The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is characterized by protean manifestations, leading to both acute and chronic inflammatory processes in multiple organs. Among the most serious of these are the neurologic sequelae.

Study: Anti–SARS-CoV-2 and Autoantibody Profiles in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of 3 Teenaged Patients With COVID-19 and Subacute Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock.com

Study: Anti–SARS-CoV-2 and Autoantibody Profiles in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of 3 Teenaged Patients With COVID-19 and Subacute Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock.com

Background

Over 245 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide, of which over 6.2 million cases have been reported in children. Typically, children with COVID-19 will experience a mostly mild respiratory disease; however, they may suffer from other complications including neurological sequelae. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), for example, is a recognized complication following infection with SARS-CoV-2.

About a fifth of children with MIS-C develop neurologic features such as encephalitis, seizures, aseptic meningitis, and confusion. In adults, post-COVID-19 sequelae include new or recurrent episodes of psychiatric illness, with a higher incidence than in cases of influenza and other respiratory infections.

The central nervous system (CNS), which consists of the brain and spinal cord, are bathed in CSF. CSF has been sampled for testing in COVID-19 patients to look for viral nucleic acid in the form of ribonucleic acid (RNA). The results have been mostly negative.

In a few cases, however, antibodies to the virus have been reported in CSF samples, a sign of potential invasion of the CNS. Autoantibodies to neural antigens have also been reported in a few adults with neurologic impairment following COVID-19.

The current study focuses on children with COVID-19 who have experienced neurological and/or psychiatric manifestations, as well as those whose samples have been detected with intrathecal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 or to neural antigens.

Study findings

The three adolescents in the current study presented with neuropsychiatric symptoms and were found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 on either reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing or serology. All patients experienced subacute behavioral changes that impaired their functioning and accompanied the infection.

Patient 1

Patient 1 was a teenage marijuana user who had received some psychiatric care for anxiety and depression. At presentation, the patient showed signs of social withdrawal, sleeplessness, unpredictable behavior, and paranoid fears. Urine testing also showed evidence of marijuana use. Though RT-PCR-positive, the patient did not experience any respiratory symptoms.

The patient was discharged after two weeks on antipsychotic drugs but returned with paranoia and delusion, accompanied by asymmetric hyperreflexia of the legs. Again, the patient had used marijuana. Intrathecal protein and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies were elevated; however, autoantibodies were not found in blood or CSF.

Other tests, including brain imaging, were negative. Considering the subacute symptoms and CSF findings, the suspicion of inflammatory disease was strong. The patient was therefore treated with a three-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin, and subsequently of methylprednisolone, which was tapered over the next few days.

On the 20th day after the initial onset of symptoms, coinciding with the fifth day from the start of immunoglobulin therapy, clinical improvement was visible in terms of clearer thinking, less paranoia, and enhanced insight. At the end of a month, the patient was no longer delusional and their hyperreflexia had resolved; however, the patient was still showing emotional lability, as a result of which the patient was sent home on valproate.

Patient 2

The second patient had anxiety, motor tics, and brain fog. With a family contact who was COVID-19-positive, the patient developed fever and respiratory symptoms five days later. Following a spontaneous recovery, the patient then found it difficult to find the right words, could not concentrate, and was unable to complete homework, along with labile moods and insomnia.

Over the next 1.5 months, the patient showed a preoccupation with internal stimuli, became aggressive, and had suicidal thoughts. With little or no response to psychiatric drugs, lithium was prescribed, which culminated in hospitalization at about ten weeks from the onset of symptoms.

Working memory in this patient was impaired, along with slow thinking. No evidence of drug use was found; however, serology showed that the patient had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. In the CSF, protein levels were high; however, imaging findings were normal.

The patient was put on intravenous methylprednisolone for five days, improved rapidly, and was discharged home on both lithium and another antipsychotic. Six days later, readmission was necessary for severe anxiety, sadness, and insomnia, with the initial symptoms of aggression and suicidal ideas. This followed the substitution of the first drug with another.

While slight signs of akathisia and chorea were found, autoantibodies were absent and no new neuroimaging abnormalities were found. Protein levels in the CSF continued to be high. This time, the patient was treated with immunotherapy in the form of intravenous immunoglobulin and was ultimately discharged home on lithium with a third antipsychotic medication.

At the six-month visit, the patient showed improvement but suffered from poor memory and concentration lapses, with memory tics and anxiety. Neuroimaging was still unrevealing, while protein levels in the CSF continued to be high.

