The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has already taken over 2.8 million lives worldwide while still continuing to cause tens of thousands of new cases every day. Many of these are pregnant women.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Pregnancy increases risk?

Some earlier reports suggest that pregnant women are more likely to develop severe COVID-19, with a higher risk of being admitted to the intensive care unit, being put on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and death.

Among this population, Hispanics appear to be at higher risk of infection, but Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks may have a higher risk of disease progression. However, the transplacental spread of the virus to the fetus is extremely rare, and outcomes such as miscarriage or stillbirth are also not more frequent in this group, though preterm delivery may be more common.

Vaccination in pregnancy

Several vaccines have been rolled. These include the Oxford Astra-Zeneca vaccine, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, and the Moderna vaccine.

Pregnant women were excluded from the clinical trials. Nonetheless, professional societies recommend that this decision be reversed and that vaccines be offered in pregnancy as well. This is also the stance of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The current study aimed to explore how willing pregnant women were to get vaccinated, operating on the hypothesis that women from minority groups would show vaccine hesitancy or unwillingness to a greater extent than those in the mainstream.

Study details

The data came from the Epidemiology of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 106 Pregnancy and Infancy (ESPI) Community Cohort, a prospective longitudinal cohort study meant to provide incidence, risk factors, and range of clinical manifestations among pregnant women.

Women were excluded if they had no working telephone or could not read and speak English or Spanish and if they could not commit to weekly evaluation.

The study eventually included 915 women, with 40%, 25%, and 33% being White, Black and Hispanic, respectively. Almost two-thirds had received an education past high school, and 60% had a job. Only a fifth lived below the poverty line, while about 30% had one or more comorbidities.

What were the results?

