These findings could potentially help control COVID-19’s spread by facilitating early diagnosis and making it possible to practice effective social isolation measures earlier.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Importance of early identification of asymptomatic infection

Asymptomatic carriage of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, has been one of the limiting factors for the efficient containment of viral spread in the current pandemic. Individuals infected with the virus need to be identified and isolated rapidly (and in a cost-efficient manner) to restrict SARS-CoV-2’s transmission. To do this, it is necessary to both identify and understand the clinical manifestations of this disease. This is especially valuable given the current shortfall in testing kits in many parts of the world.

Alterations in taste or smell are thought to be present in about 80% of COVID-19 cases in Europe. This development is possibly linked to viral entry into angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)-bearing epithelial cells, including the olfactory epithelium in the upper part of the nasal cavity. The ACE2 receptor is the site at which the spike protein of the virus gains entry into the host cell to commence viral replication. This development could be associated with damage to nasal and brain cells.

Goblet cell targets of SARS-CoV-2

Goblet cells, which are found scattered among epithelia in the respiratory and intestinal tract, are viral targets, since they express ACE2. These mucin-producing cells are also in the respiratory epithelium of the nose. The breakdown of the mucin barrier by the action of the virus on the goblet cells could also contribute to the anosmia/hyposmia, since the odorant molecules may probably stick to their receptors with the help of the mucus.

Mucus reduction could also cause strange sensations in the nasal cavity, in which case virus-induced this could also herald COVID-19 earlier than other symptoms.