Patient 3

The third patient had no psychiatric illness prior to this admission when there was a report of altered repetitive behavior and insomnia. With a positive COVID-19 test, and no evidence of intoxication at the time, despite having a history of taking some substance a few days prior to presentation, the patient had leukocytosis, with high C-reactive protein and creatine kinase levels.

The patient experienced several psychiatric symptoms including ideomotor apraxia with loss of willpower, disorganized behavior, and agitation, while all reflexes were brisk. Following treatment with antipsychotic drugs, the CSF showed elevated proteins in three oligoclonal bands. No autoantibodies were detected and brain imaging was uneventful.

Video electroencephalography (vEEG) showed widespread beta activity. The antipsychotics were stopped and the patient returned to normal over a week, to be discharged home without the need for any medication.

Though none of these patients had signs of MIS-C, all showed CSF abnormalities. Two of the patients in this study also had intrathecal immunoglobulins that bound to mouse brain tissue, thus indicating that they are antineuronal autoantibodies and target neural tissue. These two patients also showed evidence of other autoantibodies.

While two of the patients had persistent psychiatric manifestations with poor response to antipsychotics, one responded very well to immunotherapy and the other only modestly, with continuing symptoms at six months. The third patient did not require immunotherapy and returned to normal after four days of antipsychotic treatment.

