The team says poor wastewater management can lead to these species being exposed to the virus, which could have devastating effects on marine mammal populations that are already on the decline.

Graham Dellaire and colleagues also discuss potential approaches to reducing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 spilling over into rivers and ocean so that further damage to these already vulnerable marine populations can be prevented.

A preprint version of the paper is available on the server bioRxiv*, while the article undergoes peer review.

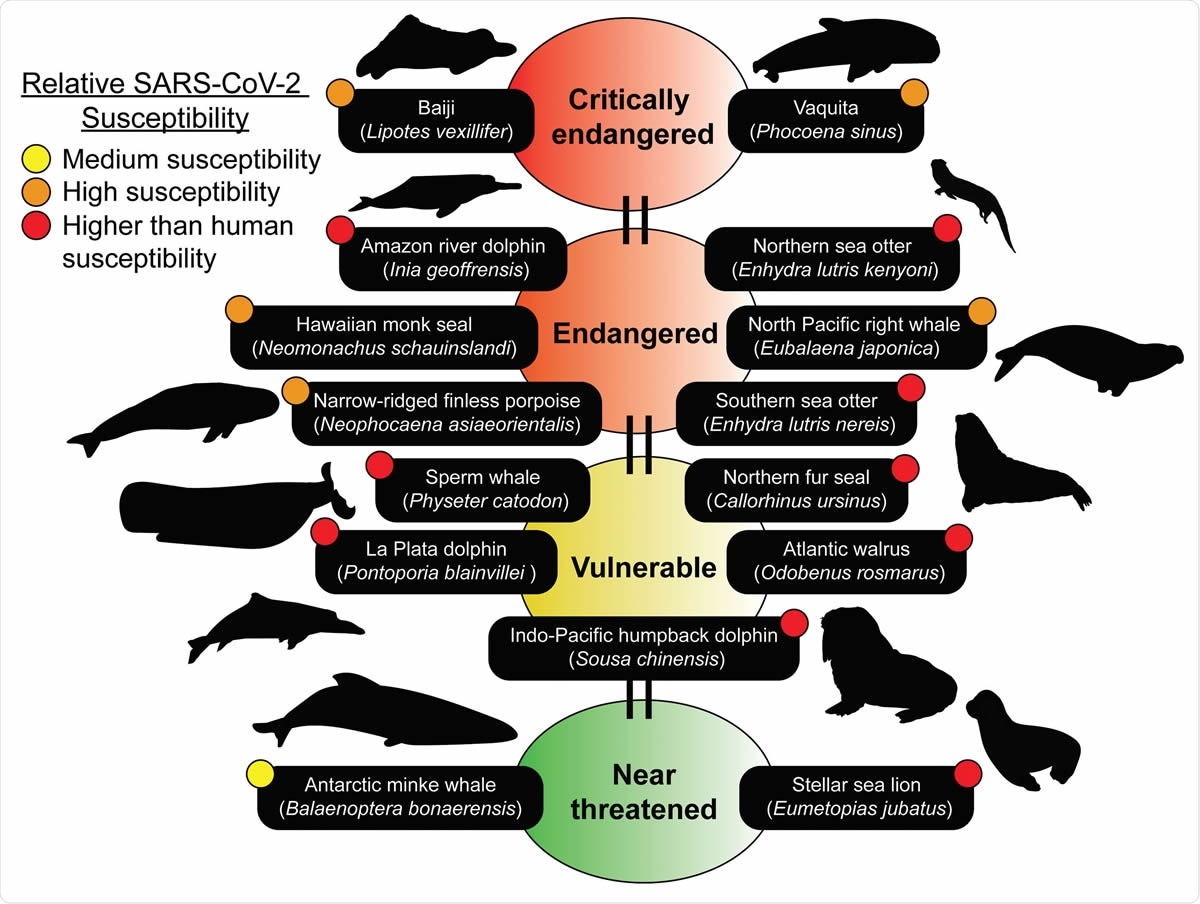

2. Marine mammal species predicted to be susceptible belong to the IUCN Red list. Many of the species predicted to be susceptible are members of the IUCN Red list of Threatened Species (https://www.iucnredlist.org). The IUCN Red list is an indicator of the world’s biodiversity and provides the most comprehensive data on the global conservation status of a species. 15 susceptible species ranging from medium to higher than human predicted susceptibilities can be identified on the IUCN Red list. Conservation statuses updated as of July 25th, 2020 were used. Silhouettes of species were drawn or obtained from PhyloPic (http://phylopic.org

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Patients with COVID-19 shed the virus in their urine and stool

Although SARS-CoV-2 is primarily a respiratory illness, reports have recently pointed to multi-organ infection, including the gastrointestinal tract. Researchers have also shown that patients with COVID-19 shed viable SARS-CoV-2 in their urine and stool and that the virus can be been detected in untreated wastewater in many countries, including Italy, Spain, France, and Australia.

