and were okay with them.

Past studies have attempted to gauge the success of nonmonogamous relationships. Now a Rochester team has studied the distinctions and nuances within various types of nonmonogamous relationships and found that solid communication is key. Image Credit: Patricia Chumillas / Shutterstock

The postmodern world is possibly the first time open relationships have become an accepted ‘other’ type of romantic relationship. Here, both partners knowingly and consensually engage in outside sexual activity. However, this study fails to show distinct advantages for such relationships over more time-tested monogamous relationships, while bringing out certain important disadvantages.

Researcher Ronald Rogge says, “It is critical for couples in nonmonogamous relationships as they navigate the extra challenges of maintaining a nontraditional relationship in a monogamy-dominated culture.” What he means is that each partner needs to keep the other in the loop as they pursue sexual satisfaction with other people. He continues, “Secrecy surrounding sexual activity with others can all too easily become toxic and lead to feelings of neglect, insecurity, rejection, jealousy, and betrayal, even in nonmonogamous relationships.”

This is not the first study on relationships that are not one-on-one, but this time around, the scientists looked at differences between various types of nonmonogamous relationships to classify them as successful or unsuccessful independently. The result is a set of observations as to the conditions which should be met to maximize the chances of success in this relationship.

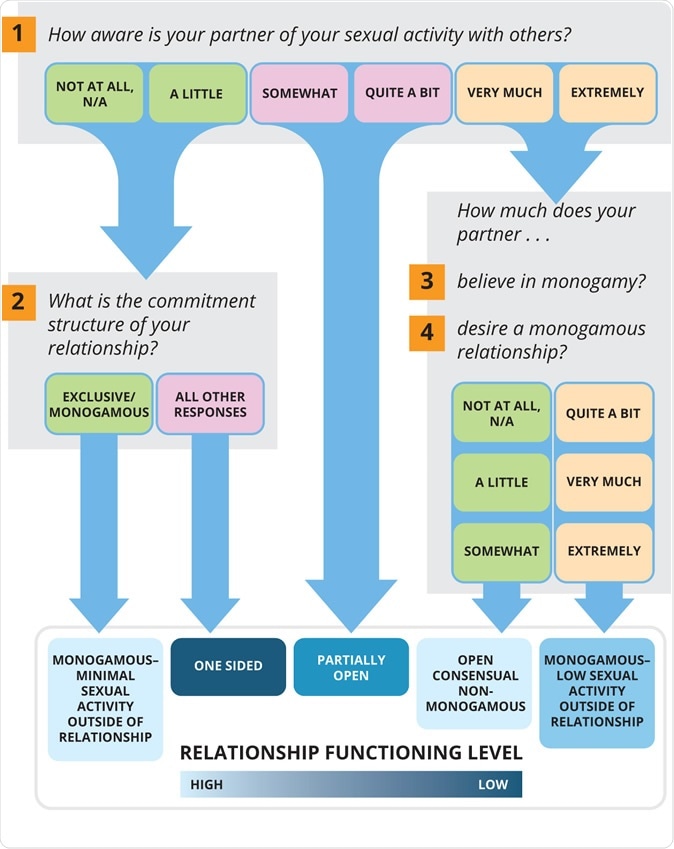

(University of Rochester illustration / Michael Osadciw)

The study

The researchers looked at answers to about 1700 questionnaires distributed online. Two-thirds were in the second or third decade of life, and almost 80% were white. 70% were female, and most of them reported being in long-term relationships for 4.5 years on average.

The study examined three aspects of the relationships, namely, mutual consent, communication and comfort. Based on these results, they classified participating adults into five relationship categories

- Early monogamous relationships

- Late monogamous relationships

- Consensual nonmonogamous (CNM) relationships – the partners were both interested in, comfortable with and consenting to sexual activity with others outside the relationship on both sides, and neither kept such activity a secret from the other

- Partially open relationships – here both partners were at different levels of comfort, consent and communication around outside sexual activity, and the desire for monogamy was non-uniformly shared by both

- One-sided nonmonogamous relationships – here only one partner actively engaged in outside sex, and the other partner wanted a monogamous relationship; they almost never talked about the outside sexual activity by one partner, while comfort and consent levels were also low

What’s good

Not surprisingly, both monogamous groups, as well as the CNM group, expressed high functioning relationships. They had among the least frequent feelings of loneliness or mental distress. They also reported high satisfaction with the way their needs were met, including sexual needs, and relationship needs, in almost 80% of cases. Earlier studies have reported both equal and reduced levels of happiness within CNM compared to monogamous relationships, and this area requires further research.

Monogamous couples reported relatively low needs to seek new thrills in sexual experience, indicating they were quite comfortable with a low-key attitude to sex outside such a relationship.

Among these, CNM couples had long-term relationships that lasted longer than the other two nonmonogamous couples. In fact, these were the most likely to be living with their partner, though the monogamous group with the greatest faithfulness within the relationship were a close second.

What’s bad

However, nonmonogamous couples were at risk in several different ways for sexual dissatisfaction, sexually transmitted disease (STD)s, and seeking casual sex. They had high overall levels of the need to experience new sensations during sex, searched for new partners more often, and had a higher rate of STDs.

CNM group couples also consisted of many more individuals described as heteroflexible, which denotes that they could be mainly interested in the opposite sex but open to same-sex partners as well) or bisexual (equally attracted to both sexes). This could explain why LGBT partners adopt such structures in opposition to monogamy. Previous studies have also shown that LGBT couples are overrepresented in this category.

As expected, the one-sided groups fared the worst. Significantly, these were the youngest, which may show that younger people don’t have the maturity or experience to choose what is best for them. They were also less attached to each other and less affectionate. Sexual satisfaction was low, and high-risk sexual behavior was high (having intercourse with new partners without condom use).

Those in which one partner was cheating on the other were prototypes of bad relationships, with 60% of partners saying they were not satisfied. This is almost threefold the rate of monogamous or CNM groups.

Limitations and implications

This is a snapshot study, which means the authors don’t know what happened to the relationships over time. However, a cross-sectional view clearly shows what couples have always known: “Sexual activity with someone else besides the primary partner, without mutual consent, comfort, or communication can easily be understood as a form of betrayal or cheating. And that, understandably, can seriously undermine or jeopardize the relationship.” (Forrest Hangen).

On the other hand, long-term follow up is crucial in a study of this kind which affects entire lifestyles, because short-term happiness and satisfaction may not mirror long-term consequences which in turn have a heavy impact on long-term satisfaction with the lifestyle that is finally followed. Many studies seem to focus only on sexual satisfaction which is, after all, only a small component of relationship happiness, and which is not lacking in monogamous relationships. It is always important, in psychology as well as in any other field of research, to make sure that an innovation is really better than the previous version, before adopting it.

Source:

Journal reference:

Open Relationships, Nonconsensual Nonmonogamy, and Monogamy Among U.S. Adults: Findings from the 2012 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. Ethan Czuy Levine, Debby Herbenick, Omar Martinez, Tsung-Chieh Fu, and Brian Dodge. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2018 Jul; 47(5): 1439–1450. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00224499.2019.1669133