A thought-provoking new study by researchers in the Netherlands confirms the hypothesis that for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, higher age is associated with increased viral loads. This could have implications for non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) and mitigatory strategies for managing the pandemic, like school closures, as well as for testing strategies.

The beginning of the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic saw the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) shooting to prominence as the gold standard for diagnosing this infection. This test is mostly used to deliver a positive/negative result, but can also be used to estimate viral load in the tested sample if the cycle threshold (Ct), or crossing point (Cp) is examined.

In most cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection, viral load kinetics first show a steep increase in viral load, before symptoms develop, followed by a slow fall. Viral cultures are successful only if the sample has a low Ct value (below 27) while when it is above 35, the virus is hardly cultivable, indicating a low risk of spread. However, it is difficult to directly compare viral loads in different populations, due to the use of varying assays and methods, which impact the Ct.

The current study therefore focused on the Ct in all samples from a routine sampling population, all tested at one Dutch regional laboratory. The aim was to find a differential between various patient groups, including hospitalized, GP, nursing home, healthcare workers (HCWs), and patients tested in public health test centers, as well as between age groups, with respect to the viral load and the period over which symptoms existed.

The study included over 270,000 patients, using only the first result. If there were multiple positive results, the first was used, whether positive or negative. About 9% were positive. In the first wave, over a quarter of tests were performed for hospital patients, but this group made up only less than 1% in the second wave, with over 80% being from the Dutch Public Health testing system.

Population-distinct patterns

Higher Ct values (lower viral loads) in respiratory samples were associated with samples obtained in the first wave. However, in this wave, Ct values were lower in Public Health patients than in GP patients, in non-hospitalized patients, and HCWs in nursing homes. With the onset of the second wave, nursing home residents and GP patients showed lower Ct values.

Age and gender matter

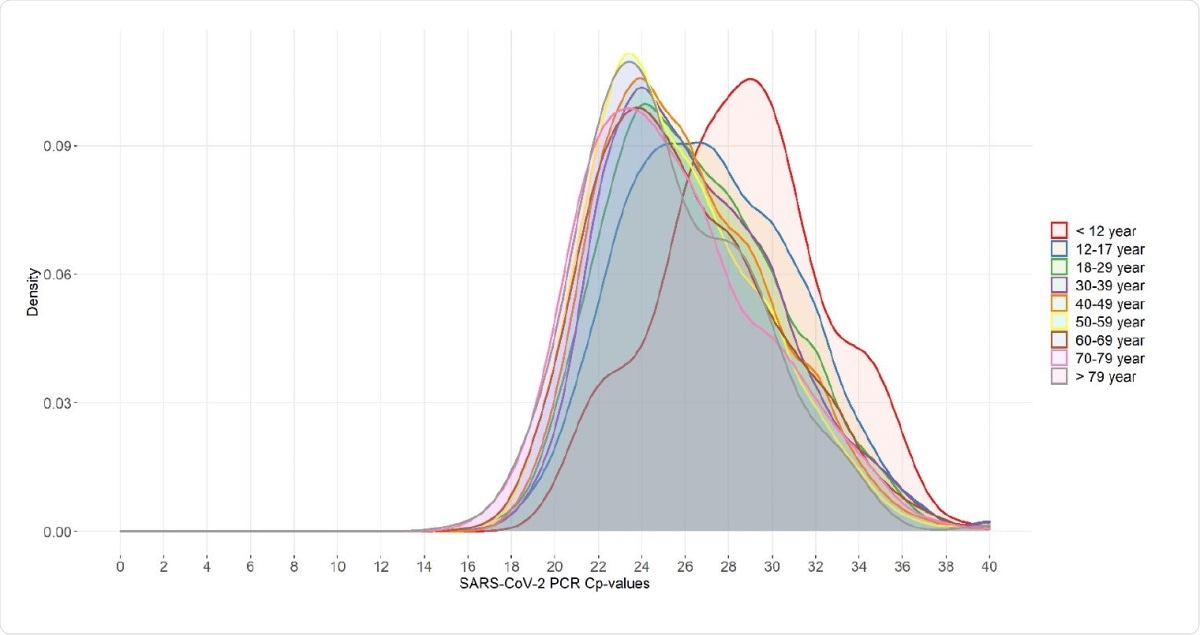

When stratified by age into the following categories, namely, 0-12 years, 12-17 years, 18-29 years, 30-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, 70-79 years, and over 79 years, the study demonstrates that advancing age is linked to a higher percentage of positives and higher viral loads. The younger patients were much more likely to have Ct values above 30.

About a third of children below 12 had Ct above 30 but only half of other patients. Median Ct values were 4-fold higher in the youngest group compared to the oldest, which corresponds to a 16-fold reduction in viral load.

When both the time of symptom onset and testing was known, increasing age was found to be related to lower Ct values, at any interval between symptom onset and testing. This was observed despite the fact that viral load increased with an increase in this interval.

Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 PCR Cp-values within different age groups (n=18.290) Each color corresponds to one specific age group that was routinely tested in the period January 1-December 1. For each group the frequency of reported Cp-values was used to calculate a density score of which the area under the curve sums to 1.

What are the implications?

In this earliest study of viral load distribution in a wide range of patients, it is clear that viral load is always highest in older patients, independent of sex or of symptom onset. Again, the population tested for this infection was different in the first and second waves. And thirdly, samples in the second wave had a higher median viral load.

The reason for the change in tested populations is the shift in testing policy, which focused on hospitalized patients in the first wave, but shifted to more general testing as capacity improved, during the second wave.

The finding of low viral loads in younger patients is not in agreement with earlier studies, showing the unique importance of this study which used data from over 2,600 patients below the age of 20, and around 240 below 12. However, they offer several disclaimers. For one, the difficulty of performing nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal sampling painlessly in children may have led to a higher percentage of nasal or mid-turbinate samples, vitiating the results.

This aspect needs to be thoroughly investigated, as earlier studies yielded conflicting findings as to whether such samples have a reduced viral load. Secondly, most of the patients in the younger age group were old enough to tolerate the procedure.

Explanations such as a higher testing threshold for children or restricted testing do not appear to hold water, since the increase in viral loads with age holds steady over the one year of the study. Instead, it may be important to study the distribution and expression of the host cell receptor, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), in children, differential immunity in children, differences in the microbiome, and pre-existing coronavirus immunity.

Finally, the relative sensitivity of antigen testing vis-à-vis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing needs to be explored in relation to the results of this study. Since almost a third of children had Ct values above 30, antigen test sensitivity may well be lower in this group.

The study brings out the importance of using data from a broad spectrum of patients, in high numbers, from a single laboratory, so as to better uncover the actual shift in the tested patient population and viral load distribution. The low viral loads in children support the assertion that this age group does not play a key role in viral spread. More research will be needed to understand how this ties in with coughing and other epidemiological parameters that also affect transmission.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources