A new study has shown that the immune cells within the gut could be related to the rate of metabolism. The results of the new study titled, “Gut intraepithelial T cells calibrate metabolism and accelerate cardiovascular disease,” are published in the latest issue of the journal Nature.

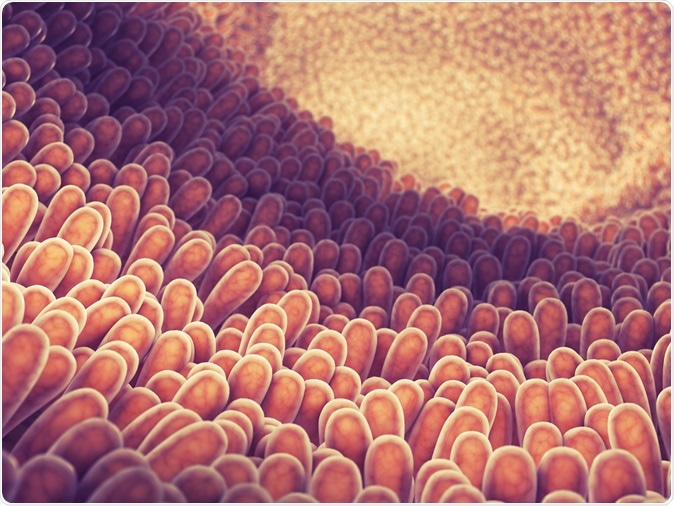

Intestine lining and villi illustration. Image Credit: nobeastsofierce / Shutterstock

The researchers led by Shun He, used genetically engineered mice for their study. They noted that when certain immune cells are present in the body, they tend to slow down the metabolism and the ingested nutrients are all converted and stored as fat within the body. On the other hand lack of these immune cells help convert the nutrients into energy. The team used engineered mice which specifically lack these immune cells and found that this made them consume diets rich in sugars, fats and salts but did not predispose them to develop hypertension, obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

This study could mean that removing these immune cells from the gut could alter the metabolism. Some individuals who are genetically predisposed to having these immune cells thus have slow metabolism and are so called “thrifty” because they store the nutrients as fat instead of burning them off as energy. Study co-author Filip Swirski, Associate professor at the Harvard Medical School and a principle investigator at the Center for Systems Biology at the Massachusetts General Hospital explained, “When you eat a meal, your body needs to decide what to do with the energy in the meal. The immune cells calibrate that decision and essentially they put the brakes on a high metabolism.”

The team first began their study looking at a protein called integrin beta7. This protein basically directs the immune cells towards the gut. They noted that mice that were engineered to lack the gene coding for this protein ate a lot but did not become obese. Activity levels of these engineered mice were no different from normal mice. Swirski said, “They just run hot... They have a higher basal temperature.”

The team took two groups of mice – one group engineered and one group normal. Both were offered high fat diet that was also high on sugar and salt or sodium. This type of diet normally causes metabolic syndrome with obesity, diabetes, high blood cholesterol, high blood pressure and heart disease. They noted that the mice that did not have the integrin beta 7 protein did not become obese and did not develop diabetes or hypertension. All these features were seen in the non-engineered mice group. The mice that did not have the protein also did not develop coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis.

Next they looked at the reason behind this difference. They noted the T cells in the small intestines seem to be different between groups. Swirski explained, “This is where we stumbled on GLP-1.” He explained that this is a metabolism-stimulating protein. They noted that the T cells or intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) from the gut had large number of GLP-1 receptors. They found that the mice that had more beta7 protein and less or absent GLP-1 receptors seemed to have faster metabolisms. Swirski explained that this proved that “crucial cells were T cells that express the GLP-1 receptor.”

Swirski explained that the main reason behind these systems of slowing metabolism was the human evolution over periods of food shortages. He said, “Having this kind of brakes under those conditions would be advantageous to survival... It would mean you could store ingested food for longer since it was converted to fat to be used if you didn’t have frequent meals.” He added that this mechanism now has turned problematic because of the over-abundance of food.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health.