Phthalates are essential elements in the plastics sector and, as a result, are often found as contaminants throughout the surrounding environment. Within the environment, phthalates can disrupt endocrinal functions by being readily absorbed by humans and binding with molecules that interfere with the hormonal imbalance. Thus, phthalate exposure can lead to a variety of diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), across ages.

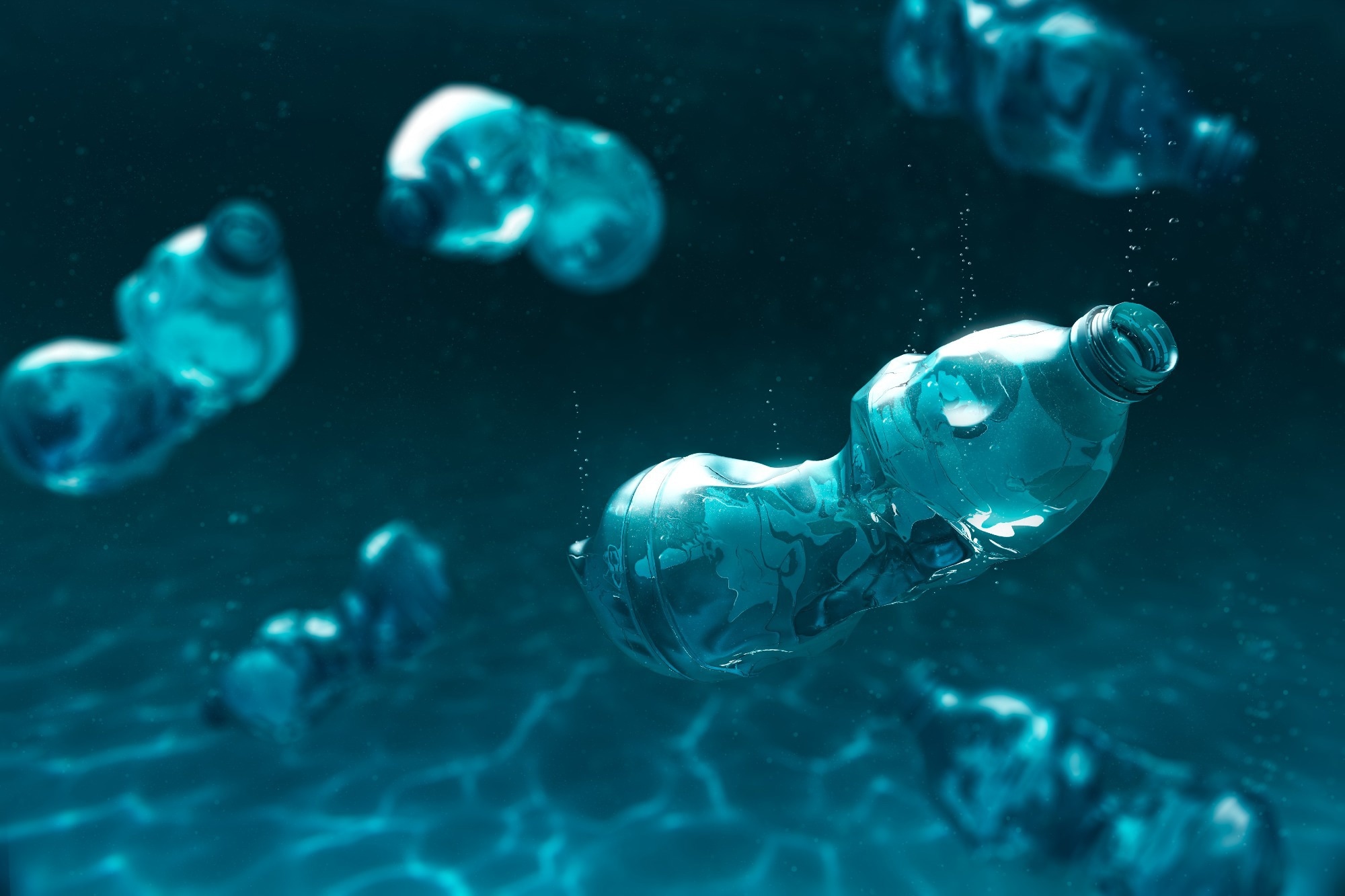

Study: Phthalates’ exposure leads to an increasing concern on cardiovascular health. Image Credit: Fer Gregory / Shutterstock.com

Study: Phthalates’ exposure leads to an increasing concern on cardiovascular health. Image Credit: Fer Gregory / Shutterstock.com

About the review

Databases such as the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed were searched for relevant records published between 2015 and April 2022. Only human experimental or epidemiological studies that included males and females and assessed the impact of phthalate exposure on CVD risks among individuals of all ages were included. Non-human studies, duplicate records, inaccessible records, and studies published in non-English languages were excluded.