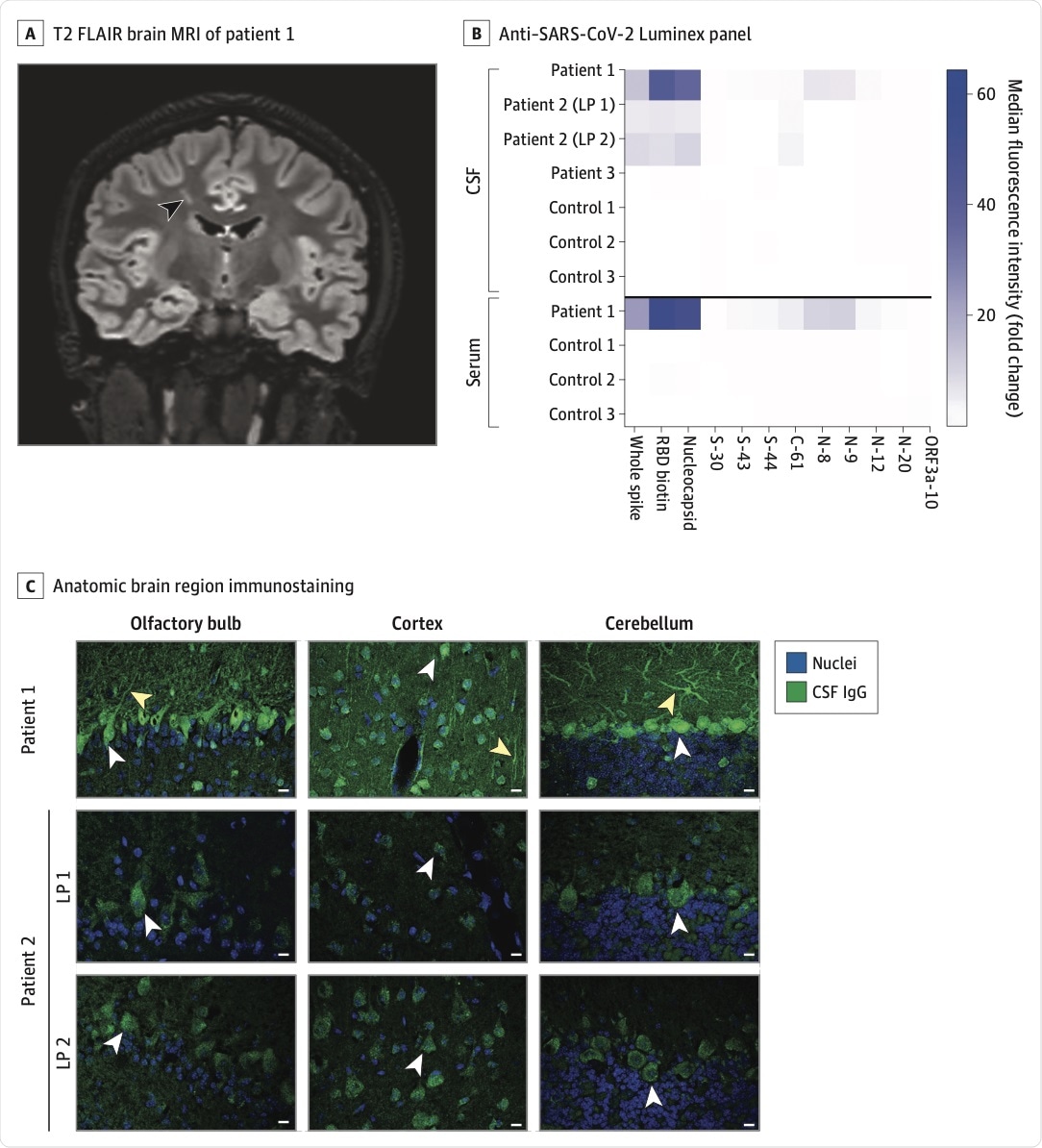

A, Coronal 3-dimensional cube T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of patient 1. A linear hyperintense lesion in the right frontal centrum semiovale is noted (arrowhead). B, Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and sera from patients and controls were screened for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies on a Luminex platform encoding whole-spike and nucleocapsid proteins, the spike receptor-binding domain (RBD), and spike, nucleocapsid, and ORF3a peptide antigens. The heatmap values represent the fold change of the median fluorescence intensity of averaged technical replicates for each biospecimen relative to negative controls. C, Select anatomic regions immunostained by patient 1’s CSF and CSF from patient 2’s first and second lumbar punctures (LPs) at a 1:4 dilution. White arrowheads in the olfactory bulb, cortex, and cerebellum indicate immunostained mitral cells, cortical neurons, and Purkinje cells, respectively. Yellow arrowheads indicate neuronal processes. Scale bars are 10 μM. IgG indicates immunoglobulin G.

A, Coronal 3-dimensional cube T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of patient 1. A linear hyperintense lesion in the right frontal centrum semiovale is noted (arrowhead). B, Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and sera from patients and controls were screened for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies on a Luminex platform encoding whole-spike and nucleocapsid proteins, the spike receptor-binding domain (RBD), and spike, nucleocapsid, and ORF3a peptide antigens. The heatmap values represent the fold change of the median fluorescence intensity of averaged technical replicates for each biospecimen relative to negative controls. C, Select anatomic regions immunostained by patient 1’s CSF and CSF from patient 2’s first and second lumbar punctures (LPs) at a 1:4 dilution. White arrowheads in the olfactory bulb, cortex, and cerebellum indicate immunostained mitral cells, cortical neurons, and Purkinje cells, respectively. Yellow arrowheads indicate neuronal processes. Scale bars are 10 μM. IgG indicates immunoglobulin G.