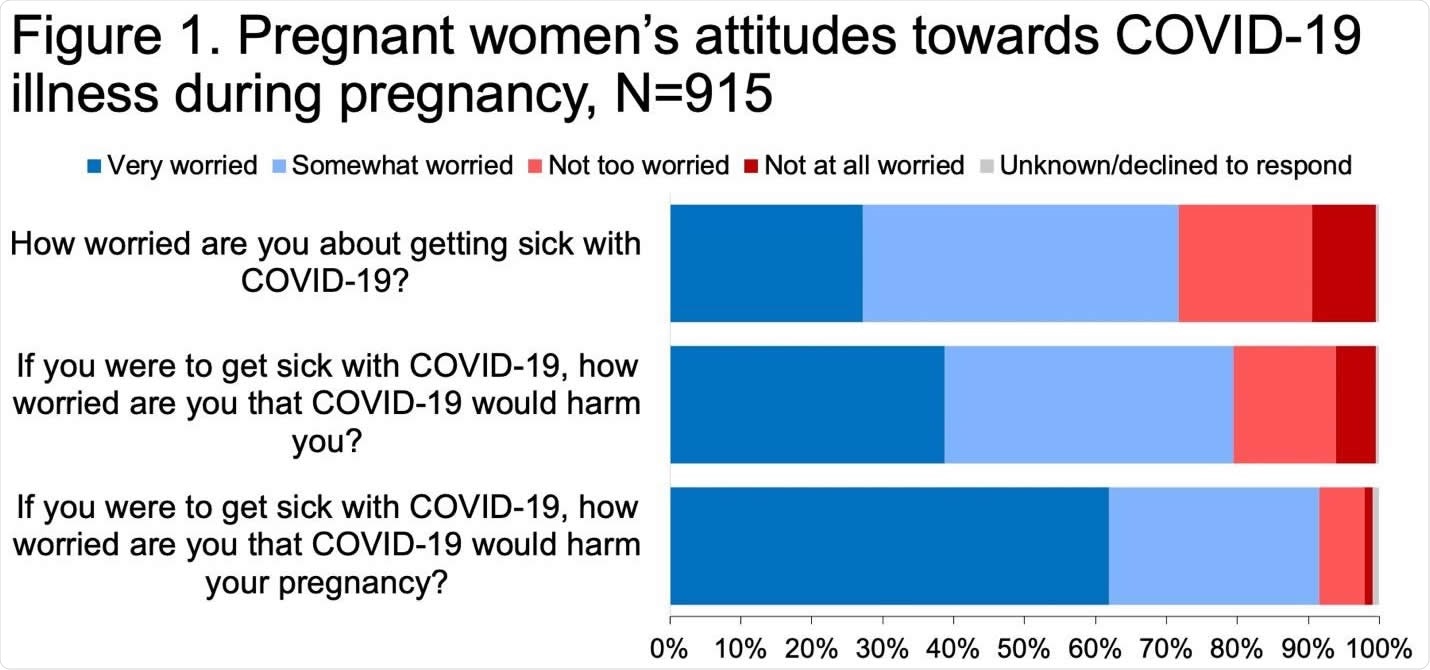

About 72% said they worried about falling ill with COVID-19, while over 90% said they worried that it would have an adverse impact on the fetus. Personal harm was feared by 80%.

About 40% said they relied chiefly on their doctor to get reliable information, while some cited the CDC or other medical workers.

Again, about the same number said they would accept a vaccine once available, even during pregnancy. Their reasons for being open included the desire to protect the fetus from harm, protect the family or the community.

Vaccine hesitancy was associated with fear of severe adverse reactions and doubts about the utility of efficacy of the vaccine.

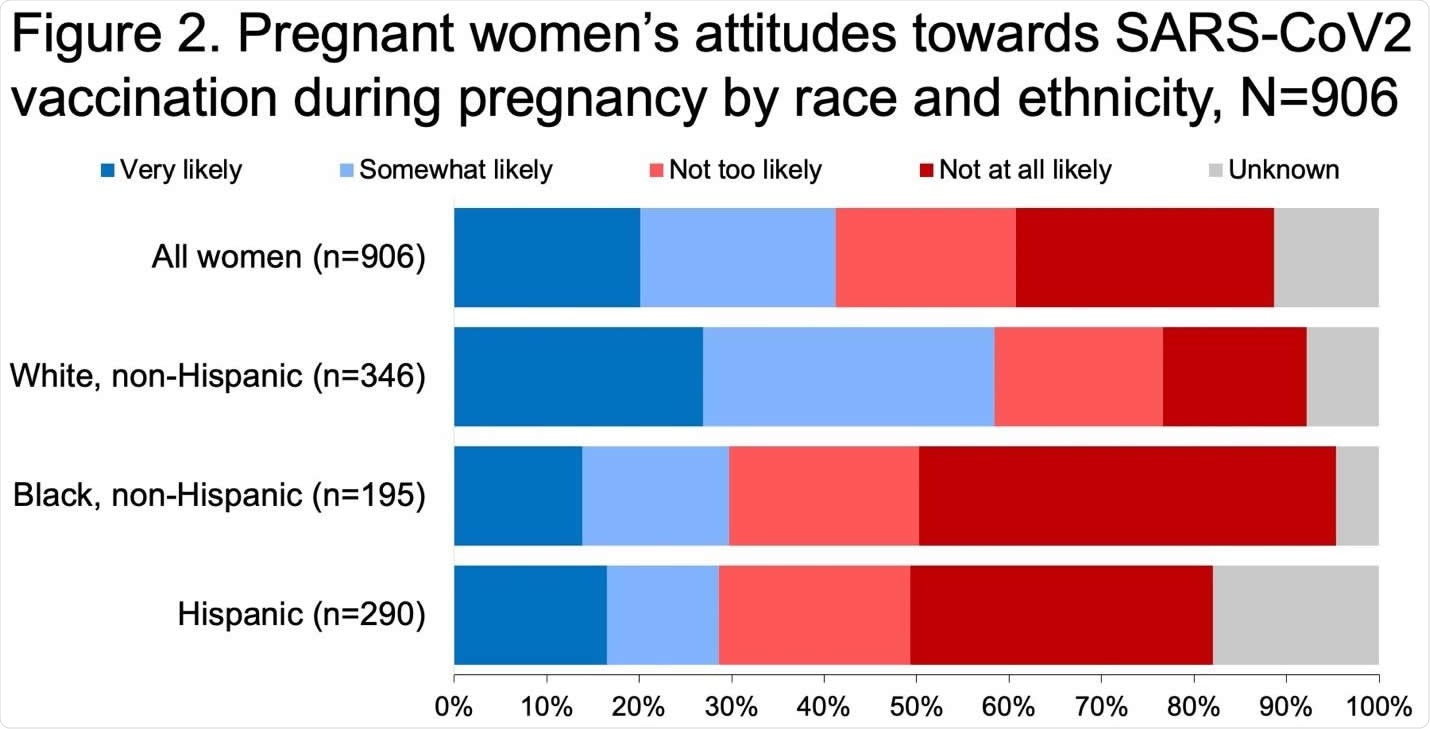

Willingness is multifactorial and depends in part on race and ethnic origin. White women seemed more willing to get the vaccine, at 63%, vs. 30% and 35% of non-Hispanic Black and Hispanics, respectively. The latter were 60% less likely to accept the vaccine.

The only other correlations were with a history of having taken flu shots in 2019-20 – such women were more than twice as likely to be willing to take the vaccine. Again, women who were apprehensive about coming down with the illness were somewhat more likely to be willing to get vaccinated.

What are the implications?

While almost 75% of pregnant women expressed worry about the infection for themselves and their babies, less than half were willing to get vaccinated once shots became available. This trend of vaccine unwillingness was stronger among racial and ethnic minorities.

Conversely, a history of influenza shots in the previous flu season predicted a higher chance of being willing to take the vaccine. Safety concerns were paramount among the concerns that hindered vaccine acceptability, often coupled with doubts about vaccine efficacy.

These issues have been encountered with previous studies of flu shots in pregnancy.

Encouragingly, most women in the current study cited their doctors as their most common sources of information about the illness. Physician recommendations have been among the best predictors for flu vaccination worldwide.

“Our findings indicate that obstetricians and other healthcare providers will play a critical role in counseling pregnant women about the risks of COVID-19 illness and providing information about the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.”

Currently, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine (SMFM) recommend offering pregnant women COVID-19 vaccines, with both physician and patient sharing the decision on taking it.

A long history of the unscrupulous use of minorities for medical research has led to a suspicion of modern medicine among them. In addition, there are gross inequities in social and health development affecting these groups. These may account for their lower willingness to take the vaccine.

Recently, it has been found that Black women had a lower chance of being offered shots for the flu, or Tdap vaccination and that vaccination rates for both during pregnancy were lower among this community.

COVID-19 rates are also higher among these minority groups, particularly among pregnant women from these communities. While non-Hispanic Black or African American women make up only 15% of pregnant women with COVID-19, they comprise 27% of pregnancy deaths due to this illness.

Infection rates were also higher among Hispanic women during pregnancy compared to non-pregnant Hispanic women. Thus, these minorities are at particular risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 but are less likely to accept the vaccine.

This should “highlight the need for outreach and communication strategies to address perceived barriers to vaccination among groups that may be less likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine.”

Such an approach should probably take advantage of the trust enjoyed by healthcare providers to allow them to play a more significant role in recommending the vaccine.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Battarbee, A. N. et al. (2021). Attitudes toward COVID-19 illness and COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women: a cross-1 sectional multicenter study during August-December 2020. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.26.21254402. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.26.21254402v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Battarbee, Ashley N., Melissa S. Stockwell, Michael Varner, Gabriella Newes-Adeyi, Michael Daugherty, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, Alan T. Tita, et al. 2021. “Attitudes toward COVID-19 Illness and COVID-19 Vaccination among Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study during August-December 2020.” American Journal of Perinatology, October. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1735878. https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0041-1735878.