A new study in rats published in the journal Cell Reports shows that the pattern of RNA molecules produced within certain immune cells called macrophages, found within breast cancers (tumor-associated macrophages, TAMs), can tell whether the tumor is cancerous or not and indicate the type of outcome. The same pattern is present in humans as in mice. This makes it directly useful in predicting the nature of a breast tumor and its outcome.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in US women. There are multiple types of breast cancer, but most show up initially as a lump, change in breast size or shape, skin changes over the breast, or recent nipple changes. Most often breast cancers begin in the duct cells, but also in the gland lobules or other breast tissues. About 5% to 10% of breast cancers are due to gene mutations, especially BRCA1 and BRCA2. Breast cancer screening can help catch these tumors early, offering an excellent chance of curative therapy.

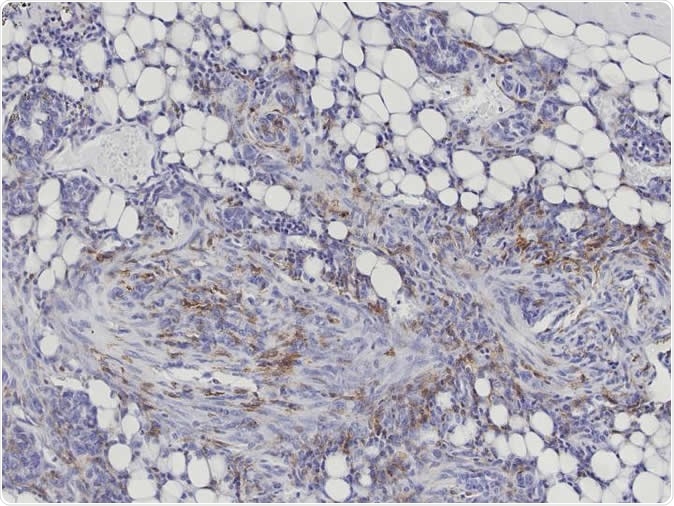

Macrophages (brown), the scavengers of the immune system, migrate into the diseased tissue (cancer cells: blue) without destroying it. Image Credit: Karin E. de Visser/the Netherlands Cancer Institute

Tumors and the immune response

Tumors growing in the body typically induce an immune response since they carry some different cell surface molecules compared to normal cells. The first defenses include macrophages, which non-selectively engulf and kill the identified cancer cell, digesting them once they have been completely ‘eaten’ by the macrophage. These scavenger (TAMs) are typically found in large numbers within cancers.

Some clever tumor cells, however, manage to fool the troops and escape, to then turn the macrophages themselves to their own use. The resulting cooperative environment enhances the growth of the tumor from these cells.

Such aggressive cancers are capable of changing the immune response to favor themselves, by encouraging the production of some cell signaling molecules and inhibiting others. In order to suppress or promote the expression of any gene product, tumor cells signal the DNA of the genome – causing a corresponding change in the RNA signature.

The study

The study compared TAM transcriptomes with those of macrophages from healthy tissue. First the researchers studied the normal macrophages from different body sites, and identified a variety of ‘normal’ RNA patterns or transcriptomes, depending on which organ the macrophages are found in. This influence is called ‘tissue painting’, in that the tissue in which the macrophages operate leaves an imprint on the immune cells. It is important to compare TAMs from a cancer to the healthy macrophages from the same type of healthy tissue, to avoid transcriptional changes due to organ-specific imprinting.

They also identified the tumor-induced changes in the transcriptome of different TAMs, which can vary significantly from patient to patient, depending on which mutation is responsible for the tumor.

The findings: first in mice…

To put all this together, the scientists used mouse cell lines in which specific well-delineated types of breast cancer have been induced – namely, those which are look-alikes for human invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) and HER2+tumors, respectively. They learned which changes can be expected in TAMs from each type of mouse tumor compared to macrophages from healthy breast tissue, using cutting-edge computational techniques.

The researchers found that both TAM types showed unique transcriptomes due to the effect of the tumor on the macrophage’s transcriptional signaling. They were not only different from macrophages derived from healthy breast tissue but also from each other, which means the tumor subtype decides which genes will be switched on and off for each type of breast cancer.

And then in women…

The shocker came when they compared these signatures with those found in the TAMs of many patients with breast cancer. They were virtually identical, when TAMs from one type of mouse breast cancer were compared to those from the same type of tumor in humans. Says researcher Joachim Schultze, “In this case, it was possible to transfer the mouse results directly to humans.”

Implications

In the current study, the scientists found that they could predict the nature of the tumor in humans depending on their observations in mice, provided they used the right models. And more, they found that these changes also showed them some of the tricks used by the cancer cells to bypass normal immune mechanisms. Knowing this could be very helpful in eventually developing new treatment options, though this may take decades.

Journal reference:

Transcriptional signature derived from murine tumor-associated macrophages correlates with poor outcome in breast cancer patients. Sander Tuit,Camilla Salvagno, Theodore S. Kapellos, Cheei-Sing Hau, Lea Seep, Marie Oestreich, Kathrin Klee, Karin E. de Visser, Thomas Ulas, and Joachim L. Schultz. Cell Reports. 29, 1221–1235October 29, 2019. https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)31264-1