The continuing spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) globally has not only taken a great toll on human health but threatens the economic stability of the human race. SARS-CoV-2, which is the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is unpredictable in its effects, as it has the potential to cause devastating disease in some while leaving most individuals asymptomatic or with a very mild form of the infection.

Study: Combustible and electronic cigarette exposures increase ace2 activity and SARS-CoV-2 spike binding. Image Credit: esthermm / Shutterstock.com

Study: Combustible and electronic cigarette exposures increase ace2 activity and SARS-CoV-2 spike binding. Image Credit: esthermm / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

SARS-CoV-2 engages with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) host cell receptor, which is found in two forms within the lung. One form of ACE2 is membrane-attached (mACE2), whereas the other is a soluble form of ACE2 (sACE2). Of these, mACE2 is the binding site utilized by SARS-CoV-2 prior to its entry into the host cell.

The role of tobacco smoking as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 has been controversial. Some scientists consider it to increase the risk of infection and the severity of the disease. Similarly, vaping, or the use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) has also been shown to cause toxicity in the lung tissue via the synthesis of noxious proteins as well as through immunologic alterations.

The nicotinic hypothesis, as it is called, postulates that nicotine can be protective against infection by SARS-CoV-2. On the other hand, some scientists have also reported a strong link to exist between smoking and symptomatic COVID-19, especially since smoking increases the risk for influenza and other respiratory viruses.

Higher levels of ACE2 in smokers were thought to be responsible for this increased risk.

Higher ACE2 levels in lung fluid

In the current study, scientists found that washings from the small airways of the lungs, which are otherwise referred to as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), from smokers and vapers showed markedly higher levels of sACE2 as compared to non-smokers of the same age. They also found that in cell cultures of primary human bronchial epithelial cultures (HBECs) that were grown to simulate the human airway, exposure to cigarette smoke for just one day led to a significant increase in both mACE2 and sACE2 levels.

Over a period of four days of smoke exposure, which was meant to reflect chronic smoking, both the levels of mACE2 and sACE2 continued to be significantly higher as compared to cell cultures that were exposed to air alone. Thus, smoke exposure appears to increase the number of ACE2 receptors on host cells that are available for the virus to latch on to.

