The impact of boosters on infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has not been fully characterized, despite existing evidence showing its efficacy in reducing the risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and death. Understanding the impact of boosters on SARS-CoV-2 infection requires analyzing the impact on mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic infections, which could be overlooked easily.

Study: Boosters protect against SARS-CoV-2 infections in young adults during an Omicron-predominant period. Image Credit: Prostock-studio / Shutterstock.com

Study: Boosters protect against SARS-CoV-2 infections in young adults during an Omicron-predominant period. Image Credit: Prostock-studio / Shutterstock.com

Background

Breakthrough infections have been common, especially following the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant, as this new strain is associated with several mutations that have increased its transmissibility. In addition to the waning of vaccine-induced antibody levels, the Omicron variant is also associated with immune evasion characteristics, which has reduced the effectiveness of United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-authorized or approved vaccines.

To prevent symptomatic and severe outcomes of COVID-19, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended a booster vaccine dose six months after completing an initial messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccination.

Limited information is available on the effectiveness of boosters with respect to the prevention of asymptomatic and mild symptomatic infections that may go unreported. Such types of infection play a crucial role in transmitting SARS-CoV-2.

Moreover, current estimates of booster effectiveness, based on the general population, might not be applicable to specific cohorts where the age distribution is significantly different from the general population.

About the study

The current cohort study was conducted in a college environment in Cornell University’s Ithaca campus between December 5, 2021, and December 31, 2021, which is when Omicron was the dominant circulating variant. A total of 15,102 university students were enrolled in the current study, all of whom were fully vaccinated with an FDA-authorized or approved vaccine including BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S.

All study participants had no record of positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test within three months of the start of the study period and were subjected to mandatory at-least-weekly surveillance PCR testing. The scientists estimated multivariate logistic regression analysis, wherein they considered participants with full vaccination with a booster dose and those without.

Study findings

Booster vaccine doses were found to significantly reduce infections in a period where Omicron was the dominantly circulating strain, which also led to minimum community transmission.