“The absence or failure of a wastewater treatment plant can lead to sewage being another form of transmission that affects both humans and susceptible species,” write Dellaire and team.

The researchers say many types of marine mammals that are found close to contaminated natural water systems will be exposed to SARS-CoV-2 and that it is vital to identify which animals are most at risk.

Predicting the susceptibility of marine mammals

Now, Dellaire and colleagues have examined all publicly available data on the sequenced genomes of marine mammals and used a modeling approach to predict their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Amazon River Dolphin. Image Credit: COULANGES / Shutterstock

The team reports that most species of cetacean (18 of 21) are more susceptible than humans. Since many of the species are social such as the beluga whale and bottlenose dolphin, they are especially vulnerable to intraspecies transmission.

The majority of seal species (8 of 9) were also highly susceptible to infection. The one exception was the California sea lion, owing to a mutation in the animal’s angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to infect host cells.

Of all the mammalian species analyzed, the Atlantic Walrus had the ACE2 with the most significant binding affinity for the virus. Otters were also highly susceptible to infection.

Many of the vulnerable species are already at risk

More than half of the species that were identified as being highly susceptible to infection are already categorized as “near threatened,” “vulnerable,” “endangered,” or “critically endangered.”

“If these organisms are infected by SARS-CoV-2, their already dwindling population numbers will be even more at risk,” says the team.

In addition, geo-mapping studies showed how poor wastewater management in Alaska might further increase the risk to marine mammals.

Since Alaska is home to many well-documented marine populations, the team analyzed this information together with data available on wastewater treatment plants across the state.

Municipalities in the southern and northern shores primarily used secondary treatment, which has previously been shown to remove most traces of SARS-CoV-2.

However, the western shores primarily rely on lagoon treatment, a primary type of treatment that is less effective at removing infectious viral particles. Three species of seal are found along these shores, and the researchers say it will be important to gather data on their ACE2 receptor sequence to predict the potential risk to these populations accurately.

The team also identified some high-risk locations that use lagoon treatments on southern shores. These included Cold Bay in Naknek, which is home to highly susceptible sea otter species and Bristol Bay, where endangered Beluga whales are found.

Beluga whale. Image Credit: Kirill Skorobogatko / Shutterstock

“Efforts to mitigate and carefully assess the impact of the wastewater effluent discharged only after primary treatment into these marine mammal habitats will be important for protecting these species,” write the researchers.

“We must act with foresight to protect marine mammal species”

Dellaire and colleagues say it will be key to assess and appropriate wastewater treatment to reduce the impact of sewage-based transmission in natural water systems and those high risk areas should be particularly careful regarding how wastewater is managed and treated.

“At this point in the pandemic, the available evidence indicates that wastewater is an important vector for SARS-CoV-2 transmission for humans and susceptible wildlife,” they write. “Given the proximity of marine animals to high-risk environments where viral spill over is likely, we must act with foresight to protect marine mammal species predicted to be at-risk and mitigate the environmental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Related study

The Dalhousie research echoes the finding of another recent preprint research paper by scientists in the United Kingdom and Poland, and published on the preprint server medRxiv* in June 2020, that described the presence of stable SARS-CoV-2 in water for up to 25 days. The researchers pointed out that cetaceans, especially whales, are known to express ACE2 receptors with high similarity levels to humans, which means they can be vulnerable to the infection. The researchers estimate that a medium-sized whale could receive 5.65 million copies of the virus every second.

Study authors concluded, “The analysis suggests that public interactions with rivers and coastal waters following wastewater spills should be minimized to reduce the risk of infection.” The main risk is human-to-human spread, but it could also allow the virus to infect new animal species and, in turn, result in a future re-entry of the virus into the human population.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Source:

Journal references: