University of Groningen scientists observed the characteristics of a single enzyme inside a nanopore. This revealed that the enzyme can exist in four different folded states, or conformers, that play an active role in the reaction mechanism. These results will have consequences for enzyme engineering and the development of inhibitors. The study was published in Nature Chemistry on 6 April.

Image Credits: Giovanni Maglia, University of Groningen / EurekAlert.com

Image Credits: Giovanni Maglia, University of Groningen / EurekAlert.com

Enzymes are folded proteins that have a specific three-dimensional structure that creates an active site that can bind a substrate and catalyse a specific reaction. In recent years, it has become clear that enzymes are not rigid structures but that the folded proteins exist as an ensemble of conformations in equilibrium around an energetically stable ground state.

Wind tunnel

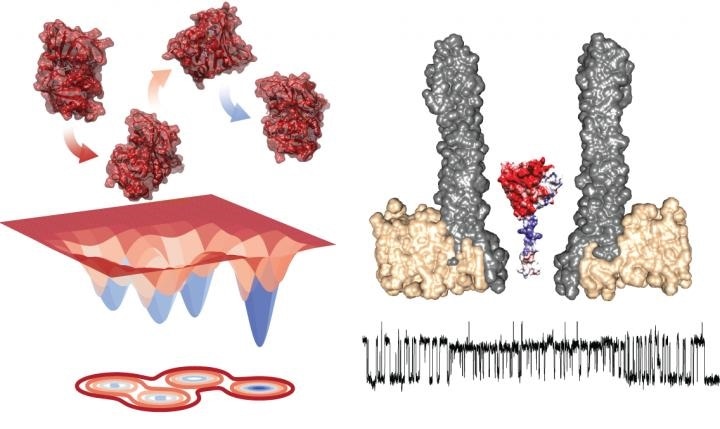

Studying the transition between states requires observing single enzymes for a prolonged period of time, which is challenging. University of Groningen Associate Professor of Chemical Biology Giovanni Maglia developed funnel-shaped nanopores that can trap proteins.

By measuring the ionic current across such a nanopore, embedded in an artificial lipid membrane, Maglia was able to observe conformational changes in enzymes. 'You could compare it with studying a car in a wind tunnel,' he explains. 'Opening a window or a door will change the airflow. In a similar way, a change in the folding structure of the enzyme changes the ionic current through the pore.'

Maglia used his nanopore system to study the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which converts dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate.

We chose this enzyme because it has been studied as a model system for enzyme dynamics for over thirty years, using all available techniques. In addition, inhibitors of this enzyme, such as methotrexate, are used as anti-cancer drugs."

Giovanni Maglia, University of Groningen

Efficient release

Measurements of DHFR revealed the presence of four different conformers, with different affinities for the substrates. Maglia: 'Switching between these four states was very slow. This means that you can only see them in these kinds of long-lasting single enzyme studies.'

Adding the reaction inhibitor methotrexate, which binds to the enzyme, caused a very rapid transition between states and changed the enzymes' affinity. 'Our conclusion is that the reactions of the enzyme with different compounds provide the free energy for conformational changes,' says Maglia.

Furthermore, conformational change also changed the enzymes' affinity. This makes sense, as the enzyme needs to bind two substrates and, after completing the reaction, must release both. 'The substrate and the product are very similar molecules, so the enzyme needs to change its affinity for an efficient release.'

Two states

Based on these studies, Maglia can see the enzyme switching between two states: after binding the substrate, NADPH drives the reaction which then changes the conformation of the enzyme and thereby its affinity. Subsequently, binding a new substrate brings it back to the first state. 'This explains two of the four conformers that we observed; we cannot yet make sense of the other two,' Maglia admits. It is impossible to derive structural information from the measurements.

Nevertheless, the study shows the power of nanopore technology in determining the structural changes of enzymes. 'We also now know that this enzyme has four different ground states and must switch between them to function.' This adds a challenge to enzyme design: not only should this produce a reactive centre, but it should also allow the necessary conformational changes.

This may explain why artificially designed enzymes often do not work as efficiently as natural enzymes.'"

Giovanni Maglia, University of Groningen

Finally, the study will also allow scientists to identify new inhibiting drugs that bind tighter to DHFR than methotrexate.