What are phthalates?

Phthalates are chemicals categorized by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as priority environmental polluting substances.

High-molecular weight phthalates are used to improve the elasticity and flexibility of polymers such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) in various industrial and household products, such as furniture, tiles, adhesives, paints, rainwear, shower curtains, automobile upholstery, footwear, dust, food packaging, medical devices, diapers, and toys. Low-molecular-weight phthalates are used as additives and solvents in paints, sinks, and personal care products, such as cosmetics.

Phthalates are capable of leaching into the environment, as they do not bind covalently to polymers. Phthalates have been identified in water, air, food, consumer products, and biological fluids such as blood, urine, amniotic fluid, saliva, and human milk.

Inhalation, ingestion, and absorption through the skin are the primary exposure routes. However, prenatal and intravenous exposure during medical interventions is also concerning.

Effects of phthalate exposure on cardiovascular health

Exposure to certain phthalates, including monomethyl phthalate (MMP) and monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP), may promote atherosclerosis by facilitating carotid artery plaque formation and altering carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT).

Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) exposure promotes endothelial cell apoptosis, alters deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) methylation, and facilitates atherosclerosis due to pro-atherogenic and pro-senescence activities, with cholesterol efflux inhibition through altered microRNA 200 c (miR200c)-5p-ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1 (ABCA1) activity. DEHP also upregulates plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 expression and has procoagulant effects.

Phthalates like DEHP and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) metabolites, including mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP), monobutyl phthalate (MBP), and mono-isobutyl phthalate (MiBP) can increase the levels of atherothrombotic markers such as fibrinogen, plasma D-dimer, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein among coronary artery disease (CAD) patients.

Phthalates like MEP alter blood pressure by potentiating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) activity and inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Interestingly, maternal exposure to phthalates reduces blood pressure (BP) in the offspring, whereas direct exposure to phthalates among children increases BP. In addition, MEP exposure increases the risk of pre-eclampsia due to enhanced soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor ratios (sFlt-1/PlGF), increased oxidative stress, and inflammatory cytokine production.

DEHP alters cardiac electrical conduction by decreasing the expression of genes associated with cardiac cell electrical activity and calcium transport, including connexin 43, calponin, and calsequestrin, and reducing calcium levels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Phthalate exposure, especially DEHP, may lead to impaired recovery among patients who undergo cardiac surgeries due to decreased cell viability and mitochondrial membrane potential, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, promoting apoptosis in cardiomyocytes.

Exposure to certain phthalate, especially MBP, may lead to stroke due to glycolytic pathway disruptions and inhibition of proteins associated with DNA transcription and ribonucleic acid (RNA) biogenesis. In addition, phthalates increase cardiometabolic risks such as diabetes by increasing gestational weight gain, impairing glucose tolerance, increasing insulin resistance, and altering pyrimidine, amino acid, and galactose metabolism.

Phthalate exposure may also cause obesity due to increased triglyceride and total cholesterol levels. In addition, phthalates disrupt hormonal balance due to their anti-androgenic, estrogenic, and anti-thyroid effects.

Conclusions

Based on the review findings, CVDs may develop among individuals of all ages and sexes who are frequently exposed to phthalates.

Phthalate consumption could be reduced by minimizing the intake of canned and packaged foods and using stainless steel, porcelain, glass, or eco-friendly ‘green’ products instead of plastic ones. The general public must also be educated on the harmful effects of phthalates and their presence in various daily-use products and the environment.

Journal reference:

- Mariana, M., Miguel Castelo-Branco, M., Soares A. M., & and Cairrao, E. (2023). Phthalates’ exposure leads to an increasing concern on cardiovascular health. Journal of Hazardous Materials. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131680