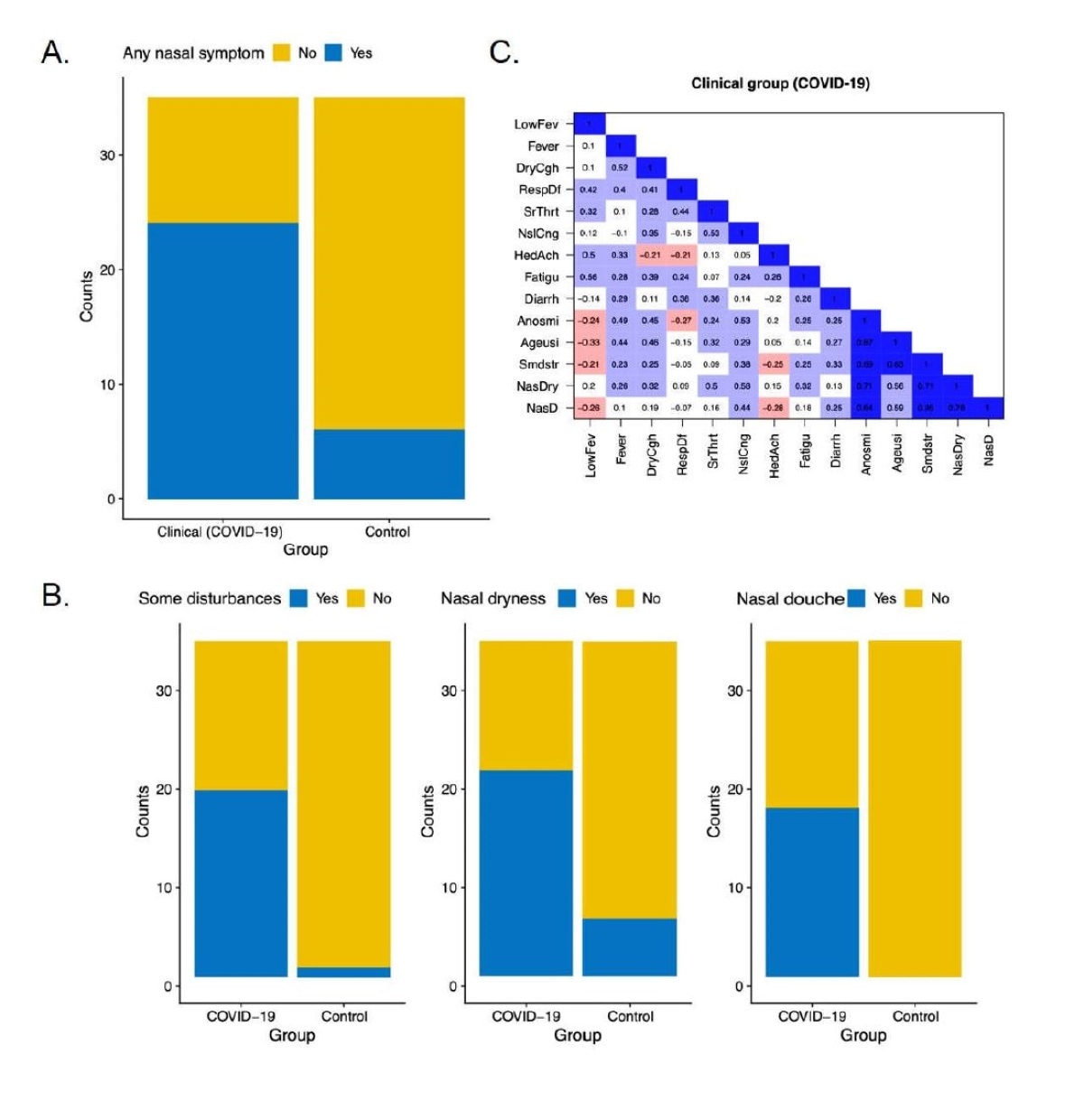

The current study sought to determine if these changes were possibly linked to other symptoms that could explain them. The researchers explored nasal symptoms in a group of 35 patients, including only those which could possibly cause marked disruptions in olfactory function. They validated their observations with a control group of similar age and sex composition.

Unusual nasal symptoms

They found that almost 70% of the patient group said they had one or more nasal symptoms, including “a strange sensation in the nose,” almost 37 times more often than the control group.

Over 60% said they felt an abnormal dryness of the nose versus around 15% of controls. Additionally, over half of the patient group said they felt as if a strong nasal wash had been administered, while only one member of the control group reported this sensation, making the patient group risk 32-fold higher for this symptom.

In the patient group, the nasal symptoms mostly occurred in the same period as the alteration in smell and taste, or before the latter began. The mean period of such symptoms was 12 days, on average, versus 5 days in controls. Overall, about 85% and 80% of the patients had issues with loss of smell and taste, respectively, which is congruent with other reports on the subject.

Distribution of subjective “nasal” symptoms in each group, and correlations between nasal and other symptoms. The clinical and control groups differed statistically in (A) the presence of nasal symptoms in general. (B) The 2 groups also differed in their subjective perception of three different “nasal” symptoms: Some nasal disturbances, nose dryness, and nasal douche sensation. (C) Co-occurrence matrices of symptoms for the clinical group (COVID-19). LowFev=Low grade fever; DryCgh=Dry cough; RespDf=Respiratory difficulties; SrThrt=Sore throat; NslCng=Nasal congestion; HedAch=Headache; Fatigu=Fatigue; Diarrh=Diarrhea; Anosmi=Anosmia; Ageusi=Ageusia; Smdstr=Some disturbances; NasDry=Nasal Dryness; NasFl=Nasal Flush.

The importance of these findings is not that they are life-threatening, or contribute to the morbidity, but that they are 1) distinct from anosmia or ageusia, and 2) present early in the course of the illness. This may signal that they should be included in early diagnosis protocols for COVID-19, such as early monitoring and adjusted social isolation measures to prevent transmission.

What are the implications?

These clinical findings may be related mechanistically, as described in the above hypotheses. The entry of the virus into the respiratory nasal epithelium, especially the goblet cells, may cause a sudden disruption of the mucus barrier, which in turn causes the epithelium to dry out. This also reduces olfactory sensitivity by decreasing the number of odorant molecules that can adhere to their receptors, in the absence of the sticky mucus layer. This could account for both the aberrant nasal sensations and the loss of smell.

Of course, the viral infection could also cause direct damage to the respiratory epithelium. This could be a topic for further research, which could pinpoint the exact point in time at which the abnormal nasal sensations, such as excessive nasal dryness, give way to other symptoms of COVID-19 that are more widely recognized.

The researchers conclude, “The presence of these nasal sensations could be taken into account for both diagnostic and social distancing purposes, especially in those situations in which RT-PCR tests cannot be administered to non-severe cases.”

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.