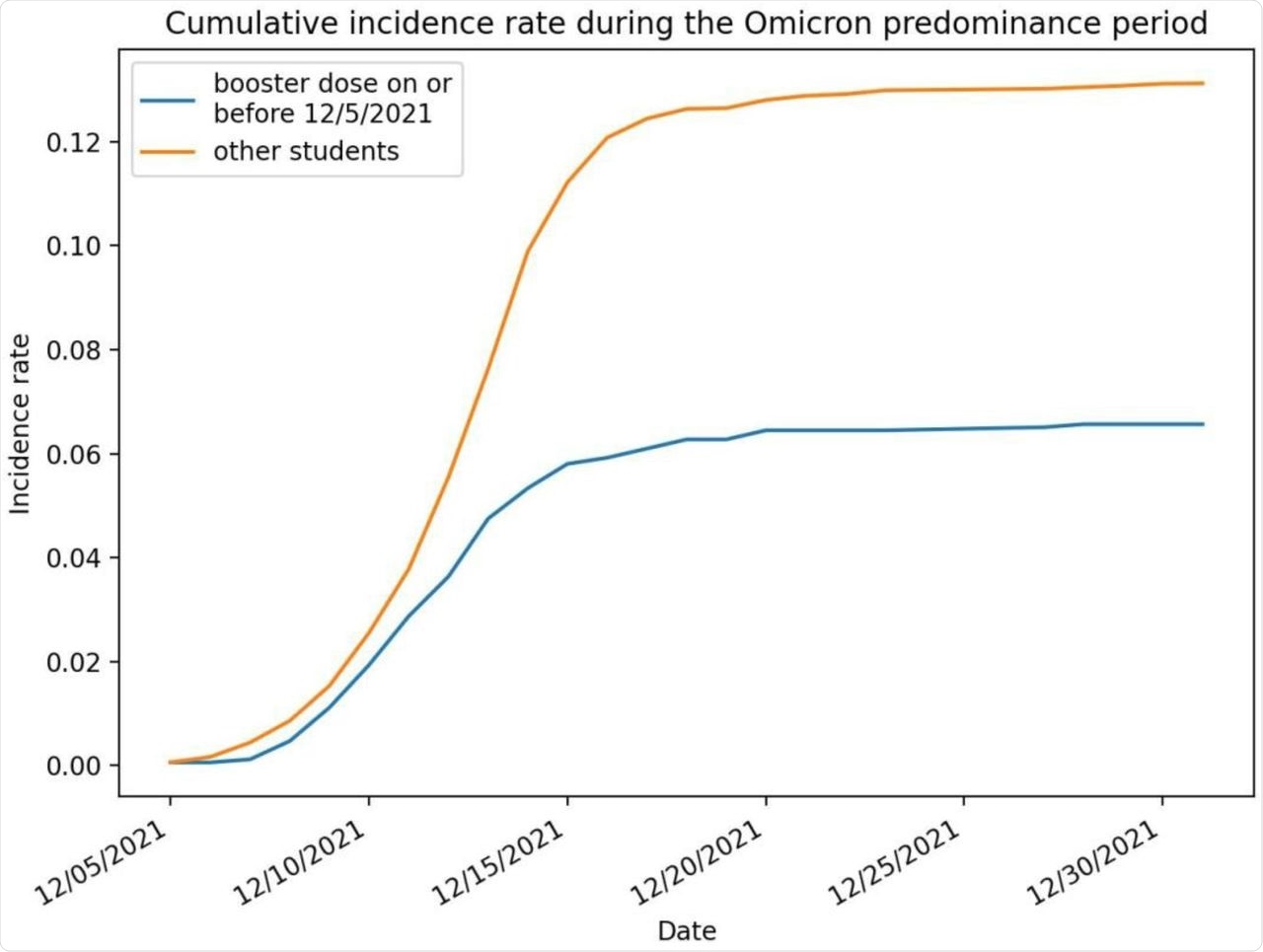

In fact, the incidence of COVID-19 was reduced by over 50% among participants vaccinated with a booster dose as compared to fully vaccinated individuals without a booster dose. More specifically, the estimated efficacy was 52%, which was reported to be lower than efficacy against symptomatic COVID-like illness in adults at 66%.

Overall, 1,870 SARS-CoV-2 infections were reported in the study population and the results controlled for various confounders, such as gender, student group membership, full vaccination date, and initial vaccine type. Importantly, the current study included both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections.

SARS-CoV-2 infection cumulative incidence rate (number of infections per person) during the study period, broken out by booster dose status.

SARS-CoV-2 infection cumulative incidence rate (number of infections per person) during the study period, broken out by booster dose status.

Students who were vaccinated with the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine were more likely to get infected as compared to those who received either of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. However, this difference was not statistically significant, perhaps because a small number of students had received Ad26.COV2.S initial doses.

The odds of infection were significantly lower among students who were fully vaccinated after May 1, 2021, and were significantly higher among undergraduate students participating in fraternity and sorority activities or athletics. Contact tracing also identified Greek-life events as significant spreading events.

Study limitations

The logistic regression assumed that the observations were independent across days, which is not consistent with modeling an individual’s behavior over time. Further, more risk-averse individuals could be more likely to enroll for a booster vaccine dose; therefore, SARS-CoV-2 exposure of boosted individuals could be different than non-boosted individuals.

Another limitation was the exclusion of students who received non-FDA-approved or authorized vaccines. The data also did not allow for distinction between booster doses and additional vaccination for immunocompromised individuals.

The researchers mentioned that 100% sequencing of positive PCR tests was not done; thus, misclassification could not be ruled out, as individuals boosted during the study period may have uploaded their vaccination records. Lastly, information on previous SARS-CoV-2 infections was not available, and the sample size was not large enough to estimate how booster effectiveness varied across manufacturers of the booster dose or the original vaccine.

Conclusions

Booster vaccine doses are effective in reducing SARS-CoV-2 infections in young adults as compared to full vaccination without the booster dose in a period of Omicron variant predominance. The implication of these results is that the booster vaccination rate should be increased so that educational institutions could safely remain open while also reducing community transmission.

Important notice*

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.