Even as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to take hundreds of thousands of lives and affect the health of nearly 5 million people in 188 countries and territories around the world, its clinical course, pathogenesis, and treatment continue to be debated by scientists around the world. So far, case fatality rates (CFRs) have been shown to vary widely from country to country.

Why is mortality due to COVID-19 so different across countries?

Some reasons for the difference in death rates could be the variation in age profile, the extent of community spread, the capacity and level of preparedness of the healthcare system, and the prevalence of other comorbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Low testing levels also cause a falsely elevated case fatality rate (CFR) as the asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic cases go mostly unreported and undiagnosed.

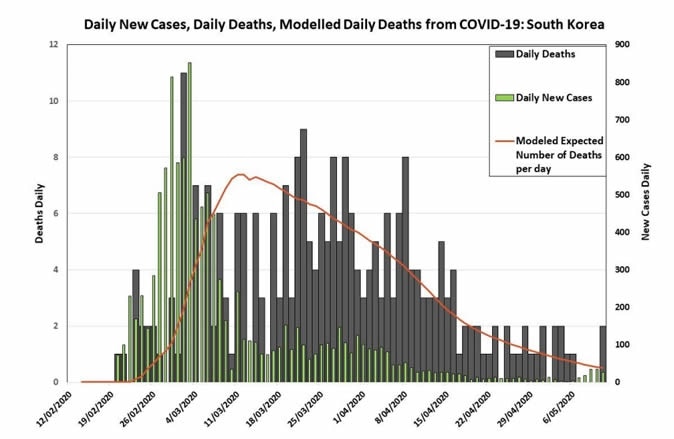

The timing of a fatality rate study is also important in determining the reported case fatality. If the outbreak started early, as in South Korea, the number of cases that have reached an outcome will be significant in comparison to unresolved cases, ensuring a more accurate CFR.

Why Australia vs. South Korea was chosen

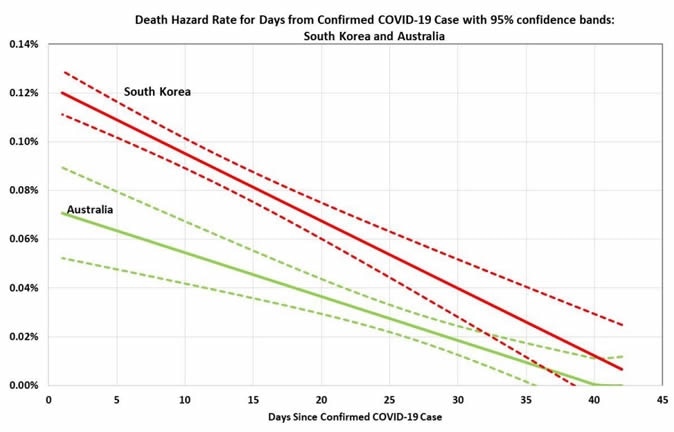

The current study by two Australian researchers at Monarch Institute, Melbourne, and Canberra Hospital set out to estimate the daily hazard rate for death from the time of case confirmation to case resolution. It included data from South Korea and Australia in its analysis. The reasons for choosing these countries include their widespread testing and contact tracing programs, and the relatively low stress caused by the disease on healthcare systems.

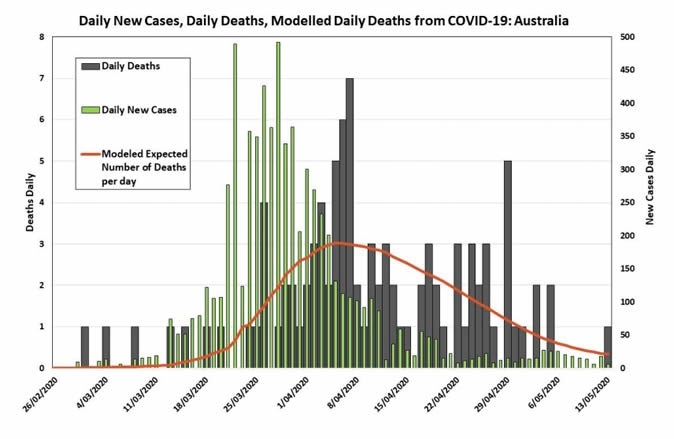

The number of new cases has dropped to small numbers at present. The crude mortality rates due to COVID-19 are 2.4% and 1.4%, respectively. Together, the data indicate that the first wave is almost complete in both countries.