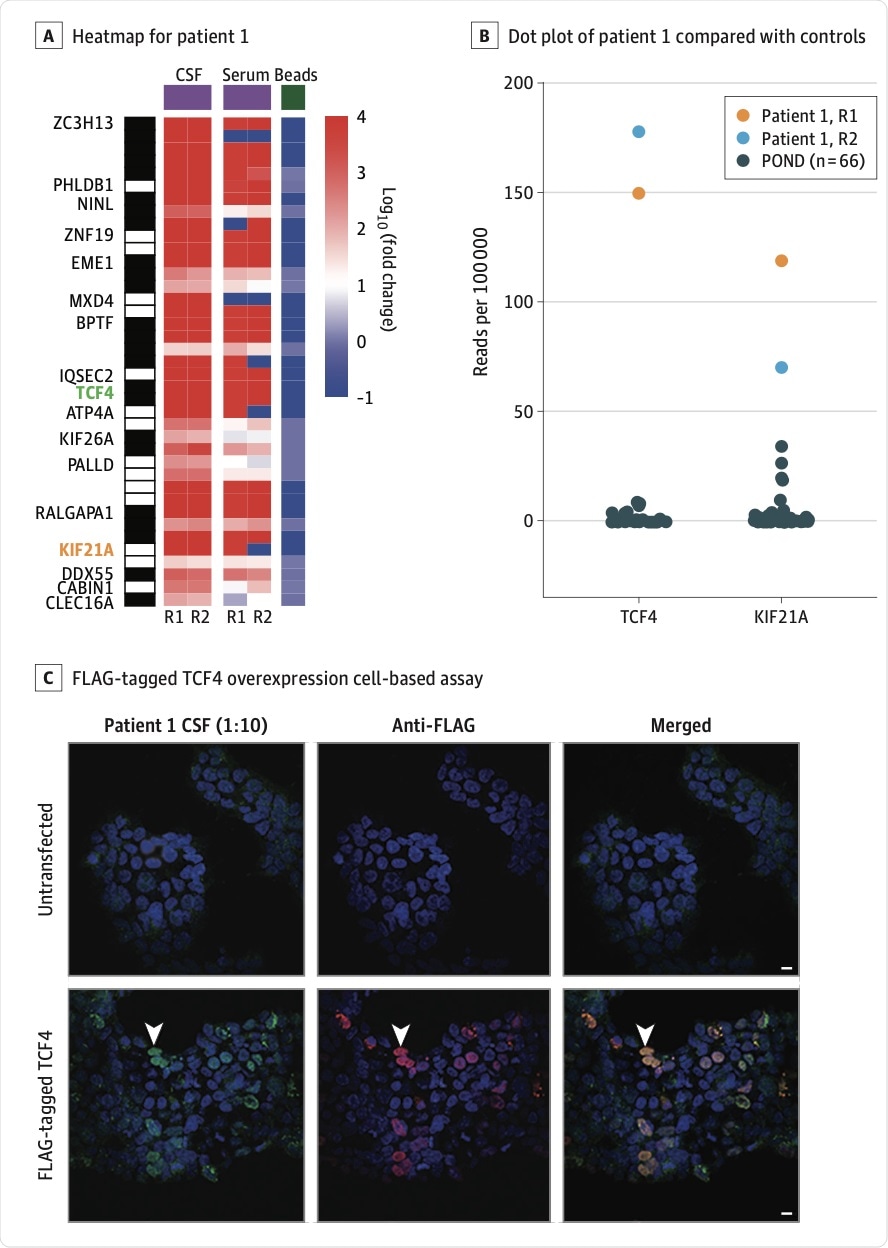

A, Heatmap of human phage display immunoprecipitation sequencing data for patient 1’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum. TCF4 and KIF21A are highlighted in green and orange, respectively. Values represent log10(fold change) relative to the mean reads per 100 000 for bead controls. The black and white barcode on the left indicates rows of individual peptides that correspond to a given protein. B, Dot plot of patient 1’s CSF TCF4 and KIF21A peptide human phage display immunoprecipitation sequencing read counts compared with CSF from 66 pediatric patients with other neurologic diseases (POND). C, HEK 293 cell overexpression cell-based assay. Untransfected cells or cells transfected with FLAG-tagged TCF4 were immunostained with CSF (1:10) and a rabbit anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were then counterstained with anti–human IgG 488 (green) and anti–rabbit IgG 594 (red). Arrowheads indicate an example of a TCF4-overexpressing cell that was immunostained by CSF IgG. Scale bars are 10 μM. R1 and R2 indicate technical replicates 1 and 2, respectively.

A, Heatmap of human phage display immunoprecipitation sequencing data for patient 1’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum. TCF4 and KIF21A are highlighted in green and orange, respectively. Values represent log10(fold change) relative to the mean reads per 100 000 for bead controls. The black and white barcode on the left indicates rows of individual peptides that correspond to a given protein. B, Dot plot of patient 1’s CSF TCF4 and KIF21A peptide human phage display immunoprecipitation sequencing read counts compared with CSF from 66 pediatric patients with other neurologic diseases (POND). C, HEK 293 cell overexpression cell-based assay. Untransfected cells or cells transfected with FLAG-tagged TCF4 were immunostained with CSF (1:10) and a rabbit anti-FLAG antibody. Cells were then counterstained with anti–human IgG 488 (green) and anti–rabbit IgG 594 (red). Arrowheads indicate an example of a TCF4-overexpressing cell that was immunostained by CSF IgG. Scale bars are 10 μM. R1 and R2 indicate technical replicates 1 and 2, respectively.

Implications

The findings of this study indicate the potential for severe neuropsychiatric illness in adolescents who contract SARS-CoV-2, even when the infection is asymptomatic or very mild. This may suggest that neuroinvasion or autoimmune phenomena are occurring in this situation in these cases.

There were few or no signs of CSF inflammation; however, CSF testing showed the presence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and neural antigens. One of the three patients showed autoantibodies to other neural antigens, such as KIF21A, which is involved in abnormal brain development as well as congenital fibrosis of the muscles of the eye.

Autoantibodies to the TCF4 gene were also detected. This is implicated in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders, as well as Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Overall, the results of this study point to the need to conduct a systematic study of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children with COVID-19 to understand the potential and mechanism of neuropsychiatric features. The role of immunotherapy also needs to be elucidated.