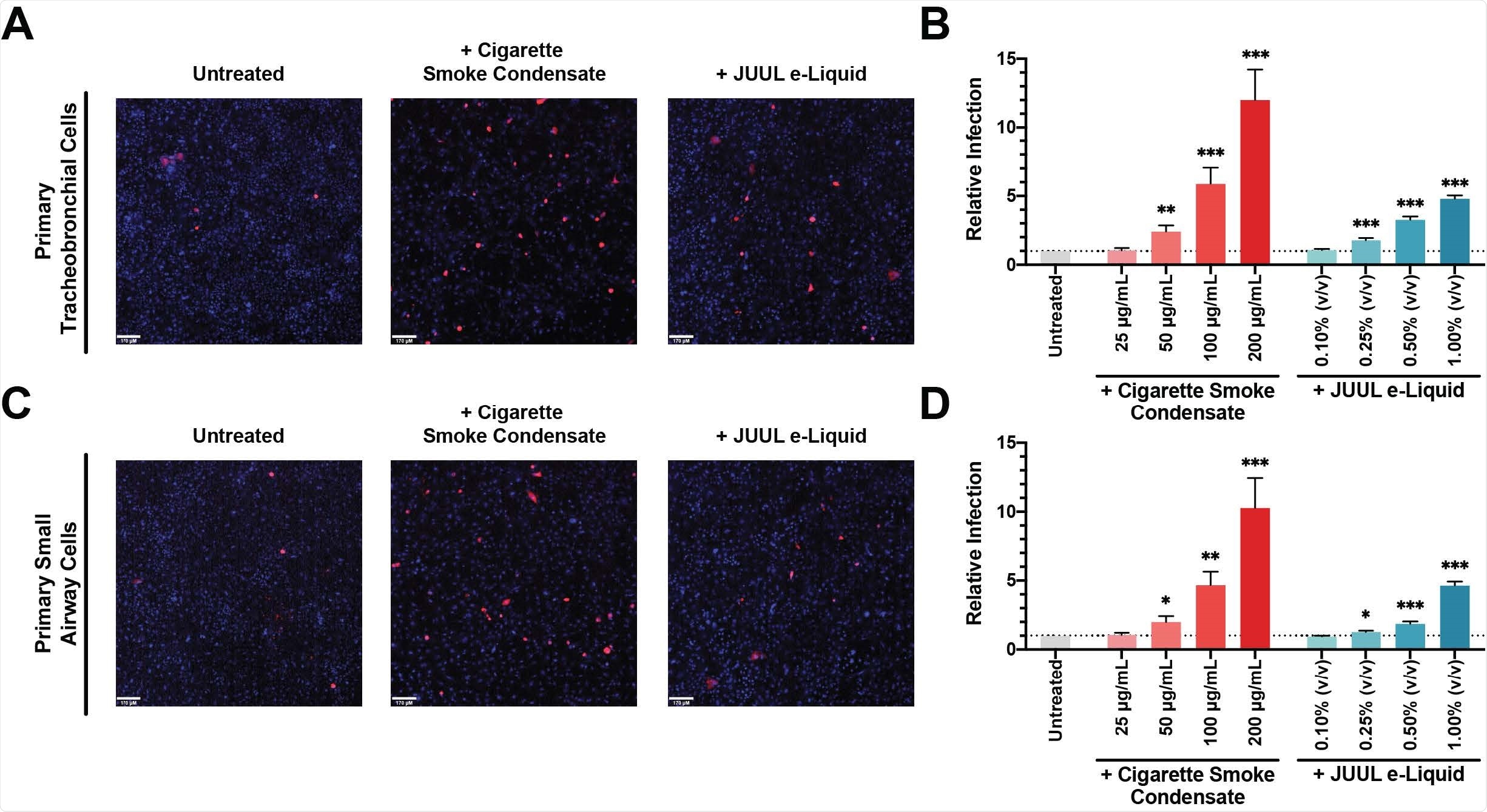

Cigarette Smoke Condensate Exposure Increases SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Infection. Primary tracheobronchial (A) and small airway cells (C) were pre-treated with 200 μg/mL CSC (middle) and 1.00% JUUL e-Liquid (right) for 24 hours and challenged with SARSCoV-2 pseudovirus. Following incubation for 48 hours, live cells were imaged on a spinning-disc confocal microscopy system (UltraVIEW Vox; PerkinElmer). Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye and infected cells were shown in red. Flow cytometry quantification of relative SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus infection in different doses of CSC and JUUL e-Liquid pre-treated primary tracheobronchial cells (B) and small airway cells (D) were reported as fold change; n = 11-12 trials. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Unpaired t test * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.0005. Scale bars, 170 μm.

Higher rates of infection

Simultaneously, the study also showed that cells exposed to both acute and chronic smoke experienced higher rates of infection with a pseudovirus bearing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They also showed significantly higher rates of S1 subunit uptake.

Vape liquid produces similar effects

When airway epithelial cells were exposed to different doses of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) for one day, pseudovirus infection rates increased significantly when compared to controls. The same observation was documented when cells were exposed to the e-liquid from JUUL Virginia Tobacco-flavored vapes, which contains 5% nicotine benzoate.

Chronic exposure over a period of four days also produced the same result. Taken together, these findings provide in vivo evidence that the use of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes is associated with higher rates of infection by the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

“These data indicate that cigarette smoke exposure upregulates ACE2 activity and increases SARS-CoV-2 binding.”

Soluble ACE2 is a risk marker for COVID-19

The current study only measured sACE2, rather than mACE2, in vivo. Notably, sACE2 also plays a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection through its effects on the renin-angiotensin system. The increase in sACE2 levels, as well as the overall higher number of ACE2 present within the lung cells of both smokers and vapers, is thought to be a contributing factor in the higher risk of infection for individuals in these categories.

Indeed, lung cells in smokers exhibit higher levels of ACE2 gene transcription, which may indicate increased levels of both types of ACE2. The high sACE2 levels have also been shown to be linked to increased severity of disease following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, sACE2 elevation can be used as a biomarker for individuals who are at an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19.

What are the implications?

These findings point to a strong link between ACE2 levels in lung cells and both tobacco smoking and vaping. Although there has been some speculation that this link is mediated by nicotine, further studies should still be conducted to confirm this hypothesis. Moreover, the rise in total ACE2 levels may be prolonged beyond the period of smoking, thus increasing the risk that the smoker will contract the infection.

“Overall, these observations indicate that tobacco product use elevates ACE2 activity and increases the potential for SARS-CoV-2 infection through enhanced spike protein binding.”

Nicotine is present in tobacco smoke as well as in vapes. This molecule is responsible for an increase in intracellular calcium which, in turn, is known to promote viral entry, replication, and the release of new viral particles. Nicotine may therefore be the common factor that is responsible for the increase in both spike protein binding and pseudovirus infection following tobacco smoke exposure.

More research is needed to fully understand how this chemical causes this effect and the extent to which elevated levels of ACE2 and spike binding persist in the lungs of smokers.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Ghosh, A., Girish, V., Yuan, M. T., et al. (2021). Combustible and electronic cigarette exposures increase ace2 activity and SARS-CoV-2 spike binding. bioRxiv preprint. doi:10.1101/2021.06.04.447156. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.04.447156v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Ghosh, Arunava, Vishruth Girish, Monet Lou Yuan, Raymond D. Coakley, Joe A. Wrennall, Neil E. Alexis, Erin L. Sausville, et al. 2022. “Combustible and Electronic Cigarette Exposures Increase ACE2 Activity and SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding.” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 205 (1): 129–33. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202106-1377le. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202106-1377LE.