The importance of the hazard rate estimate for death is its utility in finding the estimated terminal CFR, which is the same as the case fatality rate in hindsight if the disease should be extirpated. It will also assist in arriving at the right case fatality rate instead of the reported one, which necessarily leaves out the currently active cases whose outcome is as yet unknown.

How was the study done?

The study was based on the daily confirmed case and death count from the Australian Government Department of Health website and the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. The study period covered the duration between January 22 to May 12, 2020.

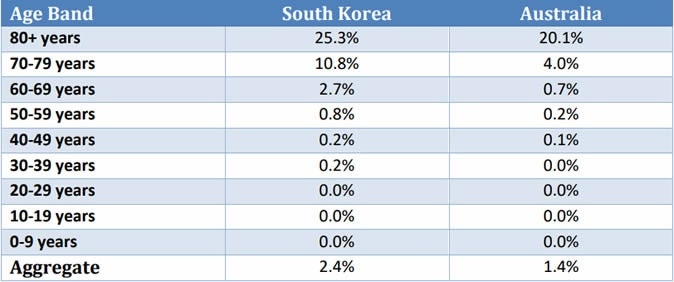

The researchers found that the same pattern was present in both South Korea and Australia when the death counts are stratified by age group. In general, older people show higher mortality rates, while younger cohorts have very low mortality. Age-specific fatality rates are higher across the age spectrum in South Korea, as is total fatality.

The researchers conclude that daily death hazard rates will also be higher in South Korea than in Australia. When they applied the age-specific CFRs from South Korea to the age-stratified Australian case count, they arrived at a prediction of 265 deaths. The aggregate CFR for Australia, in this case, is 2.6%.

Significantly different CFRs in Australia and South Korea

This is slightly higher than the 2.4% CFR of South Korea, due to the increased proportion of older people in the COVID-19 patient subset in Australia compared to South Korea. On the other hand, the predicted CFR is almost twice the actual Australian CFR, which was 1.4% as of May 9, 2020.

The terminal CFR for Australia is 1.4%, significantly less than the South Korean 2.4%. This shows that the difference in the aggregate reported CFR between the two is not explicable in terms of the different timeline of the epidemic in both countries.

The reasons for such a difference are not clear, since both have excellent health systems, and the epidemic in both countries was rapidly contained, without significantly overstraining the hospital systems.

It is seen that, like other places, the initial CFRs in Australia were much higher initially, for a couple of weeks, compared to later on, probably due to the lower rate of testing at that time, but also because many older people were infected while traveling abroad, as in cruise ships, at the time of the earliest outbreak.

Case Fatality Rates by Age Band

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Seasonal variations

The seasons in the two countries were also different, Australia experiencing late summer and autumn but Korea being in winter. Winter may be conducive to viral spread, with easier transmission and a more complicated course following lung involvement. This is similar to the differences in CFR due to the Spanish flu a hundred years earlier, where secondary infections, as well as immunity to bacteria and viruses, were responsible for a large part of this variation.

Strain variations

Minor mutations may also have resulted in strain variations between the different countries in their respective COVID-19 outbreaks. In addition, it is possible that older Koreans may have been additionally vulnerable due to nutritional and other health impacts of the Korean War that occurred when those in their seventies and eighties were just children.

Protocol variations

Another reason could be that the standard of hospital treatment in either country follows different protocols, including significant variations in ICU care, which could have significantly changed the outcome. If so, these should be identified. Antibiotic resistance for many bacteria is also present at higher rates in Korea compared to Australia, which could be important if secondary bacterial infection is a significant cause of death in COVID-19.

Pathogenicity Variations

Most of the Australian cases came from people returning from outside, especially from Europe and the US, and from cruise ships, rather than from community spread. In Korea, too, most imported cases came from the Western hemisphere. Still, a crucial difference could be that the initial phase of the epidemic followed by local clusters of infection came from people infected in China. This could signal a change in viral pathogenicity over time, contributing to different CFRs.

Long fatality trails

The analysis also indicates a lag between case confirmation and death by about 2 weeks in both countries, but a significantly long tailing of mortality, in some cases the death occurring even a month after the confirmation of the case. This could indicate that if the health system can cope, the patient is likely to be in the ICU for much longer than with an overwhelming patient load. This may lead to shorter tails for epidemics in places like Italy and New York, where the outbreaks were shorter and far more intense.

The study concludes, “It will be important to better explore difference in the virus strains, variations in carriage of bacteria (e.g., pneumococcus) and/or how healthcare is delivered to try and unravel what are the most important factors that may have contributed to this difference.”

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.