Studies have demonstrated that several species are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly pet cats and dogs residing close to humans. They are the most exposed; however, under experimental conditions, they are infected only transiently, showing mild symptoms.

In the Netherlands, captive minks contracted a viral infection from humans, which they retransmitted to humans and cats, and dogs. In rare cases, animals have died post contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection; however, defining the contribution of SARS-CoV-2 to death is challenging.

Although most viral infections in pets originate from human owners, risk factors for such zoonotic transmission and the nature and frequency of their clinical illness are not well defined.

About the study

In the present study, researchers investigated SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity in household pets and animals in shelters and neuter clinics in Ontario, Canada. Additionally, they used univariable analysis to analyze household risk factors related to SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity.

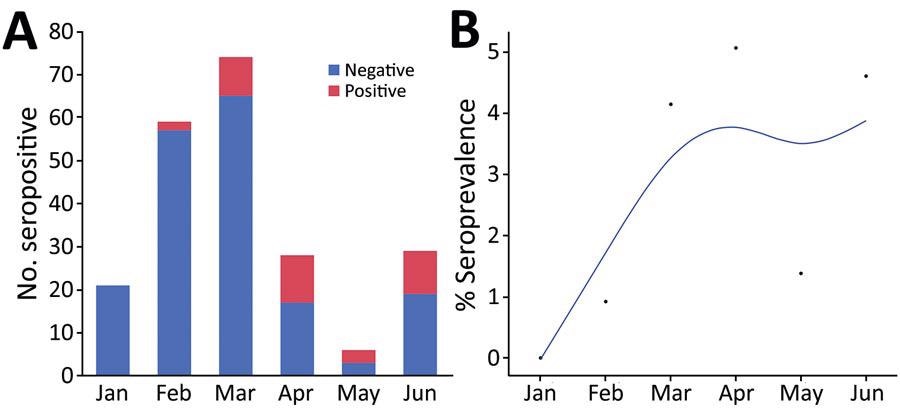

Seropositivity for SARS-CoV-2 in cats brought for care to a low-cost spay/neuter clinic during January – June 2021, Ontario, Canada. A) Test results for 221 cats shown by month. B) Positivity rate per month. The points indicate the proportion of positive test results among all test results over time. Blue line indicates the smoothed rate of seropositivity. The association between month and the change in seropositivity was significant (p<0.0001).

The study veterinarians invited pet owners diagnosed with COVID-19 (in the previous three weeks) to bring in their pet dogs, cats, and ferrets for swab sample collection between April 2020 and August 2021. They collected swab samples from animals’ distal nares, oropharynx, and rectum. The median age of dogs and cats was five and six years, respectively.

The team first performed a quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) on the collected swab samples. Further, they performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on the samples testing positive for the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N1) gene.

Between June 8, 2020, and November 30, 2021, they collected blood samples of pet animals from owners with SARS-CoV-2 infection two weeks to three months previously. They analyzed these samples using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM against SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein.

They performed the surrogate virus neutralization test (sVNT) on the first 42 serum samples and the remaining 70 samples with IgG optical density (OD) greater than 1.4. The sVNT test determines whether the interaction of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is blocked.

Lastly, the researchers asked pet owners to complete an online survey for information regarding household demographics, their interaction with pets, and any new illnesses in them.

Study findings

There were 283 swab samples from pet cats, dogs, and ferrets. The samples of six animals tested positive in RT-qPCR with N1 PCR cycle threshold (CT) values <35.99. WGS-sequenced samples from two RT-PCR-positive cats were assigned lineage B.1.2 and A.23.1 during phylogenetic analysis. The sequences were similar to human SARS-CoV-2 sequences from the same geographic region.

The IgG and IgM seropositivity was 25–48% at a standard deviation (SD) greater than six, above the mean cutoff for the negative control. While at greater than six SD, all IgM positive dogs were IgG positive, 25% of cats were IgG positive but IgM negative.

For dogs, the researchers observed a statistically significant correlation between seropositivity and the onset of the new respiratory infection at the time owner contracted COVID-19. However, they did not observe an association between time spent every day with the SARS-CoV-2-infected owner for both dogs and cats. Likewise, there was no effect of multiple pets or more than one confirmed COVID-19-positive case in the household.

Sleeping in the owner’s bed was a risk factor for seropositivity in cats with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.8, as indicated by a univariable risk analysis. However, it was not the case with dogs. Of the 53 samples analyzed via sVNT, 76% of samples positive on sVNT were also positive for IgG and IgM at six SD. Upon repeating risk factor analysis using the samples tested by sVNT, the authors noted that licking the hands or face of owners was associated with seropositivity for dogs, with OR=10.5.

The authors also noted a significant correlation between the ELISA OD and the neutralization of virus binding. Notably, the correlation between ELISA and sVNT results was higher for cats than dogs.

Conclusions

Although the study data confirmed the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected humans to their pets, PCR-based detection indicated the brevity and transient nature of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pets, as observed in experiments with cats. The observed seropositivity was much higher than PCR positivity in pet animals. It is noteworthy that serologic data represent historical exposure and does not require sampling during the narrow infection window. Accordingly, a relatively high proportion of dogs and cats had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 S protein, indicating infection or exposure. Moreover, the svNT results correlated with the ELISA results. Despite small sample sizes, risk factor analyses identified correlations linked to the duration and closeness of human-animal contact.

Cat-to-cat SARS-CoV-2 transmission has been identified. Therefore, the zoonotic risk posed by cats is probably higher, but the actual risk for a cat-to-human transmission is unknown. Nevertheless, confirmed human to dog and human to cat transmission highlight the need for further study to understand the animal and human health consequences of spillback of SARS-CoV-2 into pet animals.

Journal reference:

- Dorothee Bienzle, Joyce Rousseau, David Marom, Jennifer MacNicol, Linda Jacobson, Stephanie Sparling, Natalie Prystajecky, Erin Fraser, and J. Scott Weese, Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection and illness in cats and dogs, Emerging Infectious Diseases 2022, DOI: 10.3201/eid2806.220423, https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/28/6/22